Like many other African nations, Kenya is looking at its agricultural sector as a base from which to grow the economy and boost foreign exchange earnings while attempting to reduce food insecurity. As one of the key pillars of its development agenda, known as the “Big Four Plan”, President Uhuru Kenyatta’s Jubilee government proposes to “modernise” the agricultural sector by supporting the growth of large-scale industrial food production. The country is therefore at an agricultural crossroads, where decisions taken now will impact the country’s food security and socio-ecological transformation for decades to come. As this article shows, however, such policy decisions may be based on a lack of appreciation of the current realities in the sector, a mis-diagnosis of the causes of the country’s food security problem, and an inadequate consideration of the effects of climate change.

The Status Quo: Kenya’s Agricultural Sector and Food Economy

Agriculture in Kenya is predominantly characterised by small-scale farming. Of the estimated 4.5 million farmers who cultivate approximately 90 percent of the country’s agricultural land,[1] about 3 million work in smallholdings, that is, roughly 75 percent of all farms.[2] Small-scale farmers use a mix of conventional and organic farming practices to produce over 70 percent of the gross value of marketed agricultural produce. Maize – which dominates the diet of sub-Saharan Africans – makes up more than half of small-holders’ household production in Kenya. Smallholders also cultivate sorghum, millet, cassava, potatoes, beans and vegetables.[3]

Eighty percent of the rural population relies on small-scale farming for their livelihood[4], where labour is provided disproportionately by women, although they have little ownership and control of the farms they work. Women provide 80 percent of Kenya’s farm labour and manage 40 percent of the country’s small-scale farms, yet only own roughly 1 percent of agricultural land and receive just 10 percent of the available credit.[5]

A History of Food Insecurity

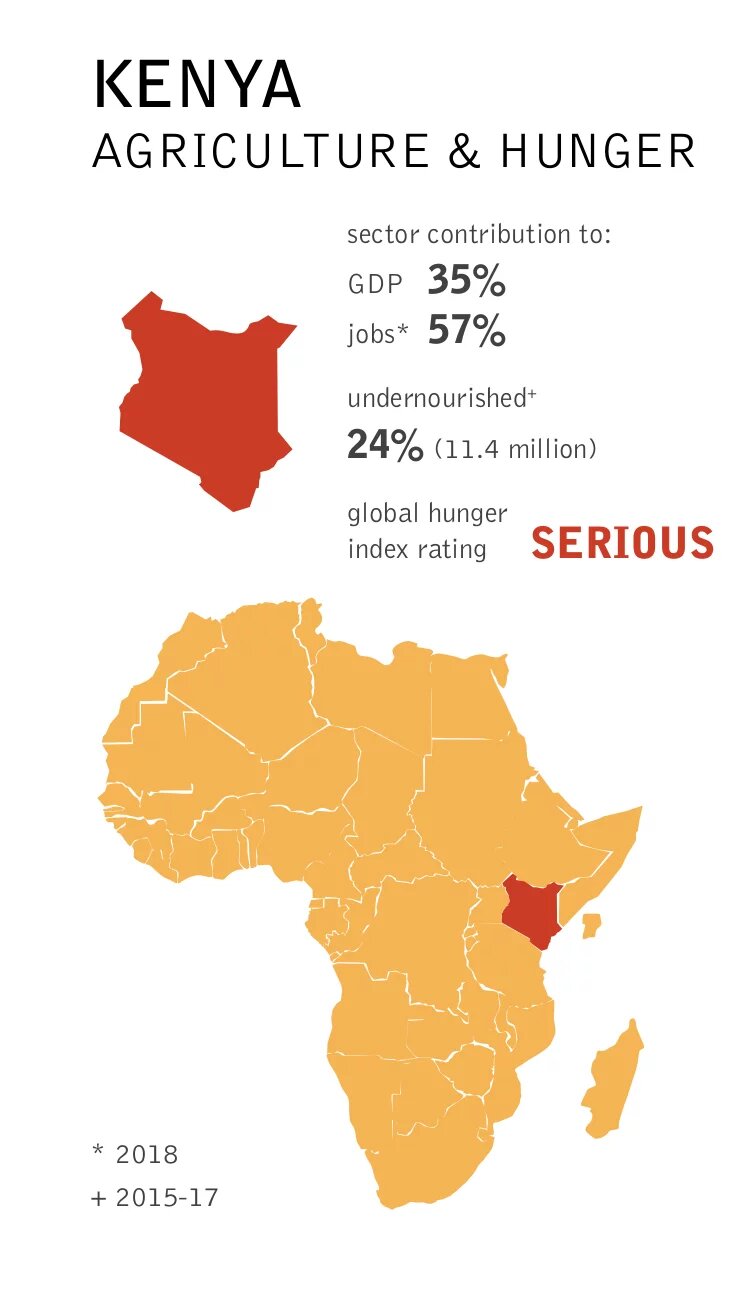

Despite the relatively large participation of households in the agricultural sector, systemic hunger and routine food crises have been a recurring feature since independence in 1963. The 2019 Global Hunger Index ranks Kenya as 86th of the 117 countries it measured for food security and classifies the country’s condition as “serious”.[6]

Over time, successive regimes have committed to address the matter. In 1972, Kenya signed the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, obligating the government to respect, protect and fulfil the realisation of the right to food. Article 43(1)c of the Constitution adopted in 2010 guarantees every person “the right to be free from hunger, and to have adequate food of acceptable quality”.

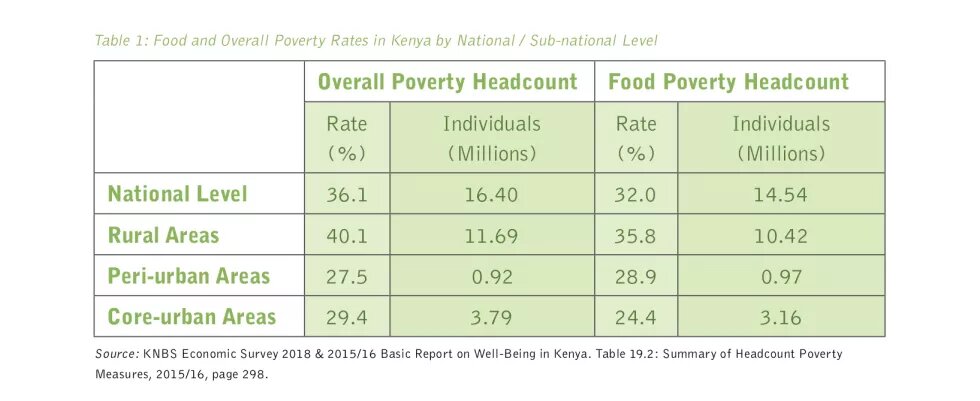

Nevertheless, an estimated 25 percent of the population still experiences chronic food insecurity, a category that ranges from people who cannot afford to eat enough food to those whose diets lack nutritional diversity and who are either undernourished or obese. An average smallholding family in Kenya generates a gross income of about USD2 527 per year. With an aver-age family size of approximately five per-sons, this amounts to about USD1.4 per day per person. With this little money, the family must buy food, clothes and other goods as well as pay for housing, education and health services. Kenya’s national food-poverty headcount rate is an alarming 32 percent of the population. This means 14.5 million Kenyans are classified as “individuals unable to consume the minimum daily calorific requirement of 2 250 kilocalories (Kcal) based on expenditures on food”. In rural areas, the food-poverty headcount rate stands at 35.8 percent, while it is also high in core urban areas, at 24.4 percent.[7]

Kenya’s overall poverty headcount rate at the national level is estimated at 36.1 percent of households. Hence, an estimated 16.4 million Kenyans have limited or diminished access to food at all price levels. Table 1 summarises the food and overall poverty rates in Kenya.

Kenya’s National Food and Nutrition Security Policy (2012) recognised that, primarily due to food not being affordable, most Kenyans subsist on diets based on staple crops, mainly maize, that lack nutritional diversity. This has had particularly devastating consequences on the nutrition of women and children. Twenty-six percent of children under age 5 are stunted, 4 per-cent are wasted, and 11 percent are under-weight. Nine percent of women aged 15–49 are thin or undernourished, while 33 per-cent are either overweight or obese.[8]

The impacts of climate change will worsen food insecurity. Kenya’s arid landscapes have been identified as some of the most vulnerable to higher temperatures and inconsistent rainfalls.[9] The effects of such changes on agriculture and food production are well documented: over the past two decades, four drought-related food short-ages have been declared national disasters. In a country heavily dependent on rain-fed agriculture, unreliable rainfall reduces food production for both subsistence and marketing, which increases the cost of food.

Increasingly dry, hot conditions and weather variability have exacerbated the devastation caused by the fall armyworm invasions.[10] In May 2017, a drought that affected 23 arid and semi-arid counties pushed the annual food-basket inflation rate 21.52 percent higher than the same month the previous year. In practice, this meant that basic food-stuffs – maize meal, rice, wheat flour, cooking oil, sugar, milk – became unaffordable for most households. Data from Kenya’s consumer price index shows that a house-hold with an average monthly spend of KES40 700 (about USD390) spends 45 per-cent of their income on food.[11]

Government’s Response

The government’s Big Four Plan expects to achieve food price reductions and 100 per-cent food and nutrition security by encouraging large-scale farming and boosting smallholder productivity, thereby increasing production. The ten-year Agricultural Sector Growth and Transformation Strategy (ASGTS) proposes to achieve these goals by improving small-scale farmers’ access to inputs, facilitating large-scale cultivation on more high-potential agriculture land, improving the productivity and profitability of large-scale producers, improving extension services and investing in research and digitisation.[12] These plans represent a significant departure from how farming systems have been established in the past. They are also not supported by a meaningful political commitment to implement change. For example, the 2019/20 national budget has not altered the adverse trends of low and declining allocations to the agriculture and food sector. As a proportion of total voted expenditure, the current allocation is 2.9 percent, down from 3.5 percent in 2016/17. Kenya continues to default on the commitment made in the Maputo Declaration to spend at least 10 percent of its budget on agriculture. Moreover, there is no evidence of incremental budgetary increases that would attest to the state’s constitutional obligation to progressively realise the right to food.

Misdiagnosis and False Solutions

The government’s approach suggests that Kenya’s food insecurity is a production problem. By contrast, an assessment of the situation and its history shows that it is a problem of physical and economic access as well as the unequal and inefficient distribution of food. Even as many people are unable to afford or access a proper diet, approximately 20–40 percent of food grown in Kenya is wasted because of a lack of storage facilities or poor infrastructure to access markets.

The proposed policy remedies do not take sufficient account of the current agricultural context, which includes declining biodiversity and increasing effects of climate change. The Big Four Plan promotes industrial agriculture and large-scale production of staples, which encourages monoculture. The plan has also justified political pres-sure to lift the ban on importing genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and to commercialise transgenic Bt Maize and Bt Cotton. GMOs and monocropping both reduce resilience to climate change by undermining natural biodiversity. Conversely, case studies from Zimbabwe[13], Nigeria, Tunisia, Morocco and Senegal[14] show that agroecological approaches to farming improve resilience because they mimic nature, increase the soil’s moisture retention, and make use of indigenous seeds and food crops that are better adapted to the local environment.

Monocultures also negatively impact soil quality. Like other parts of sub-Saharan Africa, Kenya suffers from soil constraints including acidity and toxicity, nutrient depletion, soil erosion and shallow soils.[15] Planting the same crop in the same place each year causes an imbalanced and inefficient uptake of nutrients from the soil, which reduces soil quality as well as creating greater crop vulnerability to attacks by pests or diseases.

In many parts of the country, poor soil structure and quality mean that farmers are forced to use expensive chemical fertilisers and pesticides to encourage plant growth and production. Although the ASGTS pro-poses to reduce the price of such inputs, their use will not only result in poorer soils but also fuel a vicious cycle of costly dependence for those who can least afford it. More-over, the effects of pesticides and fertilisers that make their way into groundwater or become airborne can be disastrous for the health of humans and other creatures, public health costs, and food production. Food and seed production relies on pollination, but 31 percent of all registered products are currently classified as toxic or very toxic to bees, which threatens the survival of bee populations and other pollinators and negatively affects food security. The Kenyan Pest Control Products Board has registered 699 products, of which 27 percent contain active ingredients that have been withdrawn from the European market.[16]

Alternatives

Appropriate solutions would begin with a correct diagnosis of the causes of food and nutrition insecurity in Kenya and a proper emphasis on the risks of climate change. They would include providing contextually appropriate and adequate extension services that specifically address the needs of small-scale farmers, and mechanisms for achieving food safety and promoting food diversity. Extension services are a critical mechanism for disseminating information and capacity building to small-scale farmers. To support Kenya’s economic growth and mitigate against the effects of climate change and changes in global food market trends, extension services should focus on post-harvest management, water harvesting and storage, nutritional diversity and agroecological systems of farming.

Despite rising food safety concerns in the country and the Big Four Plan’s prioritisation of environmental conservation as an economic enabler, the widespread use and regulation of chemical pesticides that have been withdrawn from the European market – the country’s primary source of import – is not addressed in national policies. One proposal to address the problem would be to levy environmental taxes on pesticides based on their toxicity to the environment (land, water, air), and to human and animal health. This would mobilise fiscal revenues while mitigating the negative effects associated with pesticide application and encouraging a shift towards environmentally and ecologically friendly agricultural systems.

Instead of promoting monocropping, Kenya’s agricultural policy should ensure the cultivation and availability of adequate quantities of diverse food commodities, such as non-maize cereals, fruits, vegetables and animal products. Government policies and investment should, therefore, go beyond large-scale production of staples towards supporting food diversity and indigenous food crops that are climate-resilient and nutritionally rich. This policy approach would encourage the increasing number of farmers around the country who have adopted a permaculture philosophy, as well as the many civil society actors that advocate agroecology as the scientific solution for sustainable, socially inclusive food systems, food sovereignty and the right to food. Grassroots farmer coalitions, such as the Biodiversity and Biosafety Association of Kenya and the Kenya Organic Agriculture Network, and organisations like the Laikipia Permaculture Centre are leading positive change and pushing for a shift in the way that farming is thought about and practised in the country.

In line with Article 118 of the Kenyan Constitution, which provides for public participation in making and implementing policy decisions, grassroots organisations have opportunities for civic engagement on matters relating to food security and agriculture. Currently, it is mostly stakeholders and civic right-to-food advocates who submit memoranda on proposals for the agricultural sector. To shift the scenario in agriculture and food security, all stakeholdrs in the food system, including non-farming communities and consumers, should take part in these processes of political engagement.

Conclusion

Kenya is at an agricultural crossroads that poses significant implications for the country’s food security and socio-ecological transformation. The government’s political roadmap, the Big Four Plan, has captured the attention of public discussions and penetrated policy documents. It advocates for industrial agriculture in service of the country’s GDP and export market. On the other hand, there is a growing consciousness among producers and consumers about the effects of climate change on food security and, therefore, the need to establish food systems that are resilient, nutritionally diverse and grown in a way that supports critical biodiversity and natural ecosystems.

Any truly transformative agenda that aims to provide a holistic and sustainable solution to food insecurity in Kenya in the context of climate change and biodiversity challenges also needs to address inherent gender and economic inequalities. Annual budget allocations and fiscal policies provide key opportunities to do this. The government needs to increase the current allocations to the agriculture and food sec-tors. Members of the public need to make the most of their right to participate in the legislative affairs of parliament. Every opportunity to engage in shaping the country’s policy framework and implementation is a critical opportunity to push for the creation of a fair and sustainable food system in Kenya.

[1] Kenya Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Irrigation. (2018). Agricultural Sector Transformation and Growth Strategy 2019–2029 (ASTGS), abridged version. Kenya: Government of Kenya. Pg 3.

[2] Rapsomanikis, G. (2015). The economic lives of smallholder farmers. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i5251e.pdf

[3] Rapsomanikis, G. (2015). The economic lives of smallholder farmers.

[4] Kenya National Bureau of Statistics does not define the land size of a smallholder farm. According to a report by the FAO, Kenyan smallholders farm on average 0.47 hectares. (Rapsomanikis 2015. The economic lives of small-holder farmers).

[5] Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. (2017). Women and Men in Kenya: Facts and Figures 2017. Available from: www.knbs.or.ke/download/women-men-kenya-facts-figures-2017

[6] Global Hunger Index 2019. Kenya. https://www.globalhungerindex.org/kenya.html

[7] Government of Kenya. (2011). National Food and Nutrition Security Policy. Available at: https://extranet.who.int/nutrition/gina/en/node/11501

[8] Kenya Ministry of Health. (2014). Kenya Demographic and Health Survey. Available: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr308/fr308.pdf

[9] Bassiounini Group. (2017) Rebuilding after El Nino. http://bassiounigroup.com/rebuilding-after-el-nino/

[10] Midega, C.A. et al. (2017). A Climate-Adapted Push-Pull System Effectively Controls Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera Frugiperda (J E Smith), in Maize in East Africa. Crop Protection 105: 10–15

[11] Kihanya, M. (2016). Kenyans are Survivors, They Spend Most on Bread and Butter. Available from: https://www.nation.co.ke/newsplex/food-shelter-clothing/2718262-3233540…

[12] Kenya Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Irrigation. (2018). ASTGS

[13] Wilson, J. (2019). Observations on Agroecology Post-Cyclone Idai. Available from https://routetofood.org/observa-tions-on-agroecology-post-cyclone-idai/

[14] Heinrich Böll Stiftung, Rabat. (2019). Femmes et agro-écologie en Afrique [Women and Agroecology in Africa]. Available from: https://ma.boell.org/fr/2018/11/29/femmes-et-agro-ecologie-en-afrique

[15] Zingore, S. et al. (2015). Soil Degradation in Sub-Saharan Africa and Crop Production Options for Soil Rehabilita-tion. Better Crops 99: 24–26.

[16] Route to Food Initiative (2019). Pesticides in Kenya: Why Our Health, Environment and Food Security Are at Stake. Available from: https://routetofood.org/pesticides-in-kenya-whats-at-stake/