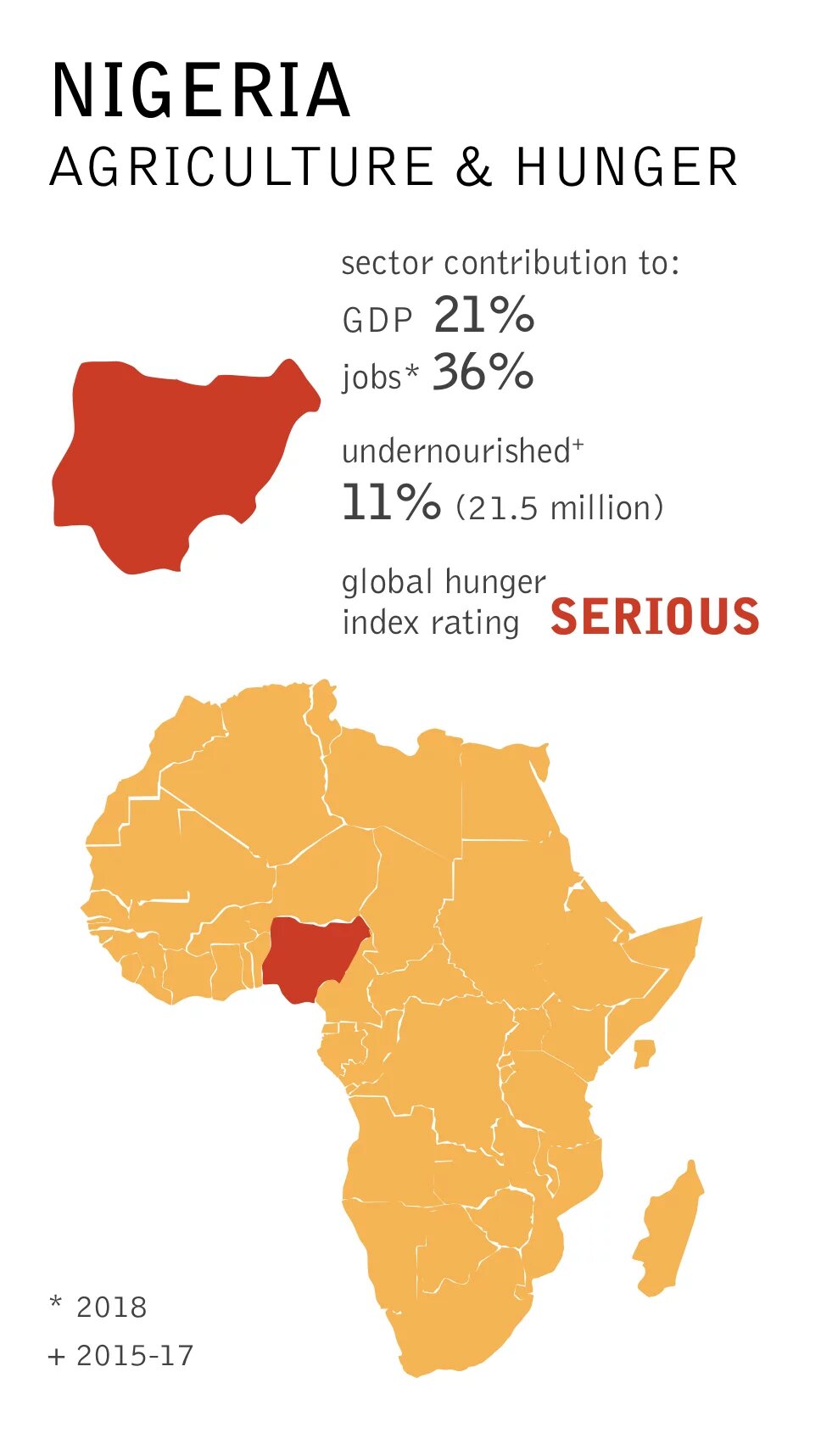

Small Scale Women Farmers Organisation in Nigeria (SWOFON) is a coalition of women farmers’ associations and groups across Nigeria. It was started with the support of ActionAid Nigeria in August 2012 to advocate for and support women farmers, especially those in rural areas, to spur rural village economic development and increase food production. It does this through deepening smallholder women farmers’ knowledge of and demand for their rights and the state’s duties, as well as serving as a vocal and visible pressure group on behalf of smallholder women farmers in Nigeria. SWOFON has state chapters across thirty-five states and the federal capital territory.

Osara is a rural community in Kogi State where farming is central to livelihood. The Osara community cooperatives are members of SWOFON Kogi State and linked to SWOFON at the national level. Perspectives spoke to Azubuike Nwokoye, the agricultural programme coordinator for ActionAid Nigeria, about the challenges faced by female farmers, how the climate crisis will affect them, and what ActionAid has been doing to support them.

What are some of the gender-based challenges faced by women farmers in the Osara community, and how do they hamper their productivity as farmers?

The challenges relate to all the required inputs and across the entire farming lifecycle. It begins with a lack of access and control over land, which limits women’s choice of crops. Most land farmed by Osara women is owned by their families or is rented. However, it is often the men in the families who decide which crops will be planted. Historically, men have always owned land due to the patriarchal culture of the community. Therefore, they allow women to only farm less profitable crops so that they can dominate the production of the more profitable ones. There have been instances where the men will refuse to renew a land-leasing contract with a woman farmer for the next planting season because the land seemed to have increased fertility.

Lack of access to simple labour-saving equipment is also an issue. Without tools such as hand tractors, harvesters and threshers, women are forced to use crude manual implements such as hoes, increasing their workload and impacting their health.

Because the men own the land, it is easy for them to access credit facilities using the landed property as collateral. The women find it difficult to access these loans and other credit facilities. Therefore, it limits their productivity as well as affecting their ability to purchase or hire labour-saving equipment for efficient farming. This has stifled growth and expansion of these smallholder women farmers and has resulted in high post-harvest losses and missed opportunities to add value to farm produce that could be sold for higher prices.

The poor rural road network causes increases in transportation costs, thereby limiting market access for these women farmers. Women are more vulnerable to the challenges of transportation than their male counterparts. For example, coupled with the difficulty in navigating the rough terrain of the roads, a woman farmer’s commute to the market is more likely to be subject to intimidation and sexual harassment. Due to these challenges, their husbands often restrict a lot of their movement to the market. Some women farmers also suffer from the lack of access to extension services, especially in Northern Nigeria, where the culture does not allow men to interact with married women, and almost all the extension workers in the region are men. Therefore, they are not able to provide services that would be beneficial to women farmers. This is the reason that part of our work is to advocate for increasing the number of female extension workers to interact with the women farmers.

The extra responsibilities of women as caregivers tend to expand existing challenges. Some women do not receive any further support from husbands who believe that their wives, being farmers, should also be able to handle every domestic responsibility.

The absence or inadequate provision of network services such as water reticulation, electricity and roads has similar effects. Without water points in their homes or fields, smallholder women farmers must trek kilometres every day and put both themselves and their families at risk of water-borne diseases. Without electricity, they cannot use simple labour-saving technologies such as grinding mills. Limited access to small irrigation facilities means that smallholder women farmers are dependent on rain-fed agriculture and cannot plant during the dry season.

Low productivity and profitability also result from limited access to inputs such as organic fertilisers, improved seeds and seedlings, as well as inadequate extension services. Without either the knowledge of farm practices that improve yields or the technology that enables them, production remains limited.

How has the climate crisis exacerbated these problems?

The climate crisis has already resulted in crop and livestock failures and threats to community food security. Rainfall patterns have become less predictable. Before, the first major rainfall of the year would signal the beginning of the planting season. Now, because rainfall patterns have changed, farmers who planted after the first major rains most times end up losing their crops as no more rainfall may be experienced during the period needed for the crops to survive. Flooding is another significant climate-change-induced challenge faced by Osara farmers. There have been times that, due to extreme rainfall, farms have been entirely swept away by floods.

What kind of support has ActionAid provided to the Osara women farmers, and how effective have these been in helping them grow resilient crops and increase their income?

To address the impacts of the climate crisis, climate-resilient agricultural practices were introduced to the women farmers. To cope with these climate-change challenges, we have been training the women on soil- and water-management practices like mulching to conserve soil moisture and reduce evaporation so that crops can survive the irregular rainfall patterns. This soil moisture-retention practice, coupled with the use of organic fertiliser, is helping to improve the fertility of the soil. Water harvesting from rainfall is another climate adaptation technique that we’ve employed. The women have also been taught to build special trenches around the farm to help mitigate the adverse effects of floods when they occur. They were also trained on correct spacing, compost-making, mixed cropping, combining both crops and livestock, home gardening (livelihoods diversification), organic control of pests and diseases, and alternatives to bush-burning and tree-cutting.

To tackle some of the other issues, we supported the women farmers’ ability to self-organise. While providing training on several climate-resilient farming practices, we realised that the women farmers’ voices were not adequately represented. Women were often excluded from participation in planning and development processes that could have been beneficial to them and their farms. And because the leadership of large farmers’ associations in Nigeria are mostly men (who are often big commercial farmers), the interests of smallholder women farmers are not well represented. This poor representation has been one of the reasons why these women continue to be vulnerable to the challenges we mentioned earlier. We decided to support the women farmers in this community to form cooperatives, which was done in partnership with local partners and provided training such as dynamic management and cooperative operations. This alliance of women farmers has grown to become a recognised network and movement for women farmers across Nigeria. They are also affiliated to other women’s groups in Nigeria and have a working structure and constitution. So far, this women-farmers’ group has a presence in about seven different states in Nigeria.

How has the intervention shifted political and community dynamics?

Their engagement as a group has given them a voice to engage collectively on their own issues. The results include increased access to land for individual women and increased access to cooperative lands from the community leaders.

ActionAid Nigeria has encouraged the women to share knowledge with their peers. Because of the benefits of the training, the smallholder women farmers’ productivity started improving and their peers that were not in cooperatives were attracted to join them. Right now, the women in this alliance have access to credit and land because they are more organised, they know how to advocate their issues and present them to the relevant local authorities. They have formed cooperatives in several other communities, which enables them to own land as a cooperative. They are also able to collectively access government benefit programmes like the anchor borrowers’ scheme, which was difficult to access as individual farmers.

How has the government responded to the women farmers organising themselves?

Government has responded through the provision of extension services, access to inputs and training to support their livelihoods. These women are now able to engage policymakers and make demands for what would be beneficial for their members. Such benefits could range from the provision of extension services to grants. The Osara community women have also been shortlisted to benefit from the government’s Small and Medium Enterprises Development Agency (SMEDAN) support for cassava processing under the One Local Government, One Product (OLOP).