On May 7, 2014, in the significant marker of 20 years to democracy, 18.6 million South Africans at home and abroad came out to cast their votes.

The country’s fifth general elections were billed to be ‘the most important elections since 1994’. And indeed, as the first elections in which the first crop of ‘born frees’ – those born after the end of apartheid – would cast their votes, they were bound to be significant, whatever message they would bring.

However, for many, the phrase ‘the most important elections since 1994’ signified an expectation – or rather – hope, for change. Stories circulating in the media suggested that a drop below 60% for the ruling African National Congress (ANC) would incentivise an ANC leadership turn against President Jacob Zuma. While no one doubted an ANC victory, a 3 point slide from 65.9% to 62.15% seemed like a limp slap on the wrist for a ruling party that has spent the past five years mired in everything from sex scandals to grand corruption, not to mention an unforgivable tragedy. Three percent for the massacre of 34 mine workers by the police in Marikana? Really? Is that all? Three percent for the ANC’s non-chalant shrugging off of “Nkandlagate”, the president’s abuse of public funds for a lavish “security upgrade” of his private homestead in Nkandla? “After all these scandals, we now gave them a certificate to continue taking from the poor” was what one activist said in resignation.

The disappointing three percent was even more surprising given the tumultuous political shifts of the past 12 months: In December 2013 the country’s largest trade union, the National Union of Metal Workers (Numsa), announced that it would not endorse nor campaign nor financially contribute to the ANC’s campaign as has been custom since 1994. It also announced that it might form a workers political party to contest future elections. The move was a significant blow to ANC ally Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU), the country’s largest union federation, and suggested the federation’s imminent split. In August 2013 firebrand Julius Malema launched the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) party. Within months, the party’s signatures red berets were not an uncommon feature in universities, townships and public political debates.

Of course, when looked through a cool political or statistical eye, this is no surprise (in fact, South Africa’s Science Council predicted the results almost to the exact point percentage). In a press conference preceding the elections, ‘Arch’ Desmond Tutu reminded South Africans that state agents were no longer climbing trees or peering through windows to prevent intimacy between people of different races. And of his joy of watching black and white children mingle in middle class schools 20 years later. Thanks to the ANC, South Africa is a better place to live for the majority. There is probably not one impoverished South African whose life has not – in some way – been touched by access to water, electricity, housing or social grants brought by the ANC administration. It does not help that with the exception of the largest opposition party Democratic Alliance (DA), which is perceived to be protecting white elite interests, opposition parties have failed to inspire confidence. So while things are not good enough for the majority who rely on public services, the ANC still remains the majority of voters’ least worst option.

But was this, in-fact, an election with no surprises? An election that signifies that things have simply, give or take, remained the same?

There are two indications that the answer to that may be no.

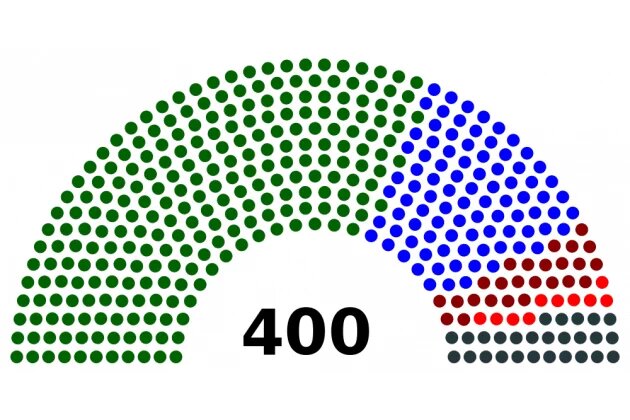

Firstly, while it’s true that on aggregate all that the ANC lost was a mere 3%, a closer look reveals important harbingers. Firstly, the DA’s electoral gains (from 16% in 2009 to 22%), and the EFF’s successful debut performance (6%) while less than what either hoped for, is important. Broken down into provinces and localities, it is clear that particularly in the metros, the DA’s share of the vote increased significantly, sometimes by up to 10%. The ANC’s fortunes, meanwhile, especially in urban areas, declined almost across the board, in some cities by 10%. Provincially, the same story is mirrored. While the DA gained significantly in every province, the ANC lost considerably, with the exceptions of the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu Natal (KZN) in which it rose by around 1%. Although the DA is breaking important ground in demonstrating the possibility of challenging the ANC, further gains are unlikely unless the party genuinely becomes more racially and economically inclusive, and finds ways to appeal to the majority of impoverished South Africans. While the EFF potentially could be the real challenger to the ANC in 2019, it still has to prove its staying power and avoid implosion like previous ANC breakaway parties. A key difference between previous breakaways and the EFF, however, is that the EFF presents genuine policy alternatives. Discontent with all parties can be seen in the voter turnout: once again, only 56% of those eligible voted.

Secondly, Marikana, Nkandlagate, public outrage over the introduction of highway e-tolls and perhaps above all – the ANC’s dismissive response to those (almost to the extent of pretending these didn’t happen, or if they did, it’s no problem, or it’s not their fault) forced a decisive shift in civil society.

Best capturing the mood was the ‘Sidikwe! Vukani! (Wake Up! We Are Fed up!) Vote No!’ campaign launched by a number of struggle stalwarts – among them former ministers, university vice-chancellors and current National Planning Commissioners. The campaign called on citizens to partake in an act of ‘tough love’ and vote against the ANC, either by ‘tactically voting’ (supporting a small opposition party) or spoiling their ballot. While not the first ANC veterans to do so, the campaign reflects the growing willingness across society to turn against the party and the declining sustainability of the ANC as a political home for a lifetime.

And it is in this sense that it was South Africa’s largest shack dweller’s movement – Abahlali baseMjondolo (AbM) – that pulled the greatest surprise. Days before the election, the left leaning, thousands strong movement announced its endorsement of the DA – a move that was met with shock and horror by those on the left. Not only is the DA popularly characterised as ‘anti poor’ and ‘pro white’, but also, since 2006, AbM has chosen to boycott elections, insisting on ‘No Land! No House! No Vote!’. Two weeks earlier, stating that “we are clear that the ANC has become a serious threat to society" and that “it is no longer enough to withhold our vote from the ANC” AbM invited all political parties ‘except the ANC’ to vie for their vote. After negotiations, both the Western Cape and KZN AbM Chapters signed agreements with the DA relating to land provision and housing. In a country where politics are identity driven, the willingness of AbM to suspend its ideology and use its vote to extract real promises is momentous. For the first time since 1994, a social movement used their votes tactically to strengthen their political influence. Whether the DA keeps its promises is another matter. It is a golden opportunity for them to demonstrate that they are committed to an inclusive and just society.

And so what does this all mean?

Identity plays a critical role in politics the world over. But in a fractured society like South Africa’s, where race overlaps with class, and historical mistrusts persists, it is decisive. While the DA is unlikely to ever be the party to take over from the ANC, a willingness to ‘play politics’ and strategically use elections as instruments of change – to suspend identity politics, in other words – will be a necessary, if insufficient measure to realising a more accountable political elite.

It is also positive that the 2014 elections injected greater political competition into the system. For those who identify South Africa’s democratic deficiency to be rooted in the ANC’s electoral dominance, the landscape has become more diverse. Whether greater opposition presence will strengthen parliament’s authority and influence is still to be seen, but there is no question that the country’s legislature will become a more politically relevant place. It is also positive that despite the difficult dilemma faced by disillusioned ANC supporters, the rather low voter turnout remained stable instead of dropping (56 % of total voting age population), indicating that South Africans do recognise and trust elections as an important (if insufficient) vehicle for democratic political participation.

Economically, should the EFF effectively use its parliamentary presence (and all indications are that it is competent enough to do so), it will force discussions of economic alternatives. Should the party perform well in the 2016 local elections, it is likely that both the DA and the ANC will need to take on issues of redistribution, access to land and resources more decisively to maintain their competetiveness. A challenge for the media, political parties, civil society (and political foundations) will be to foster informed and honest discussions about economic choices. Indeed, the confluence of COSATU’s breakdown and the death of the ‘old’ movement as signalled by Marikana – opens spaces for ‘new movement building’.

All in all, therefore, marginal electoral adjustments mask significant political shifts 20 years into South Africa’s democracy. In political seasons outside of spring, change takes time.