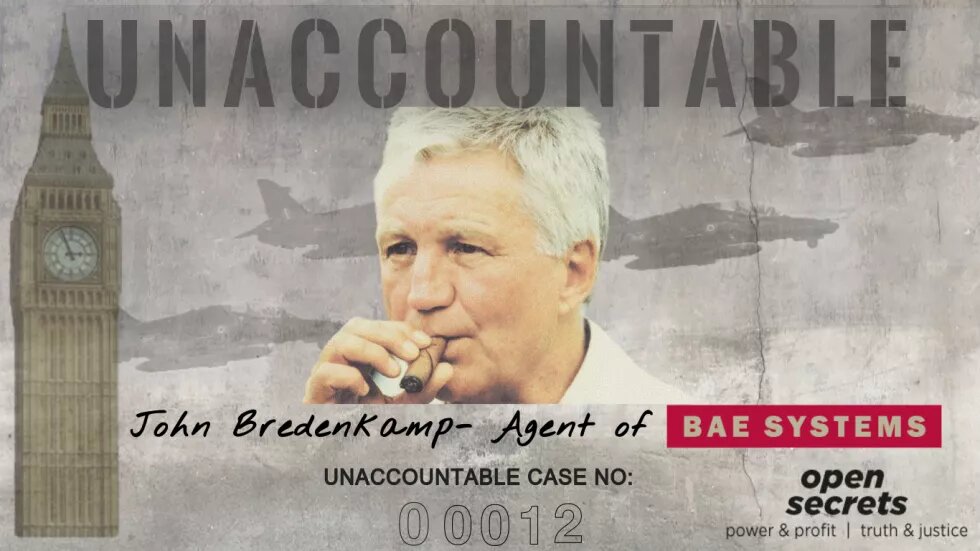

This week, Open Secrets continues to profile the corporations and individuals implicated in corruption in the 1999 Arms Deal but yet to be held to account. The European arms corporations that profited from the deal used a similar modus operandi – pay well-connected middlemen and agents to guarantee access to politicians and key decision-makers. This week we turn the spotlight onto John Bredenkamp, who was contracted by British arms giant BAE Systems in relation to the Arms Deal. This is the first in a three-part series detailing the lucrative relationship between BAE Systems and its covert international network of middlemen.

As the 23 June date set for Jacob Zuma and Thales’ next court appearance approaches, it is important for us to remember that they are in a minority of those implicated to see the inside of a courtroom. Zuma and Thales will (despite their best efforts) ultimately have their day in court related to their formerly clandestine arms deal era partnership. Others have been more successful in their attempts to remain unaccountable for their own dodgy dealings related to the Arms Deal.

The notoriously corrupt John Bredenkamp is a good example. There is a great deal of evidence, detailed below, that he used his political connections to influence the multimillion-dollar agreements to favour BAE Systems. Yet, despite being seriously implicated, lackadaisical law enforcement agencies around the world and botched investigations have left him, and many others, unaccountable. As the Thales/Zuma trial kicks off, it’s time that South African prosecutors dust off the old dockets and reconsider the evidence that has been largely ignored over the past dozen years.

BAE Systems and the 1999 arms deal

Upon the signing of the final agreements related to the multibillion-rand Strategic Defence Procurement Package on 3 December 1999, BAE Systems (previously known as British Aerospace) secured the biggest slice of the arms deal pie. The British arms company was awarded the contract to supply the South African Air Force with 24 of its Hawk trainer aircraft, as well as a second contract – along with its joint venture partner, Swedish Defence company, SAAB – to supply 26 of their Gripen fighter jets. These highly lucrative contracts were together worth R15.77-billion (valued at about R45-billion today) – more than half the total cost of the arms deal at the time.

BAE managed to land these contracts despite protests from heads of both the South African Air Force and the South African National Defence Force, who expressed their concerns about the exorbitant cost of BAE’s Gripen and Hawk, and its failure to meet the full requirement specifications.

So, how did BAE manage to secure these deals when the very institutions for which these aircraft were being purchased were in protest? The controversial choice only starts to make sense when examining the influential middlemen that they had on their side.

Enter, John Bredenkamp.

*********