In 2016, various allegations were made by opposition politicians and the media of a close and corrupt relationship between then President Jacob Zuma and the Gupta family from India (several of whom had had their applications to become South African citizens fast-tracked). Initial allegations that the Gupta family had “captured” the state centred specifically around rumours that they were instrumental in key decisions concerning the appointment of cabinet ministers, senior officials, and board members at state-owned enterprises. In June 2017, a hard drive containing some 200 000 emails was revealed by two whistle-blowers. The “GuptaLeaks” detailed extensive evidence of the Guptas’ influence over a wide range of state entities and officials. In 2018, a judicial commission of inquiry into allegations of state capture was established under the leadership of Deputy Chief Justice Raymond Zondo. It is still in progress at the time of writing.

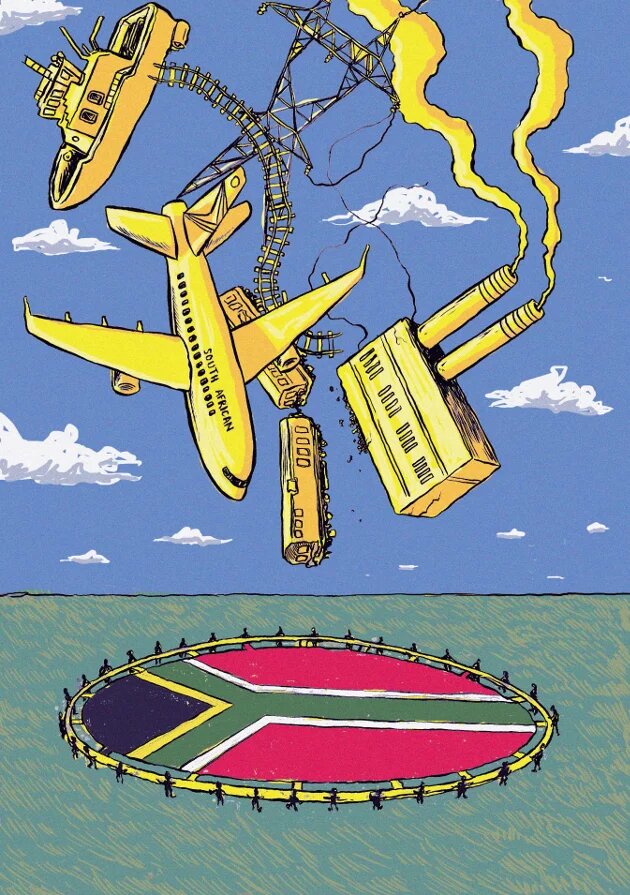

State capture has been at or near the top of the news agenda in South Africa for the past two years. A seemingly endless cast of characters has presented itself before the Zondo Commission to publicly confess their sins, or those of other people. An enormous web of corruption across almost every part of the state has been exposed, including a number of previously unknown schemes, such as those operated in the prisons by a company formerly known as Bosasa, led by CEO Gavin Watson, who has since been referred to as a “kingpin of bribes and corruption”1. Until these latter revelations, the Gupta family was the number one target of public anger in respect of state capture, but there are now several contenders for that dubious title. There appears to be no end to the tales of theft and malfeasance facilitated by handing over the authority for key decision-making and resource allocation to a small group of the politically well-connected.

For many years before these revelations, a sense of unease had been spreading in civil society about the apparently high levels of corruption, misuse of public funds and even outright theft across the public sector. Reports by the auditor-general indicated rising levels of irregular expenditure, much of it attributable to procurement irregularities. Although there were clearly problems with governance and accountability around public-sector procurement, some of the criticism had a distinctly racial tone: “they” clearly could not be trusted to run the country properly, and “they” were more interested in enriching themselves than in acting for the public good.

The ensuing debate around corruption – and the establishment of focused anti-corruption civil society organisations – largely adopted a very particular and narrow analysis of the drivers of corruption, and thus its recommended remedies. This approach, based on an individualistic rational-choice framework, views corruption in the public sector (and at this point, the public sector was seen as the main site of the problem, with little attention paid to the role of corporate South Africa) as driven by self-interested and greedy individuals, motivated entirely by personal gain. In many respects (albeit often unintentionally), these narratives of greedy individuals supported the position that black South Africans were inherently unfit to govern, and gave rise to nostalgic fantasies of a pre-1994 corruption-free South Africa.

Defining State Capture

Although “state capture” has become a common term in public narratives of corruption and general maladministration in contemporary South Africa, its definition varies. In most cases, it provides a shorthand for the perceived general malaise in the ruling African National Congress (ANC) and a sell-out by a small elite.

In the work of the Public Affairs Research Institute (PARI), the term denotes a particular political project designed to divert resources – mostly from state-owned enterprises (SOEs) via their extensive procurement budgets – to a designated (relatively small) group of beneficiaries. This was effected by the creation of a “shadow state”, a network of strategically placed individuals in key locations of state resources (such as the SOEs) and power (such as the National Prosecuting Authority, the State Security Agency and national ministries) within the constitutional state, and the development of a symbiotic rent-seeking relationship between this shadow state and the constitutional state.

In this conceptualisation, the political nature of the state-capture project centres around a rhetorical commitment to radical economic transformation and an accompanying sentiment that current governance and regulatory institutions – although supposedly focused on transformation through programmes such as broad-based black economic empowerment and preferential public-sector procurement – are in fact an impediment to “real” economic transformation. The persistence of high levels of inequality in South Africa since 1994 and the very small number of substantial black-owned businesses could be cited as evidence of the failure of these programmes. In this version, legislated rules for public-sector procurement are both a barrier to a more equitable economy, and difficult to change, given the political power of the National Treasury. Thus, state capture becomes a necessary transformational political project to overcome (or work around) these barriers.

The National Treasury, which holds most of the authority in this legislation, has traditionally taken a very conservative approach to fiscal management, and would strongly resist any attempt to radically revise it. There is also a widely-held view in South Africa that it is some kind of “last bastion” against corruption and the theft of public resources (not least because of Jacob Zuma’s attempts to place persons who were approved by the Gupta family as minister and deputy minister of finance), and it thus holds considerable power in the national narrative as to what is considered good governance.

Of course this vision – that state capture is fundamentally directed to economic transformation and redress for the majority – is not what has transpired in reality. The outcomes have been profoundly anti-poor, in terms of both the beneficiaries (a very small group, many of whom are not black or South African) and the financial impact, which has greatly reduced the pool of public resources available for other pro-poor programmes. As a result, the idea that state capture could be motivated by sincere altruism is largely discredited.

State-led Transformation

But it is important to remember that this has not always been the case: a clear component of the ANC’s original policy for governing a post-apartheid South Africa was that control over every part of the state was a necessary precondition for the fundamental transformation of society and the economy. It was necessary because, up until that point, the state had been focused on exactly the opposite, and the senior civil service at that time was predominantly made up of white South Africans whose key responsibilities had been the enforcement of apartheid legislation. They could not be trusted to deliver the new transformation agenda without close control. This control would be exercised for the specific purpose of ensuring that state resources were diverted for a particular political purpose. This need for control over decision-making and resource allocation was the rationale behind the ANC policy of cadre deployment to state institutions – political appointees to ensure that bureaucrats carried out this programme and exercised the requisite bias.

This overt policy bias was not, in turn, something new in South Africa. Post-apartheid transformation was almost inevitably framed in opposition to the political and economic oppression of apartheid. Although most of us make sense of our present and imagine our future with reference to the past, the view of 1994 as a watershed – representing a definitive break with the past and the start of something fundamentally new – fails to take full account of temporal continuity and all the ways in which history conditions and limits the present.

Three key features of the post-1948 apartheid state in South Africa were the deployment of the “right” people to key state institutions to oversee the use of state resources for the “correct” purposes (i.e. the enforcement of grand apartheid); the diversion of significant state resources to support elite interests; and the existence of an organisation similar to a shadow state (the Afrikaner Broederbond), through which a relatively small group of people exercised “true” control over the constitutional state. A deeply political agenda informed the state’s views on how public resources should be directed and who should benefit from those resources; there was no neutrality in how those decisions were made. This went much further than simply excluding the black majority from the benefits of government spending in infrastructure, education and health. A number of companies – such as the predecessors of the current BHP Billiton, Sanlam and Absa Bank – were established with the specific purpose of countering the historical exclusion of Afrikaners from the non-agricultural economy. Job reservation in SOEs was the main tool for addressing unemployment and poverty among low-skilled poor whites, who were predominantly Afrikaners. Additionally, a large number of higher-skilled professions were reserved only for white South Africans. Land ownership was also deeply skewed in favour of white South Africans.

In recent years, there has been a growing undercurrent of discontent with the state’s inability to drive meaningful transformation, particularly economic transformation. PARI’s work has repeatedly highlighted the existence of a view that procurement regulation – the type of regulation that outsiders would label “good governance” – was undermining the ANC’s transformation agenda and, as a result, it was the responsibility of elected officials to set that right. A significant percentage of citizens strongly believe that the role of “their” government is to exercise the same bias on their behalf that the apartheid government exercised in favour of white South Africans, and which was the fundamental reason for the relatively high income-status of almost all white South Africans. After all, they reason, how can we be expected to compete with white-owned companies that have a 100-year advantage for government business if there is no overt bias? Few of these people would object to the political objective of diverting state-owned resources in the service of benefitting the historically disadvantaged and increasing their beneficial participation in the economy. A pro-poor version of state capture is, after all, meant to be at the heart of the ruling party’s transformation agenda. In these narratives, the main “problem” with the current version of state capture is not the idea of diverting state resources to benefit a particular group, but rather with the profile of the beneficiaries (a small elite rather than the broader population of black South Africans) and the knock-on detrimental effect on the poor.

One of the more popular responses to the current revelations around state capture is a growing call for a completely neutral civil service (which would include all officials employed by the state across all three spheres of government and in the state-owned enterprises), free of any political bias or influence; a group of people whose only motivation in making resource-allocation decisions would be operational efficiency. These proposals fail to understand that the allocation of scarce resources among competing ends (a fundamental decision that the state is required to make) is never neutral in its impact, although certain elite groups have successfully presented their particular interests as either neutral or analogous to the common good. Allocating resources to one end requires that they are not allocated to another.

On what basis should we make those decisions, if not a subjective assessment of who deserves to be prioritised? Surely, a post-apartheid South Africa that aims to be profoundly transformative in its actions requires a pro-poor version of “state capture”, where the state’s allocation of resources is profoundly biased in favour of social justice and economic equity.

Endnotes

1 Jeanette Chabalala, “State capture inquiry: Bosasa CEO emerges as ‘kingpin of bribes’, ‘corruption’”, News24, 17 January 2019. See: www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/state-capture-inquiry-bosasa-ceo-emerge….

Bosasa changed its name to African Global Operations (AGO) in June 2017. In February 2019 – after South African banks announced that they would no longer operate accounts for the company – African Global announced it was going into voluntary liquidation, along with all its subsidiaries. Less than a month later, the company approached the High Court in Johannesburg to have the liquidation decision overturned, claiming that they had received bad legal advice. On March 14, the court agreed and ruled that the liquidators be dismissed. The next day, the liquidators were granted leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA), thus suspending the High Court ruling. Pending the SCA outcome, criminal corruption proceedings against Bosasa executives have been postponed until July (www.news24.com).