As Zimbabwe approaches elections on 30th July 2018, it is worth reflecting on the various developments that have taken place since the last election in 2013. As may be recalled, the 2013 election brought Zanu-PF back into power after the interregnum of the Global Political Agreement and the Inclusive Government. The outcome of the 2013 elections raised more questions than answers especially given the magnitude of Zanu-PF victory. Few countries have witnessed repeatedly a government that has led its country into penury being returned to power with an increased majority and popularity. This seemed a Zimbabwean way of defying both common sense and the logic of political economy!

The election, which common sense would suggest would lead to Zanu-PF building on the small measure of economic stability created by the Inclusive Government, has rather led to a vicious internal faction fight within Zanu-PF, the fracturing of the opposition MDC-T, and economic paralysis due the total absence of coherent policy by the government. This was predictable to some analysts and commentators (RAU. 2010), and took no account of the growth of the securocrat state (Mandaza. 2016). From the comfort of hindsight, the growing crisis in Zimbabwe is entirely predictable and the 2018 elections would stand as the bearer of bad news. This paper gives an outline of what the 2018 elections scenarios could be and concludes that there is the high possibility of a disputed electoral outcome which may push the country into further crisis.

The Aftermath of the November Coup

Several points are now clear.

The first has to do with the unresolved problems of liberation movements in Southern Africa, and Zimbabwe in particular. Liberation movements in power face the problem of transforming themselves into political parties and abandoning the commandist ideology that drove them into power. This is a regional problem, as Roger Southall has so eruditely described for Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe in his analysis, Liberation Movements in Power (Southall. 2013). For Zimbabwe it is embedded in the unresolved internal problems of the November 1977 grab of power by the military wing in Zanu. The November putsch presents a sense of déjà vu. It continues to be about succession and the rivalries within the Shona hegemony over Zimbabwean political power which reached a crescendo after 2013, with the sequential purging of Joice Mujuru and Emmerson Mnangagwa.

The second is the consolidation of the military within the state and Zanu-PF. While it has been evident since 2000 that the military have a wholly partisan thrust, this was made blatantly obvious during the 2008 elections. This intervention has been bluntly termed the first intervention by “senior military” politicians, but was even more evident in the November 2017 coup. There has been a curious reluctance by virtually all, Zimbabwean and international players, to call the intervention a “coup”, accepting the government narrative that this was merely an operation to remove only an unpopular leader. They have called the whole exercise “Operation Restore Legacy”. This is legally dubious as various commentators have pointed out.[1]

The third is the quid pro quo by the international community for tolerating the coup, and this resides in the “new dispensation” being able to deliver free, fair and credible elections. This seemed relatively straightforward in the heady days after Robert Mugabe’s removal and the mass demonstrations by the citizens in support of his removal. However, this should not be confused as support for President ED as it was as much about the removal of Robert Mugabe as it might be of the demise of Zanu-PF as well. The street protests only happened because the military encouraged it. Zimbabweans have shown a healthy aversion to protest and demonstrations since 2000, with the consistent findings in every Afrobarometer poll since 2000 that Zimbabweans do not join others to raise an issue, or join a protest or demonstration. As RAU and MPOI have shown, Zimbabweans are “risk averse” when it comes to political participation, voting excepted (RAU & MPOI. 2017).

The upshot of all of this is the considerably higher stakes for the election in 2018 than any other election since 1980.

The Election and Its Problems

Every election since 2000 has been deeply disputed by opposition political parties, and has also resulted in disputed views in the international community. The exception was the response to the violent run-off in 2008, but it is worth pointing out that this was due to the violence and there has not been the same level of condemnation to the other polls where there were demonstrable electoral irregularities. The run up so far to the 2018 poll, and the 2013 poll before this, have not been marred by high levels of violence, which is an undoubted positive, but it is clear that a violent poll following a coup would result in a very strong international response.

Thus, the big question to be addressed in the forthcoming poll is the extent to which the process will lead to an undisputed result and that the conditions can be realistically deemed free, fair and credible. Here, a broader range of issues need to be considered than in previous elections. These must cover not only what might be termed the technical aspects of elections – the independence, transparency and accountability of the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission, the state of the voters’ roll, the printing and allocation of ballots, etc. – but also the non-partisan nature of the state and the security sector, the non-partisan nature of traditional leadership, the openness of the state media, and the adherence to the Constitution generally.

All of these issues required the government, the so-called “new dispensation”, to undertake an assertive programme of reform and, to date, there is little evidence that the government has made any credible attempt to do so. The “New Dispensation” is pushing for re-engagement with the international community under the mantra Zimbabwe open for business, if somewhat rhetorically suggesting economic reforms. This strategy seems to be working and is the basis on which engagement on the economic front is taking place with the government claiming $15 billion worth of investment pledges committed to Zimbabwe. On the political front, there is less to praise, and two simple examples illustrate this.

In 2017, and in defiance of both the Constitution and the law, the Chief’s Council openly declared their support for Robert Mugabe and Zanu-PF. This was recently challenged in the courts by the Elton Mangoma leader of the Renewal Democrats, with the High Court ruling that President of the Chief’s Council, Chief Fortune Charumbira should publicly retract his statement and that traditional leaders should comply with the Constitution.[2] Rather than publicly support the High Court ruling and demonstrate constitutionalism, the government has allowed Charumbira to appeal against the ruling. Traditional leaders have been partisan towards Zanu-PF in all elections since 2000. The importance of the traditional leaders in Zanu-PF election matrix is also evidenced by recent vehicle purchases timed to harvest support from the traditional leaders and the under them.

A related example deals with the forced attendance of school children at political rallies. Teachers and pupils have all been unwilling participants in political mobilisation fiestas in the past, with teachers having been subjected to political violence and schools even used as “militia bases” for intimidation and violence (RAU. 2018; RAU. 2012). The Amalgamated Rural Teachers Union of Zimbabwe (ARTUZ) has challenged these practices, firstly by approaching the Zimbabwe Human Rights Commission (ZHRC) and subsequently in the High Court when evidence showed that the ZHRC pronouncements were being ignored. ARTUZ was successful in both applications, but rather than government enforcing the rulings it has allowed Zanu-PF to appeal.

Neither of these examples suggests any kind of commitment to constitutionalism but rather a refusal to give up an electoral advantage. In addition, there remains the clear partisan nature of the security sector, the embedding of senior men in uniform in the executive and the state, and the constriction of the media space. This has not created any trust by the citizens in the electoral system and process as demonstrated by the findings of the recent Afrobarometer survey and subsequent analysis (Bratton & Masunungure. 2018). Citizens have low trust in the electoral commission and marked pessimism about whether their votes will be counted (29%), that the results will reflect the poll (44%), and whether the military will accept the results (41%). More worrying, and given the violence that has accompanied previous elections (and probably the role of the military), 40% expect violence after the elections. Thus, the military has become the hegemonic gatekeeper of Zimbabwe’s democratic process always ensuring that Zanu-PF will not be challenged out of power.

None of this suggests that government has created a climate of confidence; and this without dealing with all conflicts (and many court cases) between the Zimbabwe Electoral Commission (ZEC) and opposition political parties and civil society organisations. The technical aspects of the elections under the control of ZEC have led to a rancorous atmosphere, exemplified by mistrust on all sides, arrogance of the ZEC officialdom, and most seriously, a complete failure by the Commission to demonstrate openness, transparency and accountability.

The Players

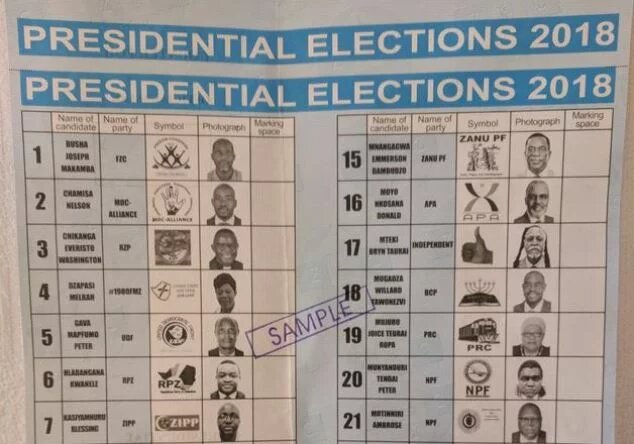

Whatever else is going on in the run-up to these elections, there is the possibility of an enormous turn out. 5.7 million Zimbabweans have registered to vote, and opinion polls suggest that around 80% say that they will actually vote. More women than men have registered – 54% to 46% - and interestingly 66% of the strictly rural constituencies have percentages of women registered greater than the average. The interest in women voting is not matched by an appreciable number of women seeking representative posts. Of the 1,592 candidates only 204 (13%) are women, and neither of the two main parties, Zanu-PF or the MDC Alliance, have more than 10% of women as their nominated candidates. After an assertive campaign by women’s organisations to get a 50/50 split (as required by the constitution), this is deeply disappointing. The electoral environment continues to reflect the patriarchal nature of politics elbowing women or making the participating environment impossible.

There has also been a marked improvement in registration by the youth compared to 2013, and especially urban youth. There is a 77% increase in urban youth registering and the ratio of rural to urban youth under 35 years has declined from 3:1 to 2:1. With a young population, and with nearly 65% of registered voters under 45 years, the youth vote will likely decide the outcome of the 2018 election. Given this demographic profile, and the fact that very few have had any experience of living under colonial rule a key emblematic of the ruling party, will this make a change or will the inevitable rural/urban divide work once again to Zanu-PF’s advantage?

Certainly, and according to reliable opinion polls, the gap between the MDC Alliance and Zanu-PF has been closing over the past year, with Zanu-PF holding a slender 12% lead over the Alliance. However, a very substantial 24-28% of citizens have not shown their allegiance and it is hard to know how this group will behave. Being “reticent” or “uncertain” is frequently interpreted to mean a reluctance to declare open support for a party other than Zanu-PF, but it is the magnitude of this group that causes discomfort to pundits. According to the data on registration, the gap between Zanu-PF and the MDC-Alliance is in the order of around 700,000 votes whilst, the “reticent” and “undecided” represent about 1.4 million at the lower level or 1.6 million at the higher level. Either way, the “reticent” and “undecided” could substantially change the result were the poll to be genuine and the turnout has high as predicted by the Afrobarometer.

It will certainly be a two-horse race for the presidency, Mnangagwa (Zanu-PF) versus Chamisa (MDC Alliance) which, given the powers of the Zimbabwean presidency, is the critical poll in respect of political power. It is highly probable that the House of Assembly may have a much more diverse complexion than ever before, with many smaller parties represented and even some independents. But for the presidential poll, the big question remains: how will all the former Zanu-PF supporters displaced due to the purges and the coup vote? Will there be a repeat of 2008 when, Zanu-PF supporters were encouraged to vote for the party on every ticket except the presidency and Robert Mugabe lost? Will the “Robert Mugabe” factor play a role in undermining Mnangagwa given that 35% of Zimbabweans, who are probably poor, still apparently trust Mugabe after his ousting? The opposition has also had its fair share of problems. How will the MDC-T split affect the vote especially in Matabeleland region? And, given all that has been canvassed above, will the poll actually be free, fair and credible, and the military genuinely have no stake or influence in the outcome?

Conclusion

The overall picture is thus not a happy one, and has led to one major demonstration by the MDC Alliance and the high probability of more to come. Most seriously for a deeply polarised and struggling citizenry is the prospect of yet another disputed poll, with the attendant problems of re-engaging the international community. The big question here is what will happen in the event of a disputed poll, and what will be the response of the international community? Having avoided the complexity of calling November 2017 a coup, but not having a free, fair and credible election, is there a plan amongst international players about how to handle this problem? How does the international community interpret the challenges ZEC is facing a few days ahead of polls? Or will the international community, closely observing the poll, follow the trend of the past and delegate everything to SADC? And will the cheap solution be yet another elite pact and another government of national unity?

References:

Bratton, M & Masunungure, E (2018), Public attitudes toward Zimbabwe’s 2018 elections: Downbeat yet hopeful? June 2018, Afrobarometer Policy Paper No.47.

Mandaza, I (2016), Introduction. in I. Mandaza, (2016) The Political Economy of the State in Zimbabwe: The rise and fall of the Securocrat State. Harare: Southern African Political Economy Series.

RAU & MPOI, Are Zimbabweans Revolting? March 2017. MPOI & RAU. [http://researchandadvocacyunit.org/system/files/Risk%20aversion%20short…]

RAU (2010), What are the options for Zimbabwe? Dealing with the obvious! Report produced by the Governance Programme. 4 May 2010. Harare: Research & Advocacy Unit.

PTUZ (2012), Political Violence and Intimidation of Zimbabwean Teachers. May 2012. Report prepared for the Progressive Teachers Union of Zimbabwe [PTUZ] by the Research and Advocacy Unit [RAU]. Harare: Progressive Teachers Union of Zimbabwe.

RAU (2018), Making schools zones of safety & peace. June 2018. Harare: Research & Advocacy Unit;

Southall, R (2013), Liberation Movements in Power: Party and State in Southern Africa. James Currey: University of Kwa-Zulu Natal Press.

[1] Big Saturday Read: Legal charade threatens new government, Alex Magaisa, 25 November 2018. [https://www.bigsr.co.uk/single-post/2017/11/25/Big-Saturday-Read-Legal-…]

[2] HIGH COURT BANS ALL TRADITIONAL LEADERS FROM POLITICS. Kubatana. net. (Source: Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights (ZLHR)17 May 2018)

[http://kubatana.net/2018/05/17/high-court-bans-traditional-leaders-poli…]

.