Hugo Knoppert coordinates the Zimbabwe Europe Network (ZEN), a network of European secular, faith-based and developmental civil society organisations that support projects and partnerships in Zimbabwe. While welcoming the European Union’s attempts to re-engage with the government of Zimbabwe, Knoppert expresses concern that Europe’s short-term geopolitical interests will undercut EU support for human rights and civic freedoms and its censure of state repression in the country.

Hugo Knoppert interviewed by Katrin Seidel

Over the past two decades, the relationship between Zimbabwe and the European Union has gone through various ups and downs. This year’s election is only the second that EU observers have been invited to monitor since 2002, when the head of the EU Election Observation Mission was expelled by the Zimbabwean government. In your view, what is the current position of the European Union towards Zimbabwe, and particularly its government?

In 2002, the head of the EU Observation Mission had been vocal about widespread violations of human rights and civic freedoms. Shortly afterwards, he was ordered to leave the country. The Council of the European Union then imposed restrictive measures against individuals and companies in Zimbabwe accused of being responsible for human rights violations. Those measures were gradually removed, but the EU has maintained so-called “appropriate measures”, which suspend any direct development cooperation with the Zimbabwean government. Following the ouster of long-time ruler President Robert Mugabe in 2017, there was strong interest in European capitals to redefine the EU’s relationship with Zimbabwe. However, given the lack of substantial political and economic reforms and the further closing of democratic space in the country, such discussions soon lost momentum.

Currently, we are witnessing another European re-engagement aimed at normalising relations with the Zimbabwean government. It centres around the debt clearance process to resolve Zimbabwe’s debt arrears. This has been tried before, but this time the process is more promising since it is regionally led and more inclusive. Much hinges now on the elections, as they are seen as an important litmus test for the process.

It is important to note that, even though the form of engagement has shifted several times over the past two decades, European support towards civil society has been quite consistent and remains significant.

As you say, democratic space has shrunk further in recent years. Why do you think that the EU is interested in re-engaging now?

The European shift is mainly informed by geopolitical considerations. The war in Ukraine and, in particular, voting patterns of African countries in the United Nations General Assembly have led EU policymakers to reconsider their foreign policy direction. However, within this general shift, there are also country-specific considerations and characteristics.

Certain European diplomats in Zimbabwe have expressed a growing sense that previous strategies, and especially finger-pointing, have not worked. This fuels the push for a re-engagement narrative but I believe some of these sentiments lack historic awareness and deeper analysis. First, it is difficult to say if past strategies have or have not worked, without being clear on the objectives. Second, they assume that the EU took a confrontational approach in the past decade, which, according to my experience, has not been the case. In fact, there have been two previous genuine re-engagement attempts, in 2013 and again in 2017.

The Zimbabwe Europe Network has always been supportive of these attempts, but we also ask questions, particularly about the balance of engagement. In view of past attempts, a re-engagement strategy needs clear objectives and also a “Plan B” in case the human rights situation deteriorates rapidly, which is a scenario we have seen unfolding over the past few months.

How do civil society actors in Zimbabwe see the role of the European Union and its representatives in supporting their fight against closing civic spaces?

I think there are two main issues here. First, as part of last year’s shift towards re-engagement, the EU has been reluctant to issue public statements on human rights violations in Zimbabwe. Perhaps EU officials underestimate the impact of this silence, but it has been clearly noted by Zimbabwean civil society actors who feel the lack of solidarity. As one activist put it: “The EU is like your ex-girlfriend who walks into the sunset with another man.” While they acknowledge that some of the “quiet diplomacy” efforts have yielded results – for example, those related to the Private Voluntary Organisation [PVO] Amendment Bill that is threatening the work of civil society in Zimbabwe – there is the sense that the EU puts more emphasis on its relationship with the government.

This comes at a time of high uncertainty for a civil society faced with the recently signed “Patriotic Bill” and the PVO Amendment Bill. Even without the PVO Amendment Bill, the level of self-censorship amongst civil society actors is already very high. Most organisations cannot risk their registration and hesitate to work and speak on politically sensitive issues. What is happening in Zimbabwe is unfortunately not unique, and we have seen similar legislation being introduced elsewhere in the world. How European actors respond to it does, however, differ. In Zimbabwe, it seems that the EU is currently not positioning itself as clearly against violations of human rights and civic freedoms as it has done in the past.

At this point, it is important to remember the significant contributions Europe has made to the democratic processes in Zimbabwe. The 2013 Constitution is considered a modern and progressive governance framework that came about with significant European support. One of the key lessons is that it required sustained support in democratic processes, even, at times, with little or no progress.

This leads to the second key issue. There seems to be a lack of a long-term vision, with many European donors supporting activity-based projects. Considering the complexity and changing nature of Zimbabwe’s democratic space, we at ZEN believe that funding modalities need to be adjusted. A combination of factors has led to the weakening of civil society over the past five years and it is crucial for European actors to rethink their support mechanisms to ensure that civil society organisations will continue to operate despite the shrinking democratic space. This would, for example, include more institutional support and more flexibility in the funding arrangements.

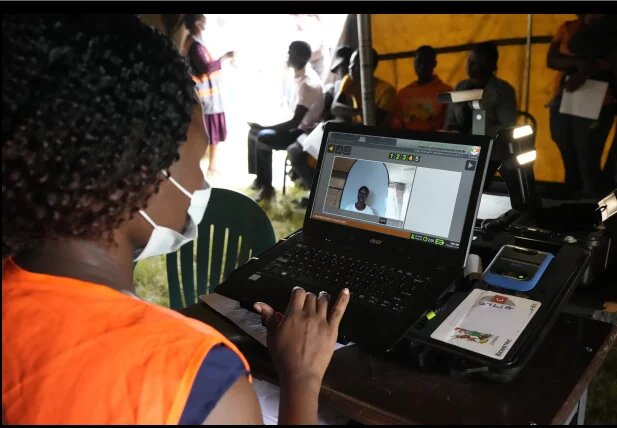

Much is at stake when Zimbabweans head for the polls on August 23. As you mentioned earlier, conducting peaceful, inclusive, credible and transparent elections is necessary for the country to break free from two decades of financial isolation. What would be the key points for the EU Election Observation Mission to best fulfil its critical mandate?

First and foremost, the assessment must be based on the full electoral cycle. The systematic attacks on both the opposition and civil society over the past few years have resulted in a severe shrinking of democratic space. I believe that we still don’t understand the full implications. In addition to repressive legislation, which was highlighted earlier, there is also the continued deterioration of the independence of the judiciary and the Zimbabwe Election Commission, which has a major impact on the credibility of the electoral process. It is important not to mistake the current relative calm prior to the elections for an open democratic space.

Second, there seems to be a tendency among some European officials to lower the bar, going from “free and fair elections” to “credible elections” and then to “peaceful elections”. It is important for the Election Observation Mission not to water down its standards for the elections, nor to tone down its findings. The 2018 EU EOM recommendations provide a useful reference.

Finally, European election observation has to be placed within a strategy for long-term engagement of the European Union with Zimbabwe.