Mozambique has been battered by devastating cyclones and an armed insurgency. The backdrop to this is a state battling State Capture. This involves a coterie of corrupt politicians. However, at the centre of one of Africa’s biggest corruption scandals is a Swiss banking behemoth – Credit Suisse.

In 2016, 14 donors and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) stopped all lending to Mozambique. This followed the revelation of $2.2-billion in secret “tuna bond” loans undertaken by the Mozambican state from two banks – the Swiss bank Credit Suisse and VTB Capital, majority owned by the Russian state. The result was an economic crisis that saw the national currency plummet in value by 70% and the GDP growth rate fall from 6.7% to 3.8%.

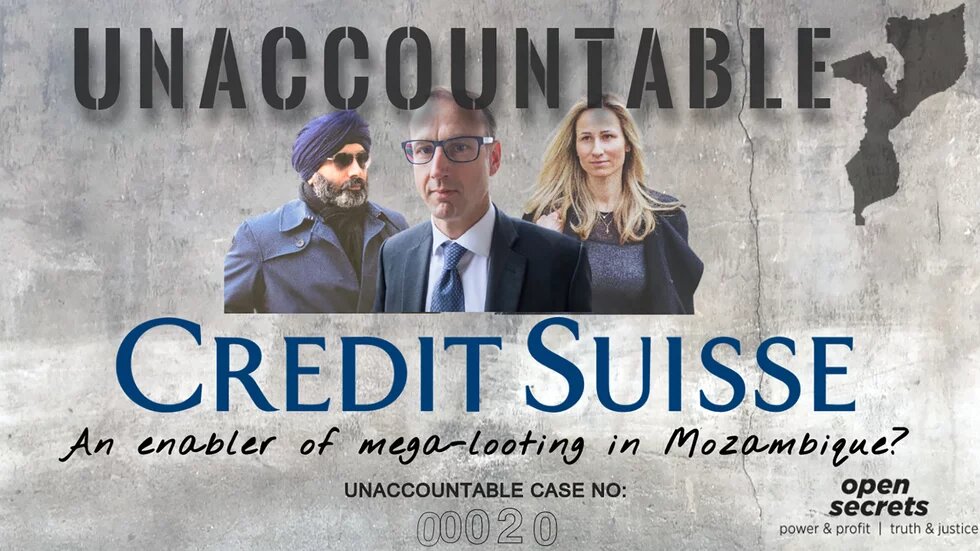

The scandal has prompted a litany of lawsuits in the UK, the US, Mozambique and South Africa against the politicians and private sector actors involved in the secret loans. In 2019, three senior Credit Suisse bankers, Andrew Pearse, Detelina Subeva and Surjan Singh, pleaded guilty in the US to conspiracy to violate US anti-bribery laws and to commit money laundering and securities fraud.

Could it be that only three bankers are responsible? Mozambican and US authorities believe that Credit Suisse should also be held to account for this fraud. Russian Bank VTB Capital has also escaped accountability and we return to them in a later instalment of Unaccountable.

Mozambique’s ability to respond to myriad social challenges is severely hampered by another crisis – its colossal debt. This debt is largely the product of a profiteering corrupt state, powerful global banks like Credit Suisse, and shipping companies, unscrupulous middlemen and predatory hedge funds. The victims are Mozambique’s people, pushed further into austerity to pay off an odious debt – conceived between corrupt local elites and banks such as Credit Suisse.

Mozambique’s security services go to sea

The background to the crisis is Mozambique’s “tuna bond” loans issued in 2013, purportedly to fund three new state-owned companies as part of a project to create a tuna fishing fleet and other maritime infrastructure. In reality, much of this money would be spent on maritime security and defence equipment, and the companies were all projects of Mozambique’s security services, the Serviço de Informações e Segurança do Estado (SISE). The three companies were Ematum (tuna fishing company); Proindicus (maritime security); and Mozambique Asset Management (MAM) (maritime repair and maintenance). MAM’s $535-million loan was arranged by Russian state bank VTB and Proindicus borrowed $622-million from Credit Suisse for its maritime security projects.

Mozambique does need to protect its maritime resources – it has a 2,700km coastline and is rich in fish and shellfish, which are vulnerable to illegal and unregulated fishing – a major security concern for most African countries. Mozambique also has vast and lucrative reserves of offshore natural gas. With oil and gas prices soaring at the time, the Mozambican government gave the assurance that it was able to repay the debt and provided guaranteed bonds bought by Credit Suisse and VTB.

Yet none of the projects embarked upon would capitalise on Mozambique’s resource wealth – rather the schemes were used to generate kickbacks for politicians and bankers at the expense of Mozambicans. Within the Mozambican government, the project was coordinated by the network of former president Armando Guebuza (president from 2005-2015), then finance minister Manuel Chang and senior state security official António Carlos do Rosário.

Contrary to all of the evidence, they maintain that the secret loans were undertaken for the protection of the country and benefit of the people. This was despite the fact that the equipment delivered is of no value and mounting evidence that their network of cronies received an estimated $200-million in kickbacks.

In order to conceal the existence of the new companies and the extent of the country’s debt, the Mozambican government insisted that the loans be kept strictly secret. The loans for MAM and Proindicus were not approved by Parliament, the Council of Ministers, the Central Bank and the Attorney-General – despite this being a lawful requirement. The money for the loans did not even reach Mozambique. Rather, the banks paid the money directly into the accounts of Abu Dhabi-based shipbuilder, Privinvest – the sole contractor for all three contracts. This violated Mozambique’s Constitution and public finance laws.

There was further evidence of corruption. An independent audit by US business intelligence firm Kroll showed that Privinvest had severely inflated the prices of the vessels secured through the deal. Privinvest quoted $22-million for the vessels, but they were found to be worth no more than $2-million by Kroll. Moreover, once delivered it was clear that the vessels would need a major refit if they were to catch tuna efficiently. Industry experts also found the feasibility studies on the Ematum and Proindicus projects to be worthless, while it is unclear whether one was ever conducted for MAM.

In 2016, IMF president Christine Lagarde described these loans as “clearly concealing corruption”. The IMF, a primary lender to Mozambique, was only informed about the loan to Ematum, and not of the loans to Proindicus and MAM. The revelation of the latter loans would lead the IMF to cut off access to credit in 2016. However, the IMF is not without blame. It had been privately warned about a second loan by a “Frelimo figure”. Further, financial surveillance is a key aspect of the work that the IMF does and the Mozambican government had a history of hiding loans in order to circumvent the requirements of the IMF. It is hard to see why the IMF was caught by surprise by this scandal, if it was indeed fulfilling its due diligence requirements.

***********************