This article considers the multiple roles that women activists have occupied in two different contexts: firstly, in the fight against colonialism, as co-liberators alongside their male counterparts, and secondly, present-day feminist activists (with limited support from their male counterparts) who challenge both political and patriarchal forms of oppression that are harmful to women. These two contexts reveal similarities and differences in the role of women under conditions of oppression that are conducive to institutional and structural inequality, with women being the first casualties. African women’s fight against racial oppression under colonialism was a fight for fundamental freedoms that was entrenched in international human rights, largely in the form of civil, political and socio-economic rights. However, it is debatable whether those hard-fought freedoms are experienced and enjoyed by the average woman today.

This article proposes that existing power structures in present-day African governments – which were largely birthed in “liberation movements” against racial oppression and fought for by women and men – have done little to advance feminist movements. Demands for equality, bodily integrity and dignity are ongoing as women confront a different kind of oppressor who perpetuates their marginalisation in political, socio-cultural and economic spaces. Patriarchy is the common thread of both colonial and post-colonial times.

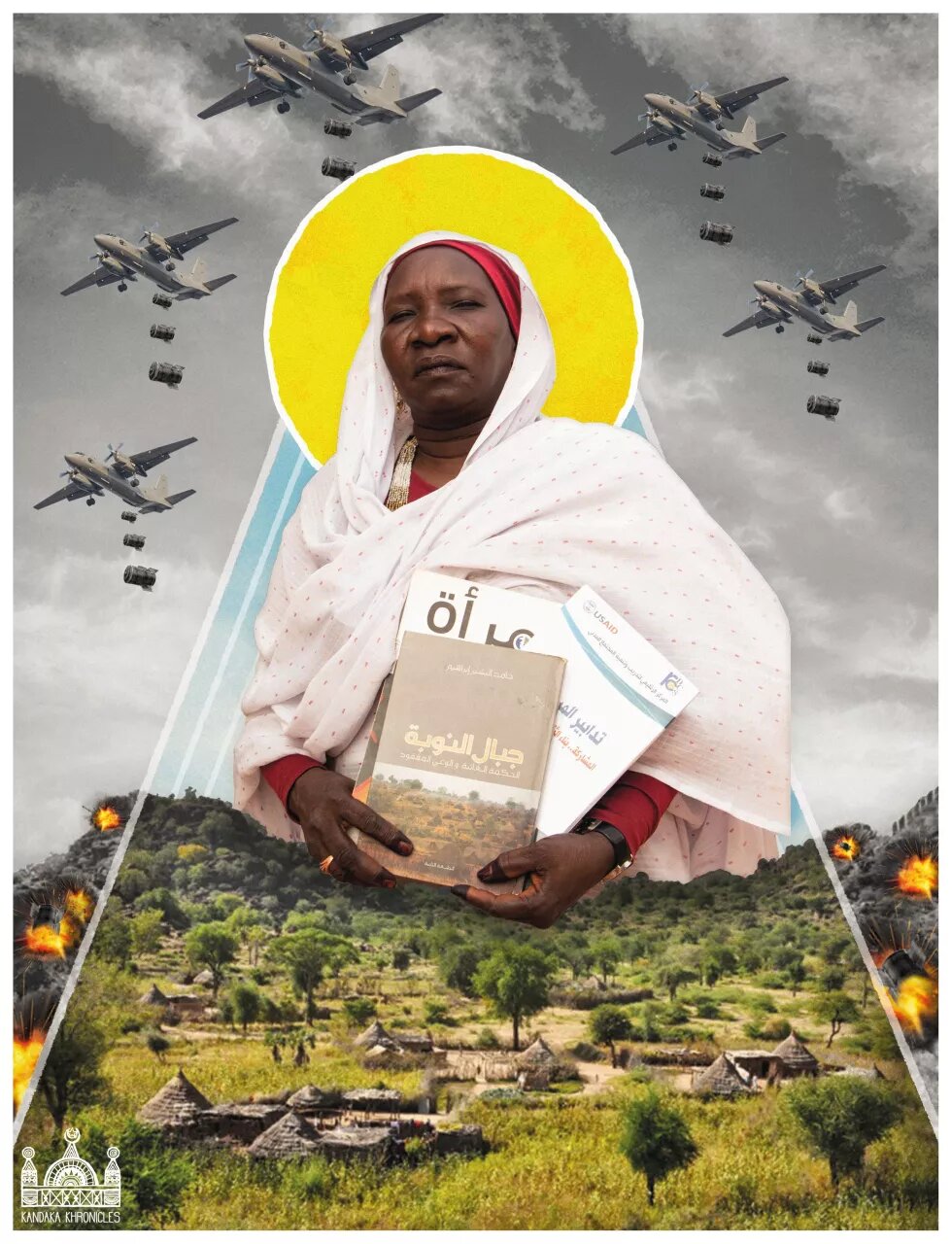

Women played a central role in the liberation struggles that catapulted African nations from the bondage of colonialism to political emancipation. Women fought alongside men in the bushes, organised marches in towns and cities, fundraised for the liberation movements, became exiles, and raised children from birth to adulthood in the midst of bullets, hand grenades, bombings, arbitrary arrests and imprisonments, while also being subjected to unremunerated commercial and domestic labour. The burden invariably fell on women to teach their children to appreciate the battles being fought for political freedom, and to revolt against oppressive racist systems that sought to dehumanise the very concepts of African pride and heritage.

A critical analysis of women’s roles during this period refutes as blatantly false any assertion that they were passive or uninvolved. Yet it is also true that these fierce and resilient women, who fought alongside men in the liberation trenches, were indiscriminately raped, beaten, abused and marginalised. The intricacies of patriarchy in the context of racial and political subjugation created a complex existence for women – as victims, survivors, leaders, nurturers, guerrilla fighters and social agitators – that continues to fan the flames of African feminism.

The article asserts that the challenges encountered by women during the colonial era, of being deliberately positioned as subservient to men, propelled them to join these liberation movements. Yet the challenges of gender-based inequality and violence rooted in colonialism continued into present-day African patriarchal governance. Furthermore, post-colonial concepts like “gender mainstreaming”1 and the sprinkling of female candidates in political positions have failed to address the deep-rooted inequalities which African women were subjected to during colonialism and in the liberation struggles.

These struggles have not gone far enough to shift the demographics of access to, and the enjoyment of, basic rights that are still enjoyed by a few at the expense of many. If this assertion is not true, then why has only one African country to date boasted a woman as its elected president? Why do we still have women earning the accolades of the “gatekeepers of patriarchy” in political organisations, women whose influence seems limited to defending – usually by their silence and inaction – the continued subjugation and degradation of women and girls? Why are the most egregious forms of gender-based violence met with deafening silence from prominent women’s organisations and networks? And why, if women were so clearly instrumental in the emancipation of Africa from colonial oppression, are they still in an obvious fight for the most fundamental rights?2 Never have these questions been more poignant than in the time of Covid-19 which has exacerbated and amplified the conditions that cement women’s political and socio-economic exclusion.

Colonialism Amplified Feminist Activism and Consciousness

Prior to the colonial era, women’s voices in decision-making processes in African societies were embedded in the cultural values and commercial activities of communities where women were central figures.3 Yoruba women provide a good illustration of women as partners in commercial activities such as long-distance trade.4 As they negotiated with foreign and local traders and merchants, these roles also fostered political skills to preserve economic stability and peaceful relations in their communities. Because of the influential positions they held and the wealth they had acquired, these Yoruba women enjoyed privilege and power.5

This is not to say that there was no patriarchy prior to colonialism, nor that men and women were equal. Where women have enjoyed some degree of independence, the responses of men ranged from acceptance to accusations of witchcraft.6 But the level of patriarchy and equality differed from one society to another, and there was certainly some element of matriarchal hegemony that was diminished by colonial structures. For example, pre-colonial pastoralist women in northern Kenya were responsible for herding small livestock and processing primary products such as milk, meat and skins, and they exercised considerable power and influence over the distribution and exchange of these products. However, the Kenyan colonial government sought to integrate this pastoralist way of life and social structure into the colonial economy.7 As a result, women lost the status, power and dignity they derived from their pastoralist roles. Suffice to say that, with new power structures that placed them at the fringes of social, political and economic decision-making, colonialism redefined the role of most women in African societies. Land concessions and loss of control of their economy effectively excluded women from meaningful participation in African societies and led to an unfamiliar economic dependence on men. As women lost their positions in the society, a harmful form of traditional patriarchy became entrenched in the African way of life through the imposition of colonialism.8

Matriarchal hegemony was replaced by a new kind of male domination under the camouflage of racial oppression. Patriarchy and colonialism changed gender dynamics and introduced unprecedented levels of gender inequality with economic and social consequences. When European colonial powers negotiated only with male chiefs on key economic issues like oversight of taxes and governance, the role of female chiefs decreased. In Nigeria, as the economy became more and more dependent on cash crops for exports, Nigerian men and European firms dominated the distribution of rubber, cocoa, groundnuts (peanuts) and palm oil. This pushed women into the background and into the informal economy.9 Furthermore, the customary land-tenure systems that had provided women across Africa with access to land were disrupted by land commercialisation that favoured those who made money from the sale of cash crops.10

Insofar as slavery and colonialism can be identified as pathways to gender inequality, the emergence of feminism can also be linked to a collective resistance by women against a patriarchal system of governance rooted in colonialist structures that excluded them because of their race and gender. Indeed, if feminism is the theory of political, economic and social equality of the sexes,11 patriarchy is the antithesis of feminism. Even a benevolent patriarchy conflicts with feminist theory as it accommodates only some women in positions of power while leaving the rest behind.

By joining the liberation struggles against colonialism, women – consciously or subconsciously – embraced the fundamental principles that are embodied in feminist activism: they acted from their desire for the fruits of substantive equality. Women were game-changers in fighting against the racial and gender oppression of colonialism. For example, Bibi Titi Mohamed recruited at least 5 000 members to the women’s wing of the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU). She accomplished this in a short period by tirelessly mobilising women’s networks through rallies, marches and fundraising events.12

Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, born in 1900, was only 19 when she left her home in Nigeria to further her studies in England. She returned a few years later and became active politically, founding the Women’s Union of Abeokuta.13 Her organisation challenged corruption and unjust taxes as well as the lack of women’s representation in decision-making structures.14

Mabel Dove Danquah of Ghana is another prime example of a feminist and political activist mobilising against colonial powers. Through her writing and journalism, she contributed to the struggle for independence through the main political party, the Convention People’s Party. She was commended for her efforts by its leader, Kwame Nkrumah. In 1954, she became the first African woman to be elected to parliament by popular vote.15

The socially constructed inequalities between men and women that took root during colonialism worsened during the liberation struggles across Africa, despite women’s participation in those struggles. This is demonstrated by widespread acts of gender-based violence in the form of rapes and beatings, exclusion from decision-making, and the general marginalisation of women by their male comrades.

The women who remained in the villages also played central roles in this period, acting as informants for the liberation movements, organising demonstrations, providing hideouts, and maintaining the home environment. Yet they too were the targets of rape, by both colonial apologists and members of the liberation movements.

Even after independence, the disregard and diminishment of women’s participation in liberation struggles were reflected in the naming of major institutions and infrastructure. The names and faces of male liberators were affixed to universities, airports, roads, business centres and national currencies. Women were rarely afforded the same level of national recognition and respect.

Contemporary African Political Structures and Feminism

As noted in the previous section, colonialism had social, economic and political consequences for women in terms of their marginalization and exclusion from power. These consequences were woven into the social and political fabric of liberation struggles, as evidenced in the sex based and gender-based discriminations that women became increasingly subjected to and that were normalised by the political structures who led the liberation struggles in different African countries. Post-colonial gender constructs of men and women continued to position women as inferior to men and accorded them the status of minors. Guardianship and marriage laws often took away women’s ability to make decisions for themselves with regard to, for example, land rights, property rights, sexual health and reproductive rights, and even the right not to be raped in marriage.

In response, African feminists took up their position to challenge the patriarchal structures embedded in African governments that were reflected in their policies, laws and practices. In the Charter of Feminist Principles, African feminists declared that, “[b]y naming ourselves as feminists we politicise the struggle for women’s rights, we question the legitimacy of the structures that keep women subjugated, and we develop tools for transformatory analysis and action”.16

The harms inflicted by colonialism and the inequalities arising from that dark era are not easily reversed. The 2018 Global Gender Gap Index reported that it would take 135 years to close the gender gap in sub-Saharan Africa and nearly 153 years in North Africa, where the influence of religious systems dictates the societal and economic position of women.17

African feminists have fought for the rights of the girl child and the inequalities she suffers as a result of abusive patriarchal culture and discriminatory laws and practices.18 Clear examples include child marriages, lack of access to education, and the inequality between boys and girls that starts in primary school and widens throughout the educational process. Although Africa continues to register the highest relative increase in total enrolment in primary education among regions, the rate of enrolment for girls is lower than the rate for boys.19

Statistics vary from country to country in Africa. For instance, the government of Guinea embarked on a national strategy to prioritise girls’ education and introduced reproductive care for pregnant girls. At the other end of the spectrum is Tanzania, led by a government that implements policies detrimental to the rights of girls and in complete conflict with feminist aspirations for equality, such as banning pregnant girls from completing their education. In addition, “pregnancy rates for young women with no education are 52 percent, versus only 10 percent for young women with secondary or higher education”.20

Another example of state-sanctioned disempowerment and degradation of women is demonstrated by anti-feminist governments. Gender-based violence is wielded against women who are themselves politically active or who may only be related to those whom the government has targeted as a means to silence critics, the media, and members of opposition parties. This practice is common in despotic countries like Zimbabwe, where abductions of women political activists often result in sexual abuse and rape. It is rare for African governments to intervene to prevent widespread abuse of women, especially when it is unleashed by state security forces or through politically driven violence. A recent example to the contrary is the inauguration of a Gender-Based Violence Management Committee by President Muhammadu Buhari and the government of Nigeria in response to gender-based violence that occurred during the Covid-19 pandemic.21

Conclusion

This article has offered insight into the roles of women in various historical contexts. In pre-colonial Africa, women’s worth and dignity were validated by the critical contributions they made as drivers of social cohesion, as decision-makers in the home, and as respected stakeholders of economic resources from land to food. Colonialism brought significant setbacks and undermined women in their previously revered roles.22 These losses have been difficult to overcome. Even as women warriors joined arms with their male comrades or supported the anti-colonial struggle from their homes, they were subjected to gender-based violence and discriminatory treatment.

It can be argued that feminists in post-colonial Africa have made successful inroads in the public discourse on gender equality. Yet the social and economic effects emanating from pre-colonial Africa still resonate in forms of female disempowerment in the lives of women and girl children. Feminist discourse has strengthened the public condemnation of child marriage, even though this is still widely practised. Women’s and girls’ right to education is widely acknowledged, even though statistics show that girls enrol at lower rates than boys and, because of pregnancy and domestic work, are more likely to drop out. And although state-sponsored violence is still meted out against women, it now meets with international condemnation and the threat of African leaders being hauled before regional and international criminal courts. The feminist movement has made some measurable gains, but more is required for equality, dignity and opportunity to be availed to all.

- Josephine Ahikire, “African Feminism in Context: Reflections on the Legitimation Battles, Victories and Reversals,” Feminist Africa 19 (2014): 7–23, http://www.agi.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/429/feminist_africa_journals/archive/02/features_-_african_feminism_in_the_21st_century-_a_reflection_on_ugandagcos_victories_battles_and_reversals.pdf.

- Gumisai Mutume, “African Women Battle for Equality,” Africa Renewal (July 2005), https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/july-2005/african-women-battle-equality .

- Niara Sudarkasa, “‘The Status of Women’ in Indigenous African Societies,” Feminist Studies 12, no. 1 (1986): 91–103.

- An ethnic group in West Africa, mainly in Nigeria, Benin, Togo and parts of Ghana.

- Abidemi Abiola Isola and Bukola A. Alao, “African Women’s Leadership Roles Historically,” IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science 24, no. 9, ser. 5 (September 2019), 107–118, https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol.%2024%20Issue9/Series-5/B2409050508.pdf.

- Onaiwu Ogbomo, “Women, Power and Society in Pre-colonial Africa,” Lagos Historical Review 5 (2005), 49–74.

- Fatuma B. Guyo, “Colonial and Post-Colonial Changes and Impact on Pastoral Women’s Roles and Status,” Pastoralism 7, no. 13 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1186/s13570-017-0076-2.

- Guyo, “Colonial and Post-Colonial Changes”.

- Shiro Wachira, “Financial Inclusion is Key to Tackling Africa’s Gender Inequality,” World Economic Forum, 13 July 2018, accessed 28 April 2019, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2018/07/financial-equality-for-africa-s-women-farmers.

- Isola and Alao, “African Women’s Leadership”.

- Kathy Caprino, “What Is Feminism, and Why Do So Many Women and Men Hate It?” Forbes, 8 March 2017, https://www.forbes.com/sites/kathycaprino/2017/03/08/what-is-feminism-and-why-do-so-many-women-and-men-hate-it/?sh=57894ae87e8e.

- Kwasi Gyamfi Asiedu, “Africa Has Forgotten the Women Leaders of Its Independence Struggle,” Quartz Africa, 16 March 2019, https://qz.com/africa/1574284/africas-women-have-been-forgotten-from-its-independence-history.

- Alaba Onajin and Obioma Ofoego, “Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti: and the Women’s Union of Abeokuta,” UNESCO Series on Women in African History, January 2014, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000230929?posInSet=1&queryId=ca2d14da-6436-43b4-a71d-c1d07d1e7765.

- Asiedu, “Africa has forgotten”.

- Asiedu, “Africa has forgotten”.

- “Preamble to the Charter of Feminist Principles for African Feminists,” African Women’s Development Fund (2006), http://www.africanfeministforum.com/feminist-charter-preamble.

- World Economic Forum, “The Global Gender Gap Report 2018”, World Economic Forum, http://reports.weforum.org/global-gender-gap-report-2018.

- The African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child was adopted by the African Union (then the Organisation of African Unity) in 1990 and came into force in 1999.

- World Economic Forum, “Global Gender Gap Report 2018”.

- World Bank, “Factsheet: Tanzania Secondary Education Quality Improvement Program (SEQUIP),” World Bank, 31 March 2020, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/factsheet/2020/03/31/tanzania-secondary-education-quality-improvement-program-sequip.

- Temilade, “President Buhari Inaugurates Gender-Based Violence Management Committee,” Courtroom Mail, 11 June 2020, https://www.courtroommail.com/president-buhari-inaugurates-gender-based-violence-management-committee.

- Ogbomo, “Women, Power and Society”.