January 2022 Household Affordability Index and Key Data

Key data from the January 2022 Household Affordability Index

The January 2022 Household Affordability Index, which tracks food price data from 44 supermarkets and 30 butcheries, in Johannesburg (Soweto, Alexandra, Tembisa and Hillbrow), Durban (KwaMashu, Umlazi, Isipingo, Durban CBD and Mtubatuba), Cape Town (Khayelitsha, Gugulethu, Philippi, Langa, Delft and Dunoon), Pietermaritzburg and Springbok (in the Northern Cape), shows that:

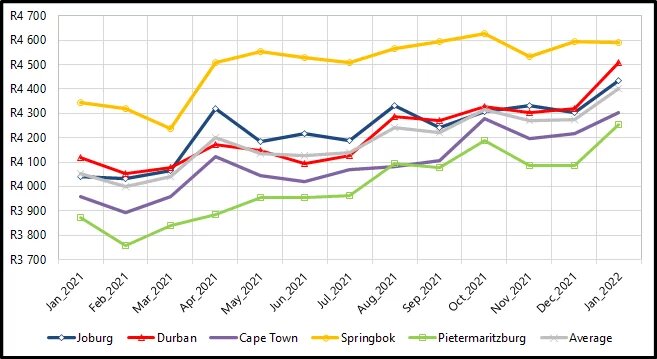

- In January 2022: The average cost of the Household Food Basket is R4401,02.

- Month-on-month: The average cost of the Household Food Basket increased by R125,08 (2,9%), from R4275,94 in December 2021 to R4401,02 in January 2022.

- Year-on-year: The average cost of the Household Food Basket increased by R349,82 (8,6%), from R4051,20 in January 2021 to R4401,02 in January 2022.

Statistics South Africa’s latest Consumer Price Index for December 2021[i] shows that Headline Inflation was 5,9%, and for the lowest expenditure quintiles 1-3, it is 6,2%, 5,8% and 5,4% respectively. CPI Food inflation was 5,9%. The Producer Price Index for November 2021[ii] shows that agricultural inflation was 8,1%.

Table 1: Household Food Baskets showing month-on-month (December 2021 to January 2022) and year-on-year (January 2021 to January 2022).

Figure 1: Total cost of Household Food Baskets from January 2021 to January 2022.

In January 2022, of the 17 foods which are considered the core foods which should reasonably be found in most South African homes, and of which are prioritised and bought first, 15 out of the 17 foods increased in price.

In the total Household Food Basket, 35/44 foods increased in price. Price hikes where across the board. A 2,9% month-to month spike is very high. In monetary terms, it averaged at R125,08. The year-on-year price of the Household Food Basket (January 2021 to January 2022) is standing at an average of 8,6%, with a Rand-value increase of R349,82. The average cost of the Household Food Basket at R4401,02 in January 2022 is very high.

Joburg, Durban and Pietermaritzburg are now showing annualised inflation of over 9%: Joburg at 9.7% (R391,69), Durban at 9,6% (R393,59); and Maritzburg at 9,8% (R380,86). Cape Town is marginally lower at 8,8% (R346,80).

Workers

The National Minimum Wage for a General Worker in January 2022 is R3 643,92. Transport to work and back will

cost a worker an average of R1 344 (36,9% of NMW), and electricity an average of R731,50 (20,1% of NMW). Together transport and electricity, both non-negotiable expenses, take up 57% (R2 075,50) of the NMW, leaving R1 568,42 to secure all other household expenses. If all this money went to food, then for a family of 4,5 (the latest ratio of how far a wage for a Black South African worker must go)[iii], it would provide R348,54 per person per month. This is 44% below the Food Poverty Line of R624 per person per month.

The proposal on the table for the NMW increase in March 2022 is CPI Headline +1% (even less than last year, which was a +1,5%)

Applying inflationary linked increments to a poverty-level base, just keeps workers in poverty from one year to the next. That the increments are linked to inflation for the previous year and not the projected inflation for the year ahead, deepens worker poverty. Workers spend most of their wage on transport, electricity, and food. December’s CPI puts annualised inflation on public transport at 9,9%, electricity at 14% and food at 5,9%. Projecting forward for 2022: fuel prices are set to increase with international crude oil prices on the up; Eskom has applied for a 20,5% hike in tariffs and food prices, impacted on by both electricity and fuel increases, amongst local climatic and agricultural constraints, and global factors (and speculation), are likely to rise. It means that a CPI Headline + 1% will not cover the real inflation rate experienced by millions of workers, and that the value of the NMW, already at a poverty-level, will erode further.

Statistics South Africa’s latest Quarterly Labour Force Survey shows that in the 3rd quarter of 2021, the number of Black South Africans who are unemployed now exceeds the number of Black South Africans that have a job (unemployed = 11,2 million vs. employed = 10,7 million).[iv] The expanded unemployment rate for Black South Africans stands at 51,1%. 565000 Black South African workers lost their jobs in the last quarter. Every single job lost is money lost to the economy. That thing you are producing just became that much harder to sell. It is a death spiral. You sell less, so you produce less, and so you employ less workers and those that are still employed watch their wages dwindle from almost nothing to nothing. The hollowing out of workers wages then ignites the meltdown, because you are then dealing not only with millions of wages no longer available to the economy, but the wages that are still available, are so low and have to spread so much further to support so many more people, that they are unable to demand anything more than basic survival goods, and then businesses left right and centre start falling.

The value of the wage is important. If we want to get the economy moving, increasing the National Minimum Wage to a level which allows workers and their families to live healthily and productively, whilst providing a little bit more to demand goods and services beyond food, lights, taxi fare, would be an investment in getting the economy off its knees. Wages are valuable assets to us if we use them well. And know their worth in an economy.

A CPI Headline +1% increase is not a desirable outcome; it is simply removing a desperately needed financial asset from the economy and pushing the country closer to the abyss.

Women and children

In January 2022, the average cost to feed a child a basic nutritious diet was R776,29. Over the last month, between December 2021 and January 2022, this cost increased by R28,34; and year-on-year, it increased by R55,13 or 7,6%.

As children grow older their nutritional needs differ and the cost increases. In January 2022:

- It cost R684,06 to feed a small child aged 3-9 years of age per month.

- It cost R743,33 to feed a small child aged 10-13 years of age per month.

- It cost R788,36 to feed a girl child aged 14-18 years of age per month.

- It cost R889,41 to feed a boy child aged 14-18 years of age per month.

In January 2022, the Child Support Grant of R460 is 26% below the Food Poverty Line of R624, and 40% below the average cost to feed a child a basic nutritious diet of R776,29.

In February of last year, government chose to increase the Child Support Grant by R10. Perhaps it is ignorance, or short-sightedness on government’s side which does not see proper nutrition as important for our millions of children and the future of our country and all of us in it? But it happens ever year where the annual increase becomes more and more ridiculous as to suggest that this is not a mistake; it is intentional. A Child Support Grant set at nearly a third below the food poverty line and 40% below the cost of a basic nutritious diet becomes an instrument to institutionalise inequity amongst Black South African children. Perhaps there are a million other explanations for not prioritising our children’s nutrition and health, however in the absence of reason, we might better look at the consequences to see government’s intentions.

For media enquiries, contact: Mervyn Abrahams on 079 398 9384 and mervyn@pmbejd.org.za.

-------

[i] STATSSA (2021). Consumer Price Index December 2021. Statistical release P0141. 19 January 2022. Statistics South Africa. Pretoria. P5 and 8. See Link: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0141/P0141December2021.pdf

[ii] STATSSA (2021). Producer Price Index November 2021. Statistical release P0142.1. 15 December 2021. Statistics South Africa. Pretoria. P11. See Link: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P01421/P01421November2021.pdf

[iii] STATSSA (2021). Quarterly Labour Force Survey, Quarter 3, 2021. Statistical release P0211. Statistics South Africa. Pretoria. P28-29, 46-47. See Link: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02113rdQuarter2021.pdf

[iv] STATSSA (2021). Quarterly Labour Force Survey, Quarter 3, 2021. Statistical release P0211. Statistics South Africa. Pretoria. P46. See Link: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0211/P02113rdQuarter2021.pdf