In March this year a highly controversial piece of legislation was pushed through parliament despite strong opposition to it by many of Heinrich Boell Foundation's partners over the last few years. Here, one such partner, the Land & Accountability Research Centre (LARC), tells us why the pushing of the Traditional Courts Bill is so problematic, especially for rural women.

On 6 March 2019 Parliament’s portfolio committee on Justice and Correctional Services adopted the latest version of the Traditional Courts Bill (TCB) which has been in the parliamentary pipeline since 2008.

From its first introduction, it was opposed in a national campaign involving rural activists, civil society organisations and ordinary South Africans. Rural women and their organisations were at the forefront of opposition to the 2012 version of the Bill.

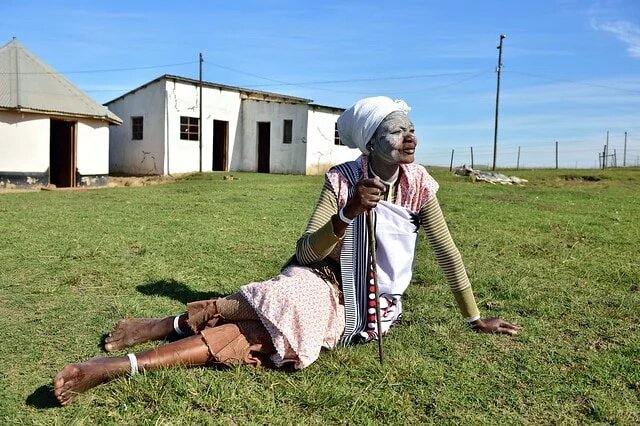

They attended public hearings and addressed Members of Parliament directly, recounting personal experiences at the hands of traditional leaders to highlight their concerns. They explained that the passage of the bill would exacerbate, not improve, their already vulnerable situation in patriarchal rural communities.

They made it clear that they did not object to customary law, or to dispute-resolution forums rooted in systems of customary law. Instead, they were objecting to the autocratic interpretation of customary law that pervaded the TCB. This unaccountable version of custom remains pervasive in the amendments that were adopted by the portfolio committee this week.

The amendments reject the principle that customary law is a system based on voluntary affiliation legitimised from the bottom up. Their starting point is that power and authority are centralised in the person of the traditional leader. Then and now the Bill locks people under the punitive authority of government-imposed traditional leaders with no option to choose other courts. It entirely ignores the “opt-out” provisions that rural people fought so hard to have included, which would have allowed them to exercise a choice whether to subject themselves to the authority of a traditional court, or not. This would have given effect to the affiliation-based nature of customary law and the constitutional right to choose a particular culture.

During the 2012 campaign against the TCB rural communities repeatedly made the point that legitimate traditional leaders would not need these types of powers. People already happily attend courts that they consider to be fair under leaders who have their community’s support.

Those who have opposed the opt-out provision, including previous committee chair Mathole Motshekga, have done so on the basis that an opt-out/in provision undermines traditional courts and traditional leaders. They argue that there is no similar option to opt in or out of other courts, for example, magistrates’ courts. This argument cannot stand for two reasons.

First, customary courts have enormous advantages for rural people. They are close to where people live and are steeped in the ways and ethos of the community. As long as these forums are run in a way that is perceived to be fair and legitimate people will make use of them. It is not the inclusion of an opt-in/out provision that undermines the legitimacy of customary courts, it is quite simply the conduct of those who convene them.

Second, the comparison with the common law courts system creates a selective and false equivalency. The Bill also excludes lawyers from the traditional courts system — an obvious divergence from the common law courts, which flies in the face of the argument for equivalence. South Africa’s Constitution and the highest court in the land have made it clear that customary law forms part of our legal system, but that it is to be interpreted and engaged with on its own terms, and not through the lens of the common law.

A constitutionally aligned approach would recognise that traditional courts are rooted in systems of law that function differently to the common law. As such they require a model that better accommodates the principles — such as voluntary affiliation — that inform the system of customary law. The point, as the Constitutional Court has shown, is to acknowledge that both systems are to be equally respected, not that one needs to replicate the other in order for it to gain respect.

But why does the inclusion of an opt-in/out provision matter in practical terms?

This is best illustrated when we consider the recent case of Mthizana-Base and others v Maxhwele and others [2019] ZAECMHC 11. This case, which was heard in the Eastern Cape, details how the local headwoman attempted to evict three women from their homes in order to make way for development projects.

She demanded that each woman pay an amount of R10,000 in recognition of the “chiefdom”, failing which she would confiscate their land. This was despite the fact that the women had occupied their homes for more than 10 years. They were subjected to threats and harassment when they refused to vacate, and one woman and her family were barricaded inside their home when a wall was constructed around them on the alleged instruction of the headwoman.

The women approached the police for assistance numerous times, but to no avail. Eventually one approached a local chief about the building taking place within her yard, and this is where this case is relevant for arguments about the TCB. The chief advised her to either “go to the magistrate’s court or instruct an attorney”, which the women duly did.

The Legal Resources Centre represented them and judgment in their favour was handed down on 28 February 2019. The headwoman was interdicted from interfering with their property rights and ordered to pay their costs.

Had the Traditional Courts Bill already been signed into law there is a strong likelihood that these women would have been locked into the customary dispute resolution system, which may not have been able to grant them the urgent assistance that they needed. They would likely have been forced to appear before the court of the very headwoman who was attempting to dispossess them.

This is an all-too-common reality for rural women and is part of the reason why rural women fought so fiercely for the inclusion of an opt-out provision during the 2012 process.

It is bitterly disappointing that the version of the TCB adopted by the portfolio committee last Wednesday takes us all the way back to a point where rural people are again deprived of the ability to choose.

This is a blatant undermining of the inherent democratic elements of customary law in order to privilege the few over the many, at the expense of rural women. As the TCB moves through the National Assembly and into the National Council of Provinces, civil society will be watching it closely and so will rural women.

_________

This article was first published on www.dailymaverick.co.za.