Africa is a continent rich in land, fisheries, natural resources and biocultural diversity, all of which are critical assets for a well-functioning food system[2]. Despite this, Africans remain some of the most food-insecure citizens on the planet. The situation is most problematic in sub-Saharan Africa where the prevalence of chronic undernourishment appears to have risen from 20.8 to 22.7 percent in just over a year between 2015 and 2016[3]. Poignantly, Africa and Asia together bore the greatest share of all forms of malnutrition in the year 2018, accounting for more than nine out of ten of all stunted children, over nine out of ten of all wasted children, and nearly three-quarters of all overweight children worldwide[4].

Juxtaposed with the projected impacts of the climate crisis on food production, livelihoods and hunger, this grim picture becomes even more ominous. Unmitigated global heating could lead to a permanent increase in the variability of agricultural yields, excessive food price volatility, and a perpetual disruption to livelihoods, presenting many poor countries and communities with potentially overwhelming food-security challenges.

Impacts of The climate crisis on Africa’s Food System

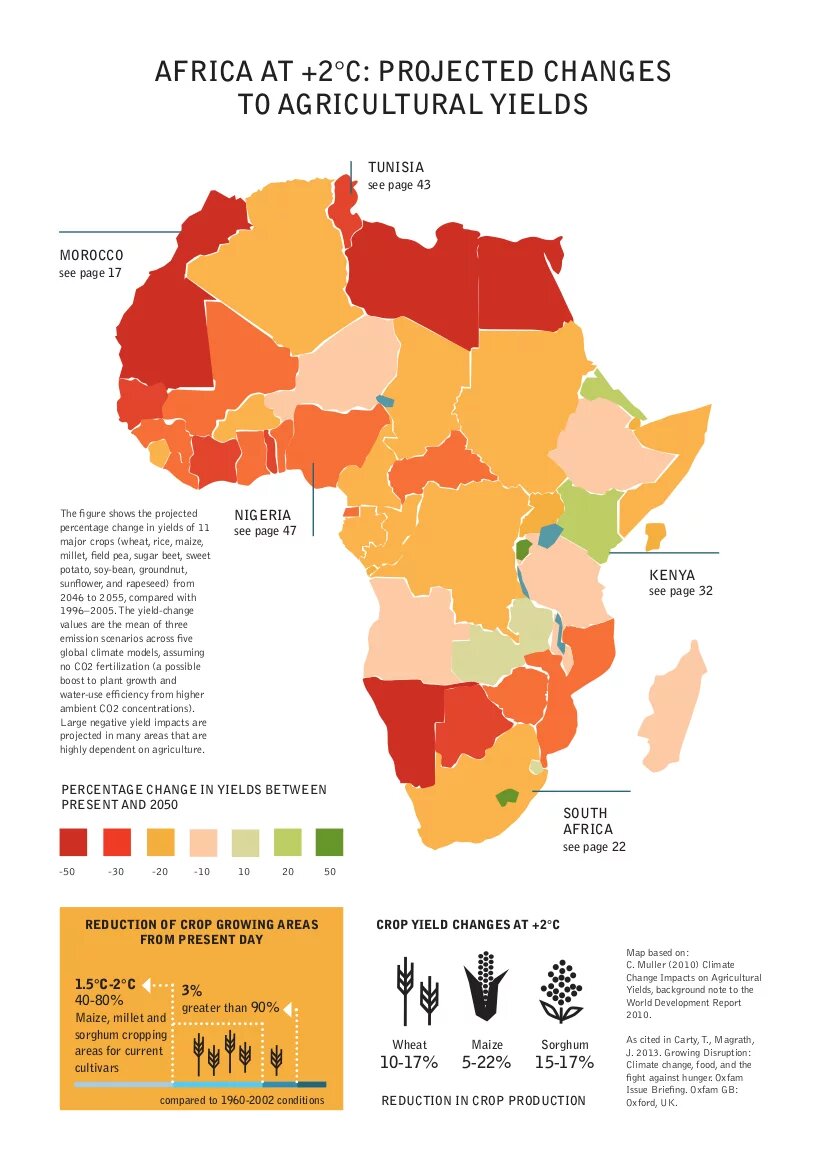

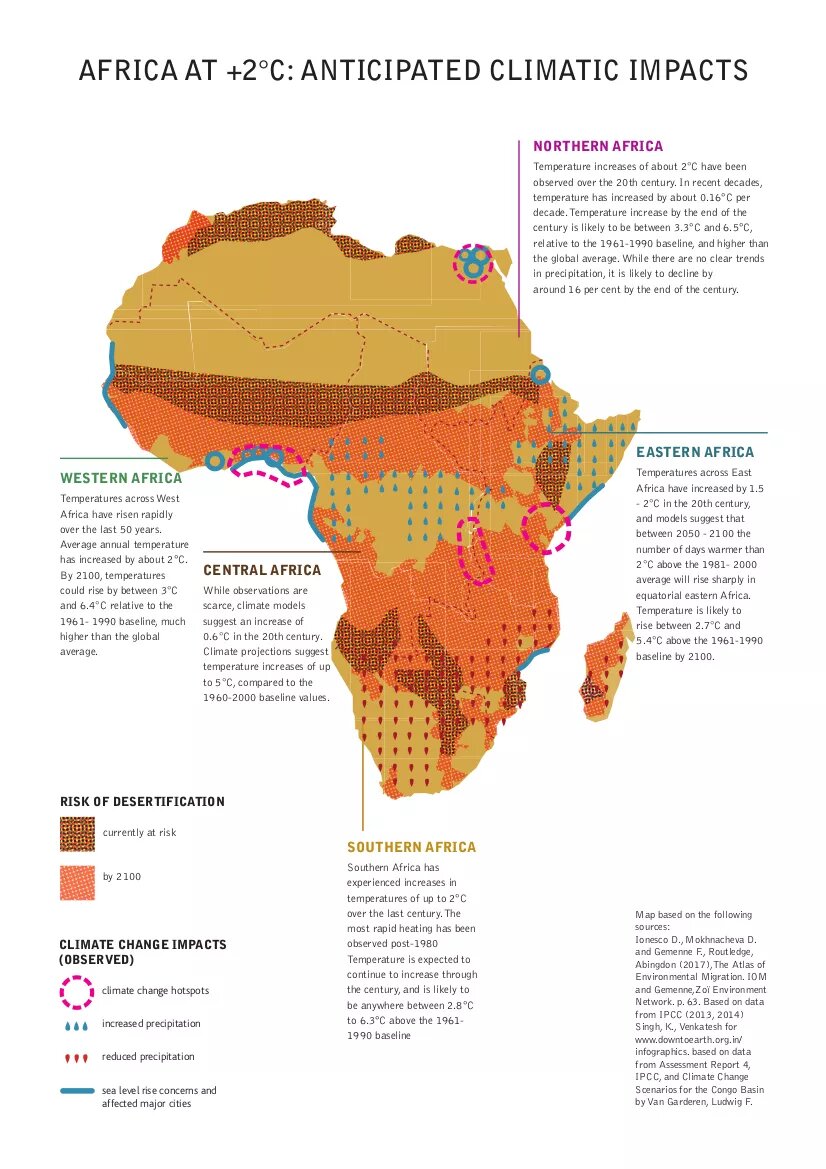

Warming trends are already evident on the continent and it is reported that Africa’s mean annual temperature change will likely exceed +2℃ of 2000 levels by 2100[5]. Changes in precipitation patterns are also of concern in a warmer climate, as it is likely that heavy rainfall will increase and be produced by fewer, more intense events. This in turn will mean longer dry spells and a higher risk of floods. Even if rainfall remains constant, increased temperatures will amplify water stress, putting pressure on agricultural systems, especially in semiarid areas.

Generally speaking, such changes are likely to reduce the productivity of cereal and high-value perennial crops, while higher temperature increases could decrease yields by 20–30 percent by 2080[6] and, according to one estimate, even as high as 50 percent in Sudan and Senegal[7]. Maize-based systems in southern Africa are particularly vulnerable to the climate crisis, with yield losses for South Africa and Zimbabwe currently predicted in excess of 30 percent[8]. Pests, weeds, and diseases are expected to increase, along with their detrimental effects on crops and livestock.

Africa’s vulnerability to the climate crisis is largely due to agricultural systems that remain rain-fed and underdeveloped[9]. The majority of farmers are small-scale, with few financial resources, limited access to infrastructure, and disparate access to information. These agricultural systems are highly reliant on their environment and the farmers are dependent on farming for their livelihoods. At the same time, and because of this, the diversity and context specificity of their farming practices and the existence of generations of traditional knowledge offer elements of resilience in the face of the climate crisis. Overall, however, the combination of climatic and non-climatic drivers and stressors will exacerbate the vulnerability of Africa’s agricultural systems to the climate crisis.

Such predictions are substantiated by the degree to which the shifting seasons are already making it difficult for small- and large-scale farmers alike to remain productive. In South Africa, 2016 ushered in a three-year-long drought, the worst in 34 years, and, in the Western Cape province, the most severe drought within living memory, pushing food prices to unprecedented levels[10]. Droughts have devastated agriculture in Zimbabwe and Zambia over the same period. Together with Malawi, these countries have been most affected by the warming and drying trends of recent decades, suffering severe food shortages over recent years.

Pathways Towards Ensuring Food Security in a Changing Climate

As the climate crisis continues to take hold, we need to think about what transformative measures can be taken to shift African food systems to a trajectory where healthy and sustainable food is available to all citizens, even under the stress of a changing climate. We discuss some of these below.

Recognise the role of women in the food system

A 2016 FAO report suggests that, if women farmers had the same access to resources as men, the number of hungry people in the world could be reduced by up to 18 percent[11]. Women smallholder farmers make up nearly 50 percent of the sub-Saharan agricultural labour force but are often inadequately considered in national agricultural policies[12]. In general, women carry the brunt of food insecurity and malnutrition much more than men: although they prepare up to 90 percent of meals in households worldwide, they may be the first to eat less during difficult times. They are also especially vulnerable to the impacts of the climate crisis because they shoulder an enormous – but imprecisely recorded – burden of responsibility for subsistence agriculture, whose productivity will likely be adversely affected by the climate crisis and overexploited soil[13]. We need to recognise the violence, that poverty and injustice inflict on women every day.

Given that access to nutritious food is a necessary (albeit insufficient) condition for eradicating poverty, economic conditions must be transformed to ensure that mothers have available resources to feed their children and households and that the agri-food system can provide food that is wholesome, affordable and easily accessible. Governments could make a significant difference by eliminating discrimination against women and by ensuring that all policies, programmes and projects take account of the different roles and responsibilities of women and men in the food system and the constraints that women face in agriculture and rurality more broadly. Greater and more effective involvement of women and utilisation of their knowledge, skills and experience will advance sustainability and development goals on the continent.

Tackle the industrialisation of agriculture and the food system

A small number of large and transnational corporations now dominate Africa’s value chains in the agricultural, food and beverage sectors, as well as specific food commodity chains. Regrettably, this economic power has been accompanied by enormous political clout, such that effective protection policies and mechanisms have generally not been established.

Consequently, the corporate agribusiness sector has been able to influence food-system governance in its favour. This threatens many countries’ capacity to develop and realise their population’s right to food. Poor regulation has contributed to the marginalisation of indigenous agriculture and crops and resulted in an environment saturated with unhealthy, cheap, ultra-processed food products and sugary beverages.

The biodiversity that is so critical to adaptation and resilience is threatened by large-scale mono-cropping, pesticides and seed and crop standardisation utilised by industrial agriculture[14]. In particular, the promotion of genetically modified agriculture products has created a vertical integration between seed, pesticides and production to increase corporate profits. Eighty-five per cent of all plantings of transgenic crops are soybean, maize and cotton varieties that have been modified not “to feed the world or increase food quality” but to reduce input and labour costs in large-scale production systems[15]. Food security requires more than producing enough calories and more than just agricultural interventions: it requires the availability of and access to healthy, nourishing food. Much stronger economic policies (such as subsidies and taxes) and regulation are needed in the food value chains to make healthy foods cheaper and unhealthy foods more expensive.

The UN’s 2019 World Economic Situation and Prospects report[16] notes that many countries pursue policies and strategies for realising the right to food, including subsidies for the production of staple foods. It recognises that some of these strategies may not be economically viable or optimal for diversification and structural transformation, but does not rule out their use for strategic and defined purposes.

Ironically, the state of the agricultural sector is seldom the major factor when governments consider what support to give it. Identifying support strategies that are economically sustainable, let alone environmentally and politically appropriate, is a complex task. However, such policies must be locally appropriate and reflect the local farmers’ needs and the range of their knowledge and methods. Their skills are at the heart of the continent’s potential for resilience, and the loss of diversity associated with industrialised agriculture must be recognised as the threat it is.

Strengthen the right to food

The issues of endemic hunger and malnutrition in Africa in the face of the climate crisis demands a dedicated and committed resolve by international, regional and domestic actors. Legislative and constitutional provisions that guarantee the right to food for all, including secure access to land and water, can be established and implemented in developing countries.

The right to food, along with other economic, social and cultural rights, must take its proper place in politics, in human rights systems, and in people’s minds. Emphatically, the optimal use of the available human-rights monitoring systems requires mutually supportive action by local, national and international civil society organisations.

In recent years, national human rights institutions like the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) have significantly advanced the dialogue on the right to food. Networking and cooperation are necessary for strategy and efficiency but also for formal reasons. For example, institutions – like the SAHRC and other civil society organisations – that have a consultative status with the Economic and Social Council of the United Nations can submit parallel reports to the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. They can also accredit grassroots activists who wish to submit information to the Committee concerning their government’s human rights record.

Acknowledgement of the right to food means that governments have to keep the promises they have made to move towards sustainable development and reduce poverty. In this context, human rights defenders should acknowledge that food security in a +2℃ world is ultimately a political issue.

Mobilise for climate action that strengthens governance capabilities and tackles hunger

Shifting the power of vested interests in the business-as-usual economy will require broad-based movements. To achieve the scale of mobilisation needed, the fight for a low-carbon future must be embedded in struggles for rights and equality. This means a pro-poor low-carbon agenda in Africa that does not just target the climate crisis but tackles inequality and hunger, too.

Agriculture is not explicitly mentioned in the ground-breaking 2016 Paris Agreement to address the climate crisis, despite efforts to include it. This is a cause of concern for many African countries, given the essential role that agriculture must play in the socio-economic development of the continent. All the same, Africa has generally welcomed the Paris Agreement because it is the first time that food security has appeared in a global climate change accord or agreement. At COP24, which took place in December 2018 in Katowice, Poland, Africa’s common position was for adaptation to be on par with mitigation, and the majority of African countries submitted their Nationally Determined Contributions to the global reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. These also project the national costs of both adaptation and mitigation. By and large, Africa’s adaptation efforts will require significant non-domestic conditional finance if they are to be implemented[17].

An African-led response to the impact of the climate crisis on the agriculture sector is provided by the 2014 Malabo Declaration on Accelerated Agricultural Growth and Transformation for Shared Prosperity and Improved Livelihoods. The Malabo Declaration is emphatic about the need to build the resilience of Africa’s agricultural sector – including livelihoods and production systems – to climate variability and other related risks. Verging on a policy of food sovereignty, it envisages the benefits of a higher level of regional integration and rational use of the opportunities offered by global markets.

The Malabo Implementation Strategy and Roadmap (IS&R) defines four thematic areas of priority action, each aiming to transform agriculture in the context of sustained inclusive growth[18]. In light of the strong corporate presence in the sector, the IS&R’s particular attention to African farmers’ capacities is encouraging. In another step in the right direction, its systemic capacity-strengthening objectives provide a credible framework for dealing with key stakeholders and their relations to economic policies. The Malabo Declaration envisions that, by the year 2025, at least 30 percent of African farm, pastoral, and fisher households will be resilient to climate- and weather-related risks. Unfortunately, of the 47 member states that reported progress in implementing the Declaration, less than 50 percent are on track to achieve this commitment[19]. This again indicates the imperative to elevate agriculture’s place on the political agenda.

Strengthening the implementation of the Malabo political programme as well as meeting the adaptation and resilience demands of global climate-change negotiations will require tackling key barriers to adaptation. These include:[20]

- inadequate infrastructure and finance that prevent the use of cutting-edge equipment in meteorological departments, which means that decision-makers do not have enough appropriate data and information on climate variability and change, as well as their impacts

- weak governance structures and institutions coupled with a lack of human resources and capacity, resulting in poor coordination among organisations and departments involved in adaptation to the climate crisis, as well as a breakdown in, or even a complete lack of, communication of climate information to farmers

- at the household level, there are financial barriers that hinder adaptation, and also barriers to growing drought-tolerant crops, such as lack of acceptance, availability, and ready markets, which in turn are linked to sociocultural barriers, as people maintain their preferences for existing staples

Both civil society and government interventions are required to address these barriers[21].

Conclusion

Ensuring food security in a +2℃ world requires simultaneous progress in poverty eradication, inequality reduction, guaranteed resource rights, the promotion of stable livelihoods, and gender equity. The challenges of global disparity and achieving the right to food for all in a highly variable climatic context are connected and cannot be solved separately.

Global heating adaptation and mitigation policies have to be integrated with the development agenda to fight poverty and hunger. The effects of the climate crisis will be widespread, but they may be less significant for those who have insurance or the ability to adjust their activities. Many African households depend directly on natural resources and agriculture and will not be able to move or otherwise buy their way out of problems. Thus, the continent will face particular problems as temperatures rise and floods and droughts impact agricultural production, water supplies, diseases and infrastructure, and the rural and urban poor will be the hardest hit.

[1] Parts of this article quote directly from: L. Pereira. 2017. Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture Across Africa, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science. Available at http://environmentalscience.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/97801993…. Indication is given in relevant paragraphs.

[2] Parts of this article quote directly from: L. Pereira. 2017. Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture Across Africa, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science. Available at http://environmentalscience.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/97801993…. Indication is given in relevant paragraphs.

[3] FAO, 2017, Regional Overview of Food Security and Nutrition in Africa 2017. The Food Security and Nutrition–Conflict Nexus: Building Resilience for Food Security, Nutrition and Peace, Accra: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available at http://www.fao.org/3/a-i7967e.pdf

[4] FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO, 2018, The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018. Building Climate Resilience for Food Security and Nutrition, Rome: FAO.

[5] Niang I., Ruppel O.C., Abdrabo M. et al, 2014, Africa. In Barros V.R., Field C.B., Dokken D.J., et al (Eds), Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1199–1265.

[6] Carty, T and Magrath, J. 2013. Growing Disruption: Climate change, food, and the fight against hunger. UK: Oxfam GB for Oxfam International.

[7] Cline, W., 2007, Global Warming and Agriculture: Impact Estimates by Country, Washington: Center for Global Development.

[8] Schlenker, W, and Lobell, D.B., 2010, Robust Negative Impacts of Climate Change; Lobell, D. B. et al, 2008, Prioritizing Climate Change Adaptation Needs for Food Security in 2030, Science 319 607–10. on African Agriculture, Environmental Research Letters 5 (2010) 014010 (8pp). This is quoted from Pereira. 2017. Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture Across Africa, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science. Available at http://environmentalscience.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/97801993….

[9] Material in this paragraph heavily relies on Pereira, L., 2017, Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture Across Africa, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science. Available at http://environmentalscience.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/97801993…

[10] Visser, W.P., 2018, A Perfect Storm: The Ramifications of Cape Town’s Drought Crisis, The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa 14(1), a567. Available at https://doi.org/10.4102/td.v14i1.567

[11] Howell, O., 2016, How Empowering Women Could End World Hunger, Global Citizen, 11 August. Available at https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/how-empowering-women-could-end…

[12] Jayne, T., Yeboah, F. and Henry, C., 2017, The Future of Work in African Agriculture: Trends and Drivers of Change. Research Department Working Paper No. 25, International Labour Organisation (ILO). Available at https://www.ilo.org/global/research/publications/working-papers/WCMS_62…

[13] Quoted from Pereira. 2017. Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture Across Africa, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science. Available at http://environmentalscience.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/97801993…

[14] Ibid.

[15] Fresco, L.O., 2003, Which Road Do We Take? Harnessing Genetic Resources and Making Use of Life Sciences: A New Contract for Sustainable Agriculture. In Towards Sustainable Agriculture for Developing Countries: Options from Life Sciences and Biotechnologies, EU Discussion Forum, Brussels, 30–31 January. Available at: http://www.fao.org/biotech/docs/fresco.pdf

[16] United Nations, 2019, World Economic Situation and Prospects 2019, New York: UN. Available at: https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wesp2019_en.pdf

[17] UN Economic Commission for Africa, 2018, From COP21 to COP24 in Katowice: Paris Agreement – Africa’s Realities and Aspirations, 11 October. Available at https://www.uneca.org/stories/cop21-cop24-katowice-paris-agreement-afri…

[18] African Union Commission, 2014, Malabo Declaration Implementation Strategy and Roadmap, 4. Available at https://www.resakss.org/node/5916

[19] African Union, 2018, Inaugural Biennial Report of the Commission on the Implementation of the June 2014 Malabo Declaration on Accelerated Agricultural Growth and Transformation for Shared Prosperity and Improved Livelihoods, Assembly Decision (Assembly/AU/2(XXIII)) of June 2014. Available at: https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/33005-doc-br_report_to_au_…

[20] The below is quoted from Pereira. 2017. Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture Across Africa, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science. Available at http://environmentalscience.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/97801993…

[21] See Antwi-Agyei, P., Dougill, A. J., and Stringer, L. C., 2014, Barriers to Climate Change Adaptation: Evidence from Northeast Ghana in the Context of a Systematic Literature Review, Climate and Development, 7(4), 297–309; Shackleton, S., et al, 2015, Why is Socially Just Climate Change Adaptation in Sub-Saharan Africa So Challenging? A Review of Barriers Identified from Empirical Cases. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change: Climate Change, 6(3), 321–344.