March 2021 Household Affordability Index and Media Statement

We call on the Reserve Bank to monitor much more stringently inflationary increases on food, electricity and transport and their impact on low-income households and the broader economy; and act decisively when such increases threaten the affordability levels of low-income households and damage the economy.

Inflation impacts low-income families disproportionally.

Inflation affects different people differently. People who earn a lot, spend on a lot of things; people who earn a little, spend on fewer things. On low wages, families spend most of their money on food, electricity, and transport. If we want to understand how inflation impacts low-income families than we must look at inflation, specifically on food, electricity, and transport.

For the past, several years these three core goods and services have been experiencing very high levels of inflation; whilst general or overall inflation has been relatively subdued. Annual wage adjustments for low-paid workers and annual increases on social grants have been very low compared to the high inflation levels on food, electricity, and transport. This has meant that families are not able to afford this year, what they were able to afford last year because increases on wages and grants are lower than the increases on basic goods and services.

A good example is that of the Child Support Grant because almost all the money is spent on food. The annual increase which will come into effect in April is 2,2% or R10, taking the total grant value to R460 per child per month.

In comparison with the 2,2% increase, Statistics South Africa’s Consumer Price Index in February 2021 shows that inflation on Food & Non-alcoholic beverages is 5,2%[i] (headline inflation is 2,9%). The National Agricultural Marketing Council’s [NAMC] Food Price Monitor (February 2021), in January 2021, shows that inflation on their basic urban food basket is 9,8%.[ii] NAMC uses STATS South Africa’s data, and measures a sample basket, and is therefore a more accurate measure of inflation for low-income households. PMBEJD data off our Pietermaritzburg Household Affordability Index, annualised for March 2021, shows that inflation on the Pietermaritzburg Household Food Basket is 12,6%.[iii] The cost of this basket has increased by R406,46 over the past year, with the total cost of the basket costing R3627,45. The PMBEJD data only focuses on low-income families and is able to capture a truer reflection of inflation experienced by low-paid workers and people accessing social grants.

When we argue that annual wage adjustments for workers paid at the National Minimum Wage level and people accessing social grants are not enough, we do so from this framework of isolating inflation on these core goods and services which low-income families spend most of their money on.

There is a question here around the role of the Reserve Bank. The Reserve Bank has a mandate to keep inflation within the 3-6% band. This mandate appears to kick in sharply when wage levels are being negotiated. In these instances, the Reserve Bank calls out ‘unreasonable’ wage demands. The Reserve Bank however seems not to display this level of passion and consistency in intervening to keep the level of inflation on essential goods and services for low-income households down. For example, there appears to be no intervention from the Reserve Bank when Eskom decides to increase electricity tariffs by 15,63%, or when food prices rocket to above 10%, or when public transport taxi fares increase by 7% or even the 25% seen in Gauteng last year. The Reserve Banks apparent oversensitivity to higher than inflation wage demands but an almost complete disregard to inflation on the main expenditure items for low-income households is curious.

This interpretation of the Reserve Bank’s role and mandate seems to us to keep general inflation low which positively impacts employers (government and corporates) by giving legitimacy to reject demands for higher than inflation annual wage increments. Whilst protecting the employer, it is low paid workers who carry the burden of what could be termed an artificially low inflation rate, this rate bearing very little relation to the real inflation rate experienced by workers. It is off the backs of low paid workers that the general inflation rate is low because the core goods and services which increase well beyond inflation are given very low weightings in the CPI basket. Essentially by keeping general inflation low, low-paid workers subsidise higher income earners and bosses.

We therefore call on the Reserve Bank to monitor much more stringently inflationary increases on food, electricity and transport and their impact on low-income households and the broader economy; and act decisively when such increases threaten the affordability levels of low-income households and damage the economy.

Key data from the March 2021 Household Affordability Index

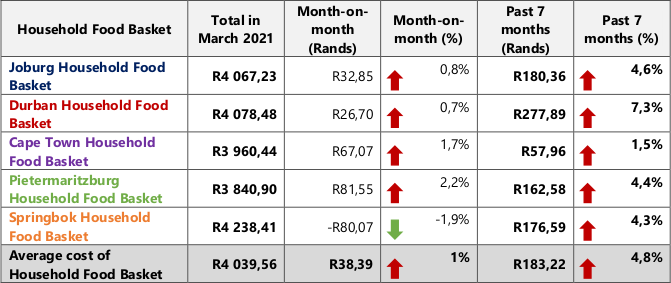

The March 2021 Household Affordability Index, which tracks food price data from 44 supermarkets and 30 butcheries, in Johannesburg (Soweto, Alexandra, Tembisa and Hillbrow), Durban (KwaMashu, Umlazi, Isipingo, Durban CBD and Mtubatuba), Cape Town (Khayelitsha, Gugulethu, Philippi, Delft and Dunoon), Pietermaritzburg and Springbok (in the Northern Cape), shows that:

- In March 2021: The average cost of the Household Food Basket is R4039,56.

- Month-on-month (between February 2021 and March 2021): The average cost of the Household Food Basket increased by R38,39 (1%).

- Over the past seven (7) months (between September 2020 [the first data release] and March 2021): The average cost of the Household Food Basket increased by R183,22 (4,8%), from R3856,34 in September 2020 to R4039,56 in March 2021.

Between February 2021 and March 2021, all Household Food Baskets, except Springbok increased. The average increase over the past seven months stands at 4,8% or R183,22 in March 2021. In comparison, the National Minimum Wage was increased by 4,5%, with a monthly Rand-value increase of R163,68 in March 2021. Pensioners will get a 1,6% increase or R30 in April 2021. Mothers raising children will get a 2,2% increase or R10 in April 2021. Food price hikes are outpacing increases in baseline wages and social grants. We expect that this upward trend in food prices is likely to continue.

Table 1: Summary of cost of Household Food Baskets for March 2021, month-on-month, and over the past 7 months.

The maximum National Minimum Wage in March 2021 was R3817,44.

In March 2021, the NMW was raised by 4,5%, or 93 cents extra an hour, R7,44 for an 8-hour day, and R163,68 for the 22-working day month. The higher NMW still falls far short of anything close to a living wage, and workers will continue to sacrifice nutrition and take on debt to cover wage shortfalls. Our March 2021 data shows a 34,8% shortfall in food on the NMW. This shortfall is almost too much to comprehend.

In April 2021, the new Old-Age Grant for a pensioner will be raised by 1,6%, or R30 extra a month to R1890. Pensioners have expressed dismay at the low increase. Pensioners say it is nowhere near enough and are extremely disappointed with the state. Pensioners are expecting 2021 to be an intolerably difficult year.

In April 2021, the new Child Support Grant for mothers caring for children will be raised by 2,2%, or R10 extra a month to R460. Our figures off the Basic Nutritional Food Basket show that the month-on month increase on the average cost to feed a child a basic nutritious diet per month increased by R12,24. The average cost in March 2021 rose to R722,99. This shows that even before the annual increment of R10 has come in, in April 2021, in March 2021 the cost to feed a child is above the future increment; it also shows that the future CSG of R460 is set 21% below the food poverty line (R585) and 36% below the average cost to feed a child (R722,99) on the March data. If you imagine what a 36% deficit might look like on your own child’s plate and the consequences thereof; this situation rolling out in millions of homes becomes almost too ghastly to contemplate.

It bears repeating that not ensuring that mothers are able to feed their children properly is a direct form of everyday violence against women and children. It is further a direct sabotaging of South Africa’s education outcomes, our health outcomes, our future social-political outcomes, our future economic outcomes; and any hope to reduce inequality, poverty, and unemployment in South Africa; or put us on a path to recovery. We are building a very fragile future on the bellies of millions of hungry children.

We are in now in a situation where South Africans are worse off than they were before March 2020. Jobs continue to be lost. People have less savings, and less money. Food is being taken out of children’s mouths. The prices of essential goods and services continue to rise. People will be poorer this year than they were last year. It is unlikely that this status quo will change and so we expect that the affordability crisis in households will deteriorate further.

When all our money is going to electricity, transport, and food; we must expect our economy to decline further. When the money we spend goes to big corporates whose business model is to bring in cheap imports instead of investing in local infrastructure to support local business and local jobs, with government support of this economic framework, we dig ourselves deeper into oblivion every day. There is nothing to suggest this will change. Talk of an economic recovery is meaningless, it is a lie.

Winter is coming, and the cold is likely to exacerbate misery and unhappiness and anger in a very large portion of our population. Being hungry, being cold, staying in the dark does not auger well for a people who are under enormous strain and who are increasingly conscious of where we come from and how poorly the state has done to delivery justice and transform our society and economy. The triggers, we have long predicted, where material conditions just become too intolerable and where one person, two people, three people start to say, “we cannot and will not continue to live under such conditions,” will start multiplying.

We can no longer pretend that our leaders do not know what is happening. They know. It seems to us that the myopic economic frameworks we have relied on since 1994 have reached their nadir. Despite this, it does not appear that the status quo will shift. Our structural inequities with our racism, our neoliberal economics, our land injustice, our apartheid geography, our apartheid wage regime, our unequal and in many cases abysmal education system, our fractured society, our shattered dreams, our daily misery will continue and worsen.

We feel that we have reached a critical moment in the life of South Africa. The decisions we make now will either lock us into poverty, inequity, civil strife, and violence for generations to come; or will provide a new path of justice, equity, economic and racial transformation, and a chance for us all to be fully human and live a dignified life.

The public mood seems to us to be shifting rapidly. It seems to us that much of our future rests in the decisions that will be taken by hungry men and women.

For information and media enquiries, contact: Mervyn Abrahams on 079 398 9384 and mervyn@pmbejd.org.za; or Julie Smith on 072 324 5043 and julie@pmbejd.org.za.

------

[i] STATSSA (2021). Consumer Price Index: February 2021. Statistics South Africa. Statistical Release P0141. Pretoria, South Africa. P7.

See link: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0141/P0141February2021.pdf

[ii] NAMC (2021). Food Price Monitor: February 2021 Issue. National Agricultural Marketing Council. Pretoria, South Africa. PI.

See link: http://www.namc.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Food-Price-Monitor-February-2021.pdf

[iii] PMBEJD (2021). Pietermaritzburg Household Affordability Index: March 2021. Pietermaritzburg Economic Justice & Dignity Group. Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. P2. See link: http://www.pmbejd.org.za