January 2021 Household Affordability Index

The January 2021 Household Affordability Index, which tracks food price data from 44 supermarkets and 30 butcheries, in Johannesburg (Soweto, Alexandra, Tembisa and Hillbrow), Durban (KwaMashu, Umlazi, Isipingo, Durban CBD and Mtubatuba), Cape Town (Khayelitsha, Gugulethu, Philippi, Delft and Dunoon), Pietermaritzburg and Springbok (in the Northern Cape) shows that:

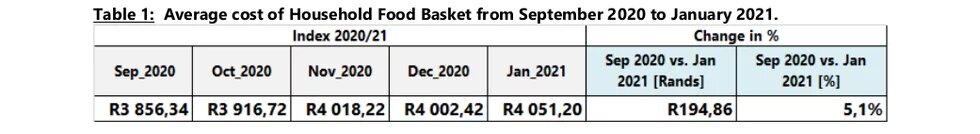

- In January 2021: The average cost of the Household Food Basket is R4 051,20

- Month-on-month (between December 2020 and January 2021): The average cost of the Household Food Basket increased by R48,78 (1,2%).

- Over the past five months (between September 2020 [the first data release] and January 2021): The average cost of the Household Food Basket increased by R194,86 (5,1%).

The average cost of the Household Food Basket increased through September 2020 to November 2020; prices then dipped slightly in December 2020 and have increased again in January 2021. The average cost of the Household Food Basket in January 2021 is now at its highest level since the start of the expanded collection in September 2020.

The main foods that are driving higher increases in the Household Food Basket over the past five months continue to be the core foods which most South African households reasonably expect to have in their homes and which are required for all basic food preparation and which are necessary so that families do not experience hunger: maize meal (15%), rice (3%), cake flour (3%), white sugar (5%), sugar beans (33%), samp (7%), cooking oil (4%), potatoes (4%), onions (2%), and white and brown bread (4% and 4%).

High levels of inflation on these specific foods are problematic for several reasons:

- These core foods must be bought regardless of price escalations.

- The higher cost of core staple foods means that less money is available to buy other foods which are important for proper nutrition: eggs, dairy, meats, and fish (essential for protein, calcium, and iron), vegetables and fruit (essential for vitamins, minerals, and fibre); and therefore, have negative consequences for overall household health and well-being and the ability to resist illness.

- The higher Rand-value cost of a basket of food has become unaffordable. It has breached the level of the National Minimum Wage, which in January 2021 is R3 321,60.

- Because prices have risen on the staple foods, foods which are common in nearly every South African home, it is reasonable to suggest that the impact of high food prices is being felt very widely in society; and that a large majority of families are struggling to afford sufficient food.

Most of the financial support made available by government to support families during the initial stages of the pandemic was withdrawn in October 2020 – it lasted just 6 months. The R350 Covid Relief Grant, which is so little, but shockingly so important, ends in 4-days’ time. Government has chosen to withdraw support in the middle of a pandemic when almost nothing has gone back to normal and almost everything has got worse. The vast majority of South Africans now face the second, and possibly third and fourth waves of Covid-19 with less money in our pockets than we had at the start of the pandemic in March 2020. We have no or little savings, almost no capacity to absorb shocks; we have lost our jobs, our wages have been cut, we work fewer hours. At the same time food prices, electricity prices and transport prices continue to climb. People we love are dying.

How is it possible that we allowed government to stop providing relief and not intervene to reduce the cost of expenses viz. regulate and bring down the prices of core staple foods, to subsidise public transport, and to cut the cost of electricity?

It seems trite to ask if government is doing its best to support us during one of the worst periods of our lives.

From our most recent conversations with women, we are hearing that we might however have a short window period of grace. Women, who were able to keep up with stokvel payments, say their families are in a much better position than families who were not able to do so. Most stokvels survived 2020: women tell us that they were able to carry on making payments by sacrificing their own health and nutrition needs and using some of the social grant top-ups on Child Support and Old-age Grants. Using their own strategies and saving part of the 6-month top-ups, women have been able to build up some resilience.

The food secured through the stokvel pay-outs in December are an absolute life saver. These core staple foods typically last through to March or April in a normal year. This year the food will finish sooner because families must share food with those whose food has run out and because the start of the new school year has been delayed. The grace period will end in February, after this time, women tell us – things are going to be very hard as many more families are going to find themselves very hungry.

Women tell us that they recognise that (1) the pandemic will be with us for another year; and (2) they are on their own now. Women will delve deep into their resources and talents, their relationships and connections and find a way to survive. “What can we do? We hustle. We eat less so our children can eat, we find someone, anyone to borrow money from and then find a way not to repay them. Everybody is hustling to sell something, make something, grow something, beg, and borrow, … start something, anything to survive. There is no rest, there is no peace” (Umlazi, Durban 21 January 2021).

While neo-liberal institutions such as the IMF and World Bank are encouraging governments to go big on economic stimulus and to spend to keep economies going and to defer dealing with debt till after the pandemic; our government’s approach seems to be razor focussed on austerity: reducing the deficit, freezing public sector wages, cutting back social and public expenditure.

In a time of a pandemic, the private sector and the super-rich, who are risk averse, rarely make investments in the economy. The magnitude of spending that we need to keep the economy alive, to ensure our public sector functions properly, and to support and protect families is likely only through the state. If the state does not act now and act big to spend and to support those in need, it is likely that our post-pandemic economic recovery will be slower and we will find ourselves in a deeper crisis post the pandemic. We will not be able to pay back any debt if our economy, our public service and infrastructure, and society has collapsed.

For more information and media enquiries, contact: Mervyn Abrahams on 079 398 9384 and mervyn@pmbejd.org.za; or Julie Smith on 072 324 5043 and julie@pmbejd.org.za.