In 2021, both Zambia and Zimbabwe were experiencing economic challenges such as rising rates of unemployment and limited opportunities for young people. The Zambian elections that year saw the youth coming out in large numbers to “protect” the vote that ushered Hakainde Hichilema into the presidency. The resounding impact of their role was produced by determination, strategic mobilisation and a united voice that the youth have the power to champion transformation in society. It raised a vision of “winds of change” blowing across the southern African region, inspiring hope that the youth in Zimbabwe and elsewhere could finally take their power as voters to determine electoral outcomes. Zimbabwean youth, however, marginalised in the country’s political processes and facing various structural and institutionalised barriers to participation, have not yet harnessed their demographic strength.

The United Nations Population Fund states that 62% of the country’s population is under 25 years old. Yet these numbers have failed to translate into votes, and there is evidence of increasing apathy among young voters. This behaviour is linked to the issues affecting the youth and how they have responded to the politics of the day.

Factors affecting the youth

There is little evidence to suggest that youth concerns are taken seriously by politicians and policymakers in Zimbabwe, an attitude that also extends to civil society and development partners. For example, the widespread use of a skills approach to address youth unemployment is itself problematic. Educated and skilled-up young people are still unable to find employment as the government has failed to generate new jobs and development partners are reluctant to support youth-led business ventures. Such failures to dissect the factors related to youth development result in further marginalisation of the youth, which in turn influences youth apathy towards governance processes.

The government’s approach is also top-down, tokenistic at the very best, and overridden by political overtones of dominance. This power dynamic is characterised by mistrust with an emphasis on control and management of the youth, rather than addressing their concerns in collaboration with youth stakeholders.

The major challenges facing the youth population are economic. The Zimbabwean economy has been in the doldrums over the past two decades, and the government’s promises of job creation are little but political gamesmanship. ZANU-PF’s election manifesto for the 2013 elections promised to deliver 2.2 million jobs. In 2018, it further promised to deliver 1.5 million houses. These are wild flights of imagination, as the latest ZimStat figures show. The limited number of available jobs are rarely separated from social networks, political affiliations and the politics of the local economy. Thus, the chances of youth employment are embedded in their social relationships and their ability to navigate politically. Unemployed youth are forced to seek alternative sources of income.

The informal economy is a viable alternative. In 2022, 85–90% of Zimbabweans had some engagement in informal activity, with the sector employing 2.8 million people, compared to 495 000 in formal employment. Thousands of graduates and school-leavers have been absorbed into what has been described as a “kukiya kiya” economy – unregulated, hustling-based activity driven by short-term survival and necessity including varying levels of illegal activities associated with youth vulnerability and poverty. Its driving attitude is known as “kungwavha-ngwavha”, combining “cleverness” and “crookedness” as a means to thrive. This is both a survival strategy and an accurate description of Zimbabwean society at large. The youth are trapped in this vicious cycle, with not much hope of turning the situation around.

Are the youth in Zimbabwe political game changers?

The participation of youth in governance spaces is not impressive. That is not to say that they have no desire to participate: they are inhibited by various structural and institutionalised barriers. Genuine spaces for political participation are limited and policy-making processes work from the top down. Even where policy is supposed to address their concerns, there is scant consultation with the youth in governance and developmental processes. By excluding young people from key decision-making positions and processes, this perpetuates a cycle of harmful policies and programming that is at best irrelevant, and at worst dangerous. The younger generation lacks trust in the older generation, and vice versa.

In focus group discussions held across the country, young people reported that they only feel appreciated by politicians during election seasons. This is just about the only time when policymakers express the will to solicit and engage with their views. It is also the time when they are “marinated”: given a few resources to start up small projects or promised policies that end up being ineffectual or not catering to the needs of all youth. For example, young people are asked to organise entrepreneurial groups and given broiler chickens or pigs as currency for their start-ups. In Cowdry Park in Bulawayo, where the current finance minister is running for parliament, youth were recently offered courses in a Red Cross first-aid programme along with promises of assistance to get jobs in the diaspora. The reality is that this is just politicking for their votes.

In the few spaces that are open for public consultation, it is only safe to participate if you belong to the ruling party and, even there, the youth voice is largely represented by the older generation. During public consultations for the Private Voluntary Organisations (PVO) Amendment Bill in 2023, young participants in Bulawayo reported that they were victimised and that the process was violent. A number of young people were recruited to act as “plants” in meetings, while some were fed alcohol to disrupt the proceedings. Opportunities to speak were managed by the older generation and programmed to support the ruling party. Such gestures of youth participation are merely decorative and do not yield results that cater to national youth challenges. The activity of Zimbabwean youth is also constrained by the violent political context in which they find themselves. Fear has been instilled in them as the political spaces are just not safe. They are cognisant of the post-election events of 1 August 2018, when civilians were shot and killed by the military. They are also aware of prominent opposition politicians who have languished in prison and can imagine what could happen to them.

Given all this, there are few avenues for youth to exercise agency. Some accept co-option into the system to access benefits while others pursue the escape-route option of leaving the country. Some have taken to social media to voice their political opinions, but they are not free from deliberate internet shutdowns, state censorship, arbitrary arrest or legal constraints. The 2021 Cyber and Data Protection Act was enacted to “increase cyber security in order to build confidence and trust in the secure use of information and communication technologies by data controllers, their representatives and data subjects”. As the Zimbabwe Independent newspaper commented, the Act “aims to punish the people who misuse and abuse the internet, social media and communication network”.

Voting engagement: from promise to apathy

Between the contentious 2013 re-election of Robert Mugabe and the 2018 elections following his removal from office, the registration of new voters between the ages of 18 and 22 increased phenomenally by 372%, and by 83% for those aged between 23 and 27 years. Voter turnout in 2018 was recorded at 85%, with ZANU-PF’s Emmerson Mnangagwa winning the election with 50.7% of the vote, against 44.6% for the MDC Alliance’s Nelson Chamisa. Many youths – especially first-time voters – said they believed that Chamisa had won the election and were disappointed with the result. They also cited the 2008 elections, which they believe Morgan Tsvangirai won outright but ZANU-PF and the army prevented the transition.

Coupled with this, the youth have no trust in the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission’s ability to conduct free, fair and credible elections. History has shown that the electoral playing field is tilted in favour of ZANU-PF and that this is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future. This all contributes to their conclusion that elections don’t change anything and hence their disinterest in any related activity.

Rural youth also say there is insufficient access to information pertaining to their rights and political development issues. There is very little consultation, and many youths reach the conclusion that voting does not make a difference, because the ruling party will not relinquish its power.

Young people view politics as a dirty game that is corrupt and scandal-ridden, characterised by electoral fraud which then leads to disputed outcomes. They see those involved in politics as being there only for self-enrichment, and not acting in the best interests of the voters. That is why young people do not see much reason to invest their time in processes that do not contribute towards improving their welfare. Politics and the voting processes do not foster any change.

The voter registration process for the 2023 elections presented more hurdles for youth. The cost is high and may require an additional US$2 for transport to and from the centres, which are not strategically located for easy access. Registration also takes time. Young people do not see any gain in sacrificing their time and hard-earned money to register to vote in an election in which they have no faith. Urban youth are concerned about their everyday hustles, and it is difficult to convince them even to register to vote. Youth voter registration was mainly facilitated by political parties, which provided free transport and monetary or material incentives for proof of registration. Civil society organisations which have been active in voter education programmes were not as effective as in previous years. This was largely due to the above-mentioned PVO Amendment Bill, as they had to contend with threats of closure and loss of funding. Passed in early 2023, the Bill has forced civil society into self-censorship.

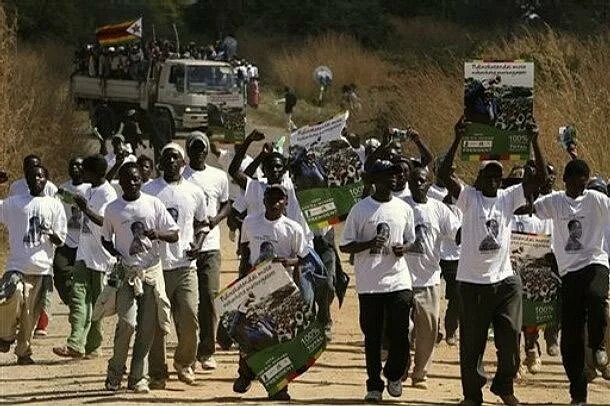

Political parties mobilise supporters to attend political meetings or rallies, and the youth are seen as the runners who make sure that this happens. For the 2023 election campaign season, all parties have been using a door-to-door strategy to sell their manifestos and unemployed youth have been at the forefront of working the campaigns. While they understand the importance of participation in elections, many youths in rural areas are willing to campaign for the candidate who gives them a few “goodies”. It is not uncommon for the youth, particularly males, to be given a few dollars or supplied with alcohol to disrupt rival contenders’ political meetings. Elections represent opportunities for the youth who describe their cooperation with politicians as “eating” or “drinking” them before they commit to voting for them. There is no loyalty involved. Whoever comes onto the scene is a potential meal ticket, no matter which political party they come from. The candidates are also potential sponsors of violence, but this tends not to worry the youth who work for them, the majority of whom are males. This may seem at odds with a theory of rational choice that assumes individuals will pursue options that best serve their self-interests. In this case, however, the rural youth are likely staring at poverty and could do anything for money.

They also don’t believe that their participation in electoral processes would be meaningful because the older generation wants to dominate and will not give them a chance or any opportunities. Few youths have made it onto party lists and they face a myriad of obstacles. Young people generally lack the financial muscle to compete with the established older generation, who have access to resources such as mines and land gained from political office or connections. These resources are not easily accessible to the youth. The selection process is also marred by violence within and between political parties. This violence often goes unpunished, sending a clear signal that it is politically rewarding.

Rural youth face a further disadvantage, compared with urban youth, due to a lack of access to information. Most of the youth from urban areas who make it to the candidate lists have received training from civil society organisations or are activists with access to information and training. Although most of these factors are attributed to structural politics, the youth have also failed to mobilise themselves to increase their representation in political spaces. These are clear gaps that need to be reflected on going forward.

Youth in political parties

For both rural and urban youth, the main space for political participation is in parties. However, their motivation for participation varies. While there are youth who genuinely support their respective political parties, in the rural communities it is almost compulsory to attend meetings. These are usually ZANU-PF meetings because the opposition is constrained by the need for clearance from security authorities and by threats of intimidation or violence from ruling-party elements. The violence is structural and institutionalised, creating an inescapable web that feeds information to the ruling party. The institution of traditional leaders, for example, is a vehicle for ruling-party mobilisation. The distribution of food aid and agriculture inputs is also politicised, and shadowy figures move around the communities, identifying those in opposition. Inevitably, participation in ruling-party structures becomes a matter of safety. The opposition also attempts to rally support in rural areas but their efforts are met with violence from ruling party-sponsored youths hired to disrupt their meetings and a hostile police force that is instructed to ban the meetings.

The political party structures include a wing specifically set up for youth members. The youth wing has its own leadership and is expected to shape the party’s direction by making recommendations to the main decision-making structure, mostly the elders. In the case of ZANU-PF, the elders are veterans of the liberation struggle who do not believe in the youth. Party leaders view the youth as foot soldiers to rally support for the party. The opposition has a similar approach. The youth wings are in place, but they are not safe spaces to express views openly and without repercussions. There is little they can do to shape policy without being reminded by the older generation that “we brought democracy”. In some instances, older party members even hold leadership positions in the youth wing. While the youth may raise their issues among themselves – such as addressing unemployment and the lack of access to resources – they are reminded of the need to “exercise discipline”. The party’s issues are not connected with the youths’ everyday concerns.

In one striking example, the ZANU-PF government passed a constitutional amendment to introduce a youth quota in the National Assembly. It provides for ten youths to be elected, one from each of the ten provinces of Zimbabwe. While quotas can be celebrated as a quick way to address the concerns of minority groups, this provision is nothing to celebrate as it entrenches the marginalisation of the youth. It is a short-term strategy to appease the young people who are applying pressure and demanding a seat at the table. It diverts attention away from the real impact of policy failures on the youth. The institutional and legislative framework of the quota views youth as a minority while, in fact, they constitute the largest segment of the population. It may appear to promote youth representation, but it is merely tokenism – and it causes a headache to even imagine the selection criteria necessary for ten members to represent 57% of the population.

Looking beyond the 2023 vote

In July 2023, one youth respondent said that registering to vote is nothing but “buttering bread for politicians to feed their swollen bellies and their entire families. We are just phantoms, used as begging bowls from the National Treasury and international aiders.” For many young people in Zimbabwe, the promises and dreams of a better future have been shattered by the nature of state politics. They contend that the only ones who have faith in the process are those who are politically connected or currently benefiting from the system. This depressed state of affairs and a bleak sense of the future accounts for the youths’ appetite to seek greener pastures outside of the country.

After the 2023 elections, it will be important to consider possible missed opportunities for the youth. They can convene to reflect on their pitfalls and reorganise themselves around common issues. This can form a base from which to lobby the government through its various structures. The challenge is to help the youth rethink their value in society and to encourage their participation in electoral processes. Non-violent participatory frameworks need to be put in place to ensure genuine youth participation, including measures that will bring in and support young women. The government has a lot of work to do to address the trust issues that are central to questions around legitimacy and to make the institutions of the state accessible, transparent and accountable to the youth.