Expanding on the United Nations Women’s Rights Convention, Tunisia became the first Arab country to incorporate into its laws the notion of gender-based political violence. Can this concept now be incorporated into international instruments to benefit more women across the globe, starting with UN Women’s 2021 Generation Equality Forum?

This study is part of the series "Shaping the Future of Multilateralism - Inclusive Pathways to a Just and Crisis-Resilient Global Order" by the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung's European Union and Washington, DC offices.

Download the study "Shaping the Future of Multilateralism - Outlawing gender-based political violence: Can Tunisia’s example carve a multilateral path for others?"by Besma Soudani Belhaj and Najla Abbes

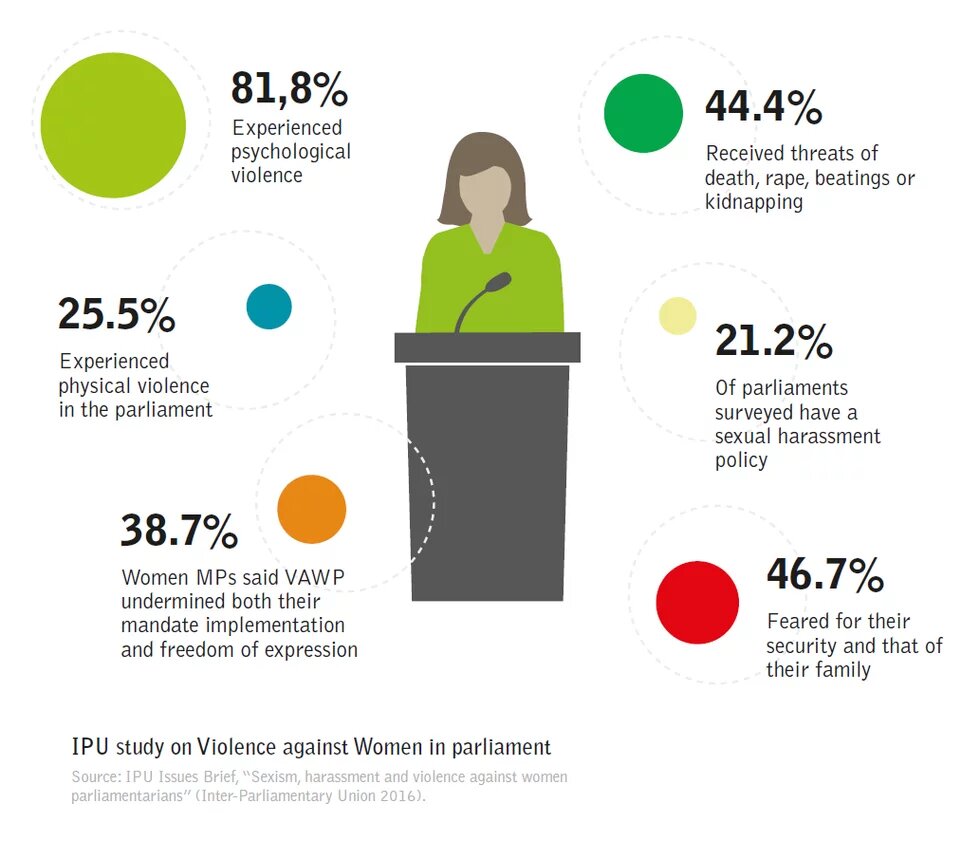

Violence against women is a daily reality for too many women and girls around the world, especially affecting those who are the most marginalized and vulnerable. But one form of such violence particularly impacts women seeking a role in their society’s political life: physical, sexual, or psychological harm based on their gender and meted out in a way that reinforces men’s control over politics. This violence has negative effects not only on the general well-being of women by preventing them from fully participating in professional, economic, social, and political spheres, but also on their societies that are deprived of their wider contributions.

And yet such violence generally is not recognized by law, a circumstance that leaves prospective women leaders vulnerable to discrimination and often excluded from political life. This is especially true -- though not exclusively – in countries making the transition to democracy, where patriarchal traditions and nascent legal systems combine to create seemingly insurmountable obstacles to women’s participation in society and politics. The organization we co-founded, the Ligues des Electrices Tunisiennes (LET, the League of Tunisian Women Voters), encountered exactly these obstacles as our country emerged from a quarter century of dictatorship with the revolution of January 2011.

The result was a years-long campaign to, first, successfully press for a guarantee of equality in the country’s new Constitution, and then to draw on that provision and on international legal principles and texts to fight for the passage in 2017 of Law 58, the Organic Law Related to the Elimination of Violence against Women. Adoption of that measure made Tunisia the first Arab country to incorporate into its laws the notion of political violence based on gender, one of 19 countries that have criminalized this form of violence. For some countries, such laws were adopted only after shocking violence against women in the political sphere that spurred public outrage, such as in the case of Bolivia. It had been the first country in the world to pass such legislation, but only after a record of attacks against female municipal leaders, including the 2012 assassination of a municipal councilor who refused to resign her post.

Following adoption of the law in Tunisia, LET is leading a new campaign in solidarity with women across the world, with the goal of integrating the notion of gender-based political violence in international legal texts. The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW, also known as the United Nations Women’s Rights Convention) served as a crucial basis for Tunisia’s new law. Yet, neither it nor other international documents reference gender-based political violence. Because such texts provide key guidance for countries developing their own laws, the absence of this provision deprives countless women in most of the world’s other countries of a clear basis for advancing such additions to their own laws.

In the course of this action, LET is working with peer CSOs in the region and with U.N. agencies to advocate for the principle of acknowledging and circumscribing political violence against women in international conventions and other legal texts. Such an initiative may have particular resonance in countries experiencing wrenching transitions such as Tunisia’s if the impetus comes from a country in the southern Mediterranean that witnessed a human rights revolution.

UN Women’s Generation Equality Forum in 2021, a review and update of the goals outlined in the 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action on women’s rights worldwide provides an opportunity to introduce and define the concept of violence against women in politics as one of the global challenges that hinder women’s political participation; especially considering the growing – though still insufficient -- number of women leaders in politics.

Gender equality in a political revolution

LET, founded amid the revolution that began in January 2011, was the first Tunisian civil society organization to be accredited by the Independent High Authority for Elections (ISIE) [1] as an official observer of the October 2011 elections for the Constituent Assembly. LET’s goal was to contribute to the national effort of establishing an inclusive democracy for men and women, specifically by ensuring a role for women in political life, starting with the Constituent Assembly election. For LET and other feminist organizations that were among the surge of civil society organizations (CSOs) helping launch this new democracy, it was a chance to persuade those in public policy to adopt the principle of gender equality in Tunisia’s new legal texts and practices, based on international conventions and treaties.

LET has become a pioneer in civil society election observation in Tunisia from a gender perspective. More than 300 trained short-term and long-term observers are distributed across the country. In times of elections, they report to LET all cases of political violence against women, and those accounts form the basis for the organization’s comprehensive reports, advocacy, and recommendations to decision-makers, including the ISIE.

When the new Constituent Assembly was in place and began working on a new constitution for Tunisia, LET and other civil society organizations (CSOs) pressed for the document to guarantee gender equality. As a result of this participatory process of the democratic transition, Tunisia adopted a new Constitution that, in Article 46, guarantees equal rights between men and women and protection from gender-based violence.[2]

But during the 2011 election and subsequently, our hundreds of female observers witnessed and recorded from testimony repeated incidents that made clear a disturbing trend: women candidates and political activists were being targeted for various forms of physical, sexual, or psychological abuse, not based on their political programs or proposals, but simply because they are women.

The new constitution, thus, became a starting point for feminist CSOs to advocate for the application of these principles of gender equality in legal texts and practices. LET appealed to a range of political and civic stakeholders, conducted seminars on gender-based political violence, and advocated with major bodies, including the elected Assembly of the Representatives of the People (a unicameral legislative body that replaced the Constituent Assembly), to integrate the concept into the electoral law. To no avail.

LET then was invited in early 2017, along with other major civil society actors, to contribute to the drafting of an organic law on violence against women. LET noticed that the first draft of the legislation did not include any specific reference to political violence. We were able to outline the distinctiveness of such violence with extensive evidence drawn from our gender-focused election observations, and presented the case that such violence must be recognized by the Tunisian State. LET presented a study making that argument to the Minister of Women, Family and Childhood during the discussion of the bill before the parliamentary committee.

In addition to the evidence that such offenses exist, the legislation ultimately was based on Article 46 of the new Constitution as well as on the 1956 Code of Personal Status[3] and international conventions, specifically the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).[4] Tunisia had ratified CEDAW, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1979, under the dictatorship, but with reservations. The post-revolution government in 2014 officially lifted all specific reservations that had allowed it to evade certain provisions.

CEDAW does not explicitly mention political violence in its generic definition of gender-based violence. However, LET emphasized Tunisia’s ratification of this convention and stressed that political violence is a distinct form of violence, and that this type of violence also should be acknowledged and eradicated to adhere to the spirit of the convention.

The resulting achievement was Law 58, the Organic Law Related to the Elimination of Violence against Women, [5] adopted on Aug. 11, 2017. Article 3 integrates the concept of gender-based political violence, defining it as “any act or practice based on discrimination between the sexes, the perpetrator of which aims to deprive women or prevent them from exercising any political, partisan, associative activity or any fundamental right or freedom.” Article 18 criminalizes such acts, stating, “Anyone who commits political violence is punished with a fine of 1,000 dinars. The penalty is increased to six (6) months' imprisonment for a repeat offense.”

From Tunisia to the world

In addition to being the first Arab country to incorporate the concept of gender-based political violence into its laws, Tunisia is one of 19 countries that have criminalized such acts. But during the drafting stage, the concept of gender-based political violence was rejected initially not only by policymakers but even by civil society, on the basis that the notion is not included in international conventions and texts and therefore could not be incorporated into Tunisia’s domestic laws. Opponents also argued that such acts were covered by provisions on other forms of violence included in the law, such as material, physical, moral, and economic violence.

These arguments illustrate the central role that international legal instruments such as CEDAW play in guiding countries developing their own national legislation. And it makes clear the need for international instruments to acknowledge and address gender-based political violence in order to ensure more women benefit from such protections around the world going forward. Furthermore, a country from the southern Mediterranean that has undergone – and continues to struggle with progress in – its own democratic transition might be especially persuasive in disseminating such a concept.

With this understanding and mission, LET prepared, in partnership with the Heinrich Böll Foundation, a series of initiatives to identify these gaps and develop initiatives for U.N. committees to support this concept and propose it to U.N. member countries as a future legal basis. Among the first steps was a study to introduce the concept of political violence and its causes and consequences for the civil and political rights of women and for the place of women in decision-making.

The absence of women in politics was not limited to women who were deprived of their freedoms and rights but was also reflected in public policies, laws, and regulations that organize societal and economic relations. The acts of violence that target women active in civic and political life have a dissuasive effect for any female citizen who has the will or intention to become a public figure or a politically active person. The cynical argument that politics is brutal and that criticism and attack are inevitable for women seeking to compete with men in a traditionally male-dominated sphere simply normalizes such violence against women in the field of politics.

Based on LET’s years of collected testimonies from women who were victims of political violence in their local communities when they started getting involved in political life, such attacks intensify even further when the women report or sue the male assaulter. In other cases, a woman might be forced to seek the protection of another man -- whether her father, husband, or son, for example – in the face of violence by other men they encounter in their political activism. If the woman is fortunate enough to have supportive male relatives, she may be protected; but some women reported to researchers that their male relatives actually turned against them instead, taking the side of the perpetrator. Hence, in the best-case scenario, the woman’s safety in politics would have to be guaranteed by another male who is more sympathetic towards her political activism.

In this challenging patriarchal environment, many of those women would have little choice but to give up. In Tunisia, this is even more likely in the interior of the country, where males are even more dominant in the public sphere. In those rural areas, women would fear the social pressure more, especially from their small communities, where the paternalism is evident in behavior such as referring to women as being the daughter of Mr. X or the wife of Mr. Y. In one of the rural areas of Tunisia’s northwest, LET received testimony from a female electoral candidate who had a dispute with a male opponent. After assaulting her in public, he called her husband to “come and take her home.” The female candidate described the situation as particularly humiliating and gave up her candidacy a few days before the election.

That case and many more illustrate how gender-based political violence leads to a reluctance by women to enter politics and play a leadership role in their communities. In this case, women would revert to purely economic participation in other work that they might consider a safer environment than politics and with more immediate compensation for their efforts. Hence, politics becomes of secondary importance and represents an environment of the utmost intimidation.

The higher the position a woman gains, the more likely the intimidation is to occur. An emblematic case is one in which a woman municipal counselor who served as head of the Arts, Culture and Education Commission played a major role in her community from the onset of the sanitary crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. Despite her active presence on the public scene – and likely because of it -- she was the target of verbal violence from members of the Education Union in her governorate following her order to shut down one class that did not respect sanitary protocols, even though this was within her purview as the president of the regional office for parents and students in her region.

Women near the top of the political hierarchy in Tunisia, such as female members of the elected Assembly of the Representatives of the People, are experiencing an increasing incidence of explicit violence, whether in recorded plenary sessions or within their parliamentary commission meetings. Offenses ranged from moral defamation and bullying in public to outright physical assault and death threats. Such violence is an extension of all kinds of discrimination against women in the political sphere. Since the promulgation of the law, more and more female politicians are speaking up about cases of psychological and verbal intimidation against them in politics, however only few of them filed legal cases that are still under consideration by the court.

Although Tunisia passed its unprecedented law criminalizing and punishing political violence against women, there is still a lot to be done in terms of raising awareness and using that law to deter attempts to intimidate women from participating in political life. That will require extensive efforts to raise public awareness of the violence and its consequences for the whole society, and educating legislative bodies on how to use this new law effectively to prevent abuses and prosecute cases when they occur.

Such domestic efforts should be accompanied and reinforced by a global campaign to acknowledge and criminalize political violence against women in international laws and conventions. The first step will be overcoming denial of the existence of such violence, which remains a taboo subject in too many corridors of power as well as in societies writ large.

Given the moral role and influence of international standards, the United Nations would be the vector of change for guiding decision-makers and opinion leaders and prodding national legislatures of member countries. Signatory states must heed the fact that, while gender-based political violence currently is not covered in international texts, 19 countries already have acknowledged and proscribed such acts as an infringement of the principle of gender equality.

Opportunity in 2021: UN Women’s Generation Equality Forum

Between March and June 2021, UN Women, with co-hosts Mexico and France, is organizing global civil society gatherings to review and update the 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. This Generation Equality Forum aims to “secure a set of concrete, ambitious, and transformative commitments to achieve immediate and irreversible progress towards gender equality,” according to UN Women. The events “will bring together governments, corporations and change makers to define and announce ambitious investments and policies.”

The forum will be a place to introduce the concept of political violence against women and could pave the way to review the relevant international conventions to define and integrate this concept in the following international texts:

- The Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women

- The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

- The Convention on the Political Rights of Women

- The Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women

- U.N. Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security

Political violence should be clearly integrated and defined in these international texts as a distinct form of gender-based violence to challenge harassment and violence against women in political contexts.

LET’s roadmap includes the important recommendation to transform the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women into a binding convention. To succeed in this mission, LET proposes two paths of advocacy: a government path and a civil society path. LET is leading the effort of an interactive preparation between the Tunisian state and various civil society stakeholders in order to identify the best tools for successful advocacy with the United Nations.

Conclusion

The goals outlined here – to ensure more consistent and effective implementation of Tunisia’s law against gender-based political violence and to achieve incorporation of such measures in international conventions and other texts – is admittedly ambitious. But multilateral forums and texts have tremendous impact on public policy and public opinion in individual countries, making such efforts essential to global progress on women’s rights generally, and female participation in civic and political life specifically.

Tunisia must not remain the only Arab country to have such a law, and the number of countries that have achieved this milestone worldwide must be expanded dramatically from the current 19. LET is working collaboratively with other feminist civil society organizations in Tunisia, with the Tunisian government, and with the international community to make it happen. But 10 years after the revolution, the atmosphere in Tunisian politics is very tense and incidents of violence generally, as well as violence against politically active women, are increasing. This is a constant reminder that the adoption of Tunisia’s law was only the beginning of a long-term goal to ensure such attacks are no longer considered normal.

An international consolidation of this law in conventions and similar global legal texts would provide an additional protective layer to women in politics and reward -- rather than punish -- their political activism. After 10 years of democratic transition, Tunisia and other countries of the Global South can inspire the international community to take further steps to preserve women’s dignity in political and civic life. Cementing these rights in global documents would create an international legal arsenal to fight threats to the political integration of women worldwide.

[1] The Independent High Authority for Elections (in Arabic: al-Hay’a al-‘Ulyā al-Mustaqilla lil-’Intikhābāt, in French: Instance Supérieure Indépendante pour les Elections) is a governmental agency established in the aftermath of the elections, and which is in charge of organizing and supervising elections and referendums in Tunisia. Its role was particularly significant in managing the phase following the death of former President Beji Caid Essebsi in July 2019, as the Authority had to deal with an unprecedented situation while the Constitutional Court was still not established. The current head of the Authority is Nabil Baffoun.

[2] Article 46 of the Constitution: The State undertakes to protect the acquired rights of women, supports them and works to improve them. The state guarantees equal opportunities between women and men to assume different responsibilities and in all fields. The State works to achieve parity between women and men in elected councils. The state is taking the necessary measure to eradicate violence against women.

[3] The Code of Personal Status or CSP consists of a series of Tunisian progressive social laws, promulgated on August 13, 1956, and in which family laws were enacted containing fundamental changes, the most important of which is the prohibition of polygamy, the withdrawal of guardianship from the man and the making of divorce in the hands of the court instead of the man.

[4] On April 23, 2014, The United Nations (UN), confirmed receipt of Tunisia's notification to officially withdraw all its specific reservations to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). By doing so, Tunisia became the first country in the region to remove all specific reservations to the treaty.

Reference list:

Accelerating Progress for Gender Equality by 2030. (n.d.). The Generation Equality Forum. https://forum.generationequality.org (accessed May 5, 2021)

Generation Equality Forum. (n.d.). UN Women. https://www.unwomen.org/en/get-involved/beijing-plus-25/generation-equality-forum (accessed May 5, 2021)

Législation du secteur de la sécurité en Tunisie (Law 58). (2017,11 August). Le Centre pour la gouvernance du secteur de la sécurité, Gèneve. https://legislation-securite.tn/fr/node/56326 (accessed May 5, 2021)

L’Instance Supérieure Indépendante pour les Élections. (n.d.). http://www.isie.tn (accessed May 5, 2021)

Our values. (n.d.). LET – Ligue electrices tunisiennes. https://liguedeselectricestunisiennes.com.tn/en/ (accessed May 5, 2021)

Tunisia: Landmark Action on Women’s Rights. (2014, 30 April). Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/04/30/tunisia-landmark-action-womens-rights (accessed May 5, 2021)