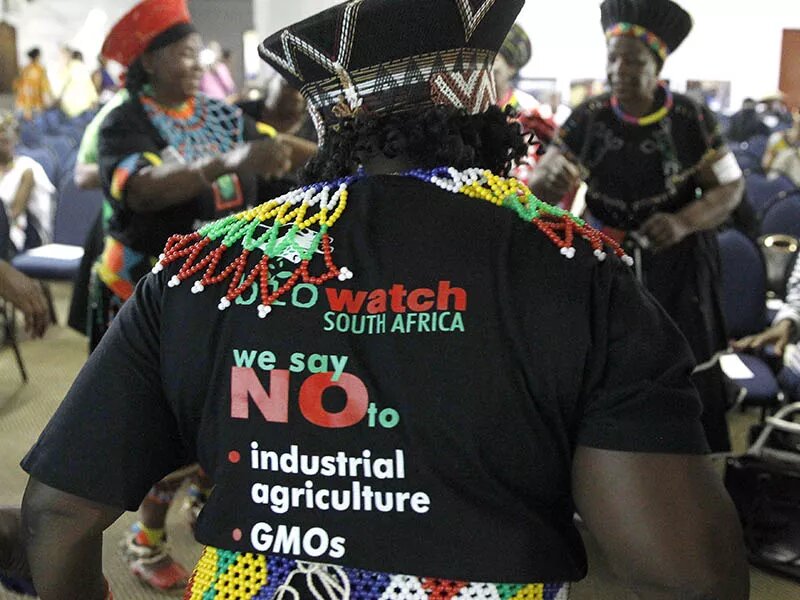

Despite claims of a vibrant democracy in South Africa, validated by one of the most progressive rights-based constitutions in the world, widespread hunger and malnutrition persist in the country, marked by child stunting, lack of dietary diversity, increased vulnerability to disease and an obesity epidemic. Recent statistics indicate that, in a population of approximately 55 million, 6.8 million people experienced hunger and 10.4 million people had inadequate access to food in 2017[1]. This indicates the failure of the South African government to adequately deal with the complex and multifaceted question of food security. This issue will undoubtedly become more significant as the climate crisis and climate instability impact more dramatically and unpredictably on the fabric of society. In this context, questions arise as to whether technological “fixes” in agriculture, such as genetically modified organisms (GMOs), could be the panacea for achieving food security in a context of the climate crisis.

Threats to Food Security

The food and agriculture sector is unique in that it is both a major contributor to the climate crisis and especially vulnerable to its impacts. Crop and livestock production will undoubtedly experience the most observable effects of climate instability. Increases in temperature (heat stress), evaporation and plant transpiration, and the frequency of extreme climatic events such as droughts, floods, heatwaves and cyclones will directly impact crop health and yields as well as livestock productivity. Agricultural pests and diseases will increase, soils will be eroded, and soil nutrients will be lost. Irrigation regimes will have to be more regulated or phased out altogether as groundwater and surface water sources become depleted or unreliable. Croplands, pasture and grazing lands will be more susceptible to bush encroachment and the spread of invasive alien plants. The increase in general biomass, due to higher levels of carbon absorption, will contribute to more devastating fires with direct and indirect effects on agricultural productivity. Employment opportunities and livelihoods associated with agriculture could decrease, thus intensifying food insecurity. A decline in the availability of food would lead to increases in food prices (price volatility) through the interplay of declining supply and growing demand, reliance on imported foods, and the increased cost of transportation due to shifts in production areas. Quantifying the actual impact that increased climate instability may have on agricultural production is difficult. Nonetheless, the recent drought and widespread fires in the Western Cape province – which led to a production decline of about 20 percent, along with the loss of approximately 30 000 jobs – may offer some foresight[2].

As more than 90 per cent of South Africa’s grain is rain-fed, any changes in rainfall patterns will impact directly on this sector, which includes some 2.3 million households. Some estimates indicate that “subsistence farmers could suffer revenue losses of up to 151% and commercial farmers 111% by 2080 due to the climate crisis”[3]. Climate-change modelling predicts a wide range of potential impacts on the average annual yield of dry-land crops, “although for most crops a decline is likely”[4]. In terms of maize, production in the North West and Free State provinces will decline substantially, while the Eastern Cape and southern KwaZulu-Natal may become new centres for maize production. Predictions on the possible impact on maize yields due to these spatial shifts range from a “national reduction of 25 per cent to an increase of 10 per cent”[5]. Other models predict possible decreases from 10 to 40 percent in the more distant future[6].

The Government’s Response

The 2012 National Development Plan (NDP) states that South Africa’s “capacity to respond to the climate crisis is compromised by factors such as social vulnerability and dispersed and poorly planned development, rather than inadequate climate-specific policy”[7]. Numerous legislative frameworks, policies and political statements do speak to the climate crisis adaptation and mitigation, but meaningful implementation of interventions remains poor.

A number of national, provincial and municipal programmes related to food security have been introduced, including:

- projects to support agricultural production, such as farmer settlements, community food production, one-household-one-hectare programmes, and tractor support

- poverty packages, which include seed and livestock handouts

- nutrition education and the promotion of staple crops containing increased levels of vitamin A, iron and zinc

- marketing support; loan schemes; small enterprise development; and the provision of infrastructure.

At a broader level, the government continues to prioritise funding for social programmes, such as school feeding schemes, general food assistance, emergency food relief, social grants, free health services, and public works programmes. Additional assistance may come in the form of agri-parks, agro-processing opportunities and land reform, as well as investment in research and technology to respond to production challenges such as those brought about by the impact of the climate crisis.

In the sphere of crop production more specifically, one of the main adaptation strategies is the promotion of “climate-smart agriculture” (CSA)[8]. This includes practices such as conservation agriculture and no-till agriculture. According to the national department of agriculture, forestry and fisheries (DAFF), CSA is more environmentally sustainable than current practices, reduces production risk, utilises fewer industrial inputs and therefore brings down the cost of production. All of this may be true – and the emphasis on soil conservation and fewer industrial inputs should be applauded – yet the promotion of CSA strategies does little to change the existing system or challenge the policies that led to the crisis in the climate–food system in the first place.

In terms of the role of GMOs, there is some ambiguity in government documents, although less so in practice. DAFF’s development plans speak of planting “different varieties of the same crop and maintaining seed varieties”[9] and the “adoption of appropriate technology, such as the development and use of drought resistant yellow maize varieties”[10]. Yet there is little real evidence of the former taking place, and the term “appropriate technology” appears to apply primarily to conventional industrial fixes, including GMOs.

Although the NDP notes public concern over the “genetic modification of food crops”,[11] this has not prevented the government from presiding over Africa’s only “mega-biotech country”,[12] with a total of 2.73 million hectares dedicated to the planting of GMO crops[13]. South Africa is also the first country to allow the genetic modification of its staple crop, namely maize. It is thus not surprising that state-driven CSA research is “aimed to produce low-cost drought tolerant conventional and transgenic (GM) hybrids”[14]. Despite the contradictory and ambiguous statements by various organs of the state on the issue of GMOs, there is little doubt that GMOs will play a significant role in government climate-change adaptation programmes, primarily in the form of public-private partnerships.

Arguments For and Against the Use Of GMOs

Despite state support of biotechnical solutions for the regeneration of rural economies, the debate for and against the use of GMOs to ensure food security remains a contentious one. Although the biotech industry acknowledges that GMOs are not a panacea, this has not prevented proponents of technological solutions from promoting GMOs as such. They argue that the risks are manageable and far outweighed by the need to “develop faster maturing and better yielding disease-resistant and drought-tolerant crop varieties to counter a changing climate”[15]. The polarised nature of this debate was recently reflected in an exchange on the Daily Maverick, one of South Africa’s foremost digital news platforms[16]. Columnist Ivo Vegter maintains that GMOs are “environmentally more sustainable than conventional crops”, lead to “improved yields”, “increased incomes”, and create more employment opportunities, and that nutritionally enhanced crops such as Golden Rice can help satisfy the nutritional needs of the poor in developing countries[17]. For proponents, the application of new biotechnologies – like GMOs – is the gateway to a technologically enhanced food-secure future, in which a broader spectrum of biotech solutions will increasingly be applied in food manufacturing and agriculture.

Despite state support of biotechnical solutions for the regeneration of rural economies, the debate for and against the use of GMOs to ensure food security remains a contentious one. Although the biotech industry acknowledges that GMOs are not a panacea, this has not prevented proponents of technological solutions from promoting GMOs as such. They argue that the risks are manageable and far outweighed by the need to “develop faster maturing and better yielding disease-resistant and drought-tolerant crop varieties to counter a changing climate”. The polarised nature of this debate was recently reflected in an exchange on the Daily Maverick, one of South Africa’s foremost digital news platforms. Columnist Ivo Vegter maintains that GMOs are “environmentally more sustainable than conventional crops”, lead to “improved yields”, “increased incomes”, and create more employment opportunities, and that nutritionally enhanced crops such as Golden Rice can help satisfy the nutritional needs of the poor in developing countries. For proponents, the application of new biotechnologies – like GMOs – is the gateway to a technologically enhanced food-secure future, in which a broader spectrum of biotech solutions will increasingly be applied in food manufacturing and agriculture.

As GMOs are still associated with a larger package of inputs that is only available to better resourced (generally male) farmers, rural communities will experience economic differentiation (disproportionally gendered), leading to the dispossession of land. Moreover, GMOs foster dependency on external inputs – often imported – rather than supporting localised low-input systems. Heirloom and local landrace crops are also at risk of contamination by GMO crops, again affecting the integrity of traditional varieties and impacting seed diversity. Critics also question the claims of increased yields and decreased chemical use with GMO crops and argue that GMOs are part of the conventional agricultural mindset that has contributed directly and indirectly to the climate crisis.

Alternative Approaches

Whether the existing food system can be sufficiently modified or transformed to become truly sustainable and climate-resilient remains an open question. Change is constrained by the vested interests of agri-business as well as the seductive power of a dominant developmental narrative that focuses exclusively on efficiency and productivity. Nonetheless, the biophysical contradictions inherent within industrial agriculture[18] and the emerging crisis resulting from the historical externalisation of costs by industrial agriculture has led to a groundswell of resistance. There are calls for a significant change to the system and even a complete paradigm shift that would alter the composition of the entire food system. Such a system would challenge existing power relationships by democratising the production and distribution of food and prioritising the interests of consumers and farmers and sustainable and ethical farming practices. It will also require rethinking agriculture’s place “in conceptions of development and modernity”[19].

What such an alternative system will look like and how it will function is highly contested. This is unsurprising as it involves conflicts over fundamental values and definitions in a web of general uncertainty as to what a climatically unstable future may actually entail. The emergence of a progressive farmer, farmworker and consumer movement that could push back against the dominant productivist agricultural system is still in its infancy in South Africa. Nonetheless, its key considerations would focus on more localised, biodiverse and less energy-intensive production based on agroecological principles and framed by the concept of food sovereignty. Skills would replace inputs: rather than one set of inputs replacing another, agricultural work would once more be valued, and there would be fewer mechanistic applications of bioscience. More effective soil and water management strategies, soil nutrient recycling and biocontrol would be introduced. A variety of agricultural enterprises would be encouraged, including mixed farming systems, agroforestry systems, food forests, and polycultures rather than monocultures. Such systems would be more adaptable to climate instability. In addition, appropriate technological innovations should be adopted and adapted to enhance the practice of sustainable farming – regardless of scale – and empower farmers rather than substituting for labour, skills and knowledge. Resilience in the face of the climate crisis would also include a rethinking and re-imagining of urban and peri-urban environments as holistic entities that produce food, generate energy from renewable sources, recycle waste, and so forth[20].

Concluding Comments

The inability of the South African state to meaningfully address the burning issue of food insecurity in the current context does not bode well for a future where the climate crisis and climate instability will magnify key problem areas in the entire food system. There is also little appetite for challenging the structure of an agri-food system that appears to be entrenching inequality and food exclusion. Furthermore, the historical bias towards agricultural production as the major strategy for food security remains and continues to shape the food security discourse. More pertinent questions about how food is accessed and consumed or how the broader food system functions are not on the table. Regardless of what its policy documents may state, the government’s focus continues to be framed by a productivist paradigm in which technological fixes such as GMOs and other inputs play a key role, especially in the context of climate instability.

What is required is a dynamic and flexible production system, one that integrates rather than disaggregates, includes rather than excludes, is farmer-centred rather than profit-centred and, most importantly, is sustainable and adaptable. This will ultimately involve the development and implementation of appropriate policies. Yet, as Lang and Heasman point out in Food Wars: The Global Battle for Mouths, Minds and Markets, the science of policy-making (and, in South Africa, policy implementation) is “inevitably political … is not precise: it is a product of politics and the (im)balance of forces. It is a matter of timing, mechanized by champions, vision and imagination – both private and popular”[21]. The time to activate new champions, vision and imagination is now.

[1] Stats SA. 2019. Towards Measuring the Extent of Food Security in South Africa. Report: 03-00-14. Stats SA. Pretoria. 6. Other estimates suggest that food access is a daily struggle for between 12 and 14 million people (see WWF. 2019. Agric-Food Systems: Facts and Figures. WWF. Cape Town. 4; South African Human Rights Commission. n.d. The Right to Access Nutritious Food in South Africa, 2016–2017. Research Brief).

[2] Palm, K. 2018. 30 000 Jobs Lost in WC Agriculture Due to Drought. EWN. https://ewn.co.za/2018/12/21/drought

[3] Republic of South Africa. Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF). 2014. Agricultural Policy Action Plan (APAP 2015–2019). DAFF. Pretoria. 72.

[4] United Nations University. 2016. Climate Change Effects on Irrigation Demand and Crop Yields in South Africa. Research Brief. No. 5.

[5] United Nations University. 2016. Climate Change Effects.

[6] Shultze, R. (ed.) n.d. Crops and Climate Change in South Africa 1: Cereal Crops. Thematic Booklet 4. DAFF. Pretoria. 1

[7] Republic of South Africa. National Planning Commission. 2012. National Development Plan 2030. Our Future Make It Work. Pretoria: 207. http://www.nationalplanningcommission.org.za/Pages/Downloads.aspx [9 August 2017].

[8] See DAFF. 2014. Agricultural Policy Action Plan (APAP 2015–2019). DAFF. Pretoria. 10.

[9] Republic of South Africa. DAFF. October 2012. Integrated Growth and Development Plan: 2012. DAFF. Pretoria: 45.

[10] Republic of South Africa. DAFF. 2014. APAP 2015–2019. 24.

[11] Republic of South Africa. National Planning Commission. 2011. National Development Plan 2030. Vision for 2030. Pretoria. RP270/2011. 72.

[12] AfricaBio. Agriculture. https://www.africabio.com/agriculture . [2 July 2019]

[13] Agaba, J. 2019. Why South Africa and Sudan Lead the Continent in GMO Crops. Cornell Alliance for Science https://allianceforscience.cornell.edu . [2 July 2019]

[14] ARC. 2016. Agricultural Research Council Celebrates Earth Day 2016, Remains Focused on Climate Smart Agricultural Research. Press Release.

[15] Agaba, J. 2019. Why South Africa and Sudan Lead the Continent in GMO Crops.

[16] Vegter, I. Strong GMO Opponents Unmoved by Facts. Daily Maverick. 11 June 2019; Genetically Modified Organisms: Let Science Prevail, Not Rhetoric. Daily Maverick. 28 June 2019; Why Nassim Taleb’s Anti-GMO Position is Nonsense. Daily Maverick. 11 June 2019; versus Black, V. Vegter: A Prisoner of Genetic Industry ‘Facts’. Daily Maverick. 18 June 2019.

[17] Vegter, I. Strong GMO Opponents Unmoved by Facts.

[18] See Weiss, T. 2010. The Accelerating Biophysical Contradictions of Industrial Capitalist Agriculture. Journal of Agrarian Change. 10(3): 315–341.

[19] Weiss, T. 2010. The Accelerating Biophysical Contradictions.

[20] Government policies to address urban food insecurity are generally weak, despite the rapid growth in urbanisation.

[21] Lang, T. and Heasman, M. 2007. Food Wars: The Global Battle for Mouths, Minds and Markets. London: Earthscan. 285.