This year’s G20 process has felt like a rollercoaster: exhilarating highs, exhausted lows, and constant questions looping in our heads: Is this process meaningful? Can we influence it? Will the United States derail everything? And yet, even as the ride sped towards the Leaders’ Summit, many of us in civil society stayed strapped in, pushing for progress from the world’s largest economies and largest polluters. In this piece, I share my own reflections on the challenges and possibilities of engaging the G20 from a civil society perspective, particularly on issues of climate, energy, and food justice.

When I boarded this ride in October 2024, I knew very little about the G20. But like many of my civil society peers, I was willing to learn fast. What I didn’t expect was how quickly this year would reveal both the possibilities and pitfalls of trying to engage one of the world’s most powerful—yet opaque—political spaces.

A Promising Start, Quickly Derailed

This story began with a well-attended civil society gathering in Johannesburg in October 2024. Organisations from across sectors came to explore how the G20 might intersect with their work, cautiously weighing whether it was worth getting involved. Our discussions were organised along engagement strategy lines: the “insider track” of official engagement versus the “outsider track” of protest, critique, and public pressure.

But a crucial step was missed. That first meeting could—and should—have launched a formal Civil 20 (C20) platform, ready to take over the mantle from Brazil. Instead, early concerns about transparency and inclusion opened the door for competing groups to step in. The result was unfortunate: leadership disputes, parallel sign-ups, and a once-hopeful initiative quickly descending into confusion and mistrust. The original convenors eventually stepped back, and the C20 that emerged felt politically aligned, insufficiently representative, and often unaccountable to the wider civil society community it claimed to speak for.

This year’s work was hindered by the lack of a coordinated international civil society voice—something a transparent, inclusive, and functional C20 could have supported. Even if the engagement groups’ policy packs have limited influence on formal G20 negotiations, the process itself can still be valuable. When done well, it helps to align civil society campaigns across countries and organisations—inside the formal track, outside through public pressure, and behind the scenes through targeted advocacy.

Finding Our Own Way Forward

While the formal engagement mechanism faltered, climate and energy networks didn’t wait. By January, we were developing our own roadmap through capacity-building workshops with South African and African civil society partners. We mapped engagement opportunities—from opinion pieces to workshops, policy briefings to public protests. We committed to working inside, outside, and behind the scenes—wherever there was a chance to elevate climate and justice issues and influence the formal process in a more constructive direction.

From this collaboration emerged the African Civil Society Climate, Energy and Sustainable Finance Group (ACG20): an informal but effective coalition that sustained collaboration throughout a chaotic engagement year.

South Africa’s presidency had placed climate and African continental priorities at the centre of its agenda. Every priority had clear climate linkages, and G20 working group issue notes were peppered with climate references and potential outcomes to address African needs. This gave African civil society a foothold to push for an agenda that reflected community realities and needs: local access to climate finance; a just and equitable energy transition; protection from exploitative mineral extraction and air pollution; and solutions that tackle both climate impacts and chronic energy poverty. We fought to ensure that not only Southern economies benefit, but that local communities do as well, and that their voices are directly included in decision-making.

From Letters to Leverage

What began as a series of letters to South African G20 working-group leads evolved into coordinated joint positions that became our backbone for the year—solid, coherent African civil society inputs. These shaped our collective action both inside and outside the negotiating rooms: background briefings, behind-the-scenes support for negotiators, media interviews, op-eds, side events and protest messaging, as the G20 train barrelled toward its final moments.

And while civil society is mostly excluded from official G20 spaces, there were some notable exceptions, including the G20 Environment and Climate Sustainability Working Group’s Science-Policy Dialogue in September. South Africa, taking inspiration from Brazil, also attempted a formal “Social Summit” including both official and unofficial engagement groups. Well-intentioned though it was, the event—like Brazil’s experiment—came far too late and was too disconnected from the formal process to shape negotiations meaningfully.

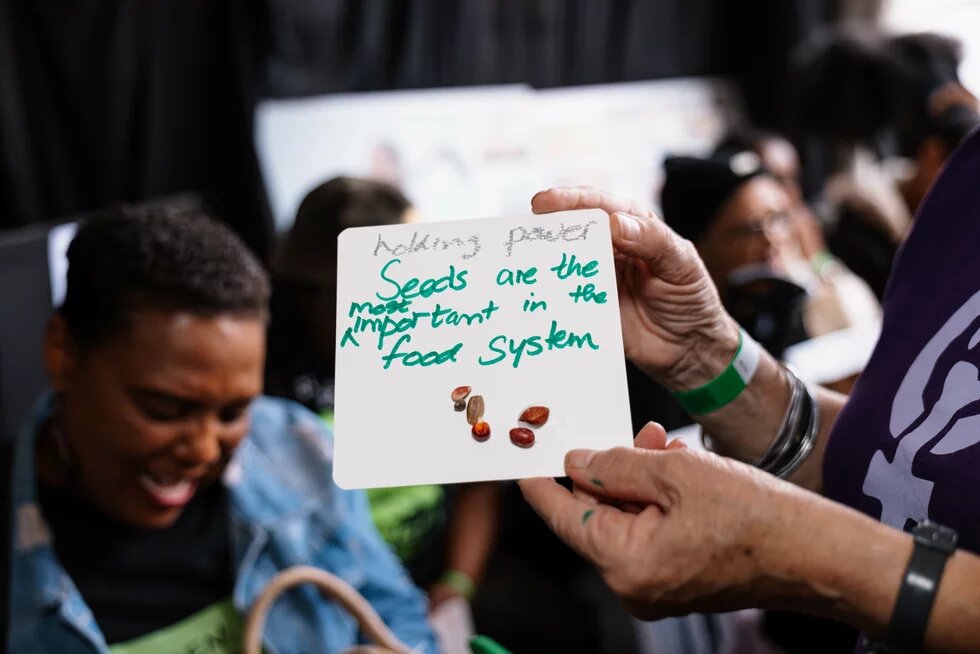

So we developed our campaigns and built our own spaces. In our food justice campaign, we unpacked what this meant with international and local experts, and dug into issues on the G20 agenda with civil society partners. In October we convened a round table that brought small-scale farmers together with officials from Brazil, Italy and South Africa to discuss their G7 and G20 food initiatives. And we participated in the civil society-organised “People’s Summit”—held under the banner of “We the 99%” at the historic Constitution Hill—where social movements gathered to articulate what the G20 refuses to hear.

Does Any of This Matter?

The scepticism never disappeared. Many of us kept asking:

Is this worth it? Are we actually making a difference? How would we even know?

These questions echoed amid wider debates about the G20, amplified by the US challenge to multilateralism—blocking, withdrawal, attacking, and insisting no consensus was possible without their participation—and by the “G20@20 Review” assessing the G20’s effectiveness and relevance.

With limited resources, civil society organisations must choose carefully where to invest their energy. But one thing is undeniable: hosting a G20 generates national attention. Media interest opens space for debate, and civil society voices—if organised—can shape public narratives. On that basis alone, our engagement had value.

A Climate Win, Against the Odds

Ultimately, the G20’s defining annual output is the Leaders’ Declaration. This year, keeping climate on the agenda at all, across working group and ministerial meetings, was a constant battle, with some wins and some losses along the way. By the final stretch, the fight was no longer just about content, but about whether a consensus text could be achieved at all, given the US withdrawal and its attempt to block consensus outcomes in its absence.

That a declaration emerged—and one that foregrounds climate—is, in my view, a win for both climate and multilateralism.

The final text, though imperfect, reads almost like a climate declaration from a Global South perspective: centred on impacts, resilience, and needs. Implementation remains thin, commitments voluntary, and finance commitments vague and lacking. But set against the backdrop of active obstruction from the US and some allies, President Ramaphosa’s success in securing a consensus declaration at the start of the Summit is politically significant. That 17 major economies and two regional blocs affirmed that climate remains a priority sends a clear signal: multilateralism can move forward even when powerful countries try to stand in the way.

What Comes Next

For many African civil society organisations, next year’s US-led G20 will not be the best use of scarce energy. Many will return to national campaigns and community work, as the G20 circus moves on.

But I believe our collective efforts have strengthened us. We leave with deeper relationships across African climate and energy networks, clearer collective positioning, and new tools for engaging in global processes that too often lack strong Global South voices.

The rollercoaster may be slowing, but we’re stepping off with clearer purpose, stronger alliances, and a renewed understanding that civil society must remain in global debates—even when the ride is rough.