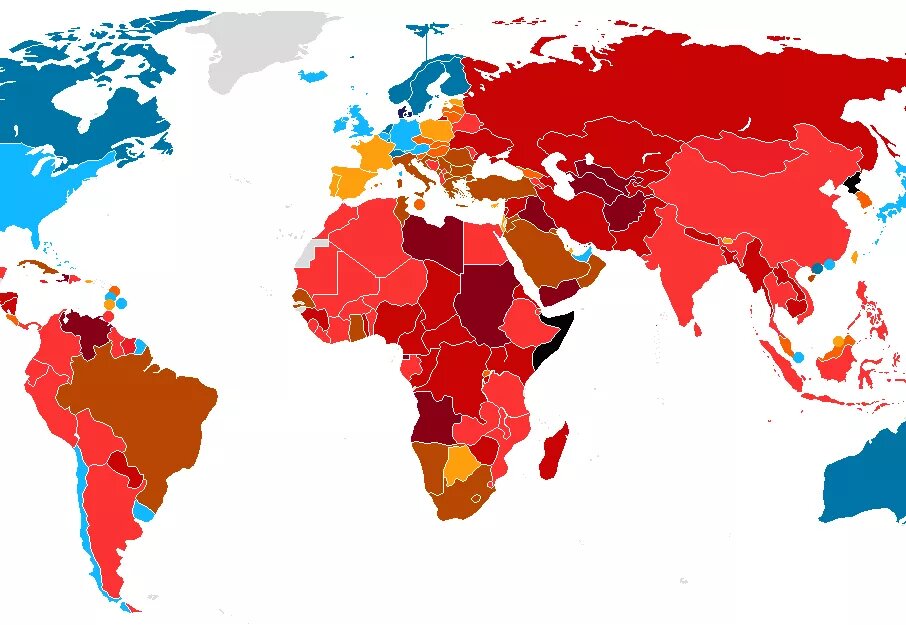

The results of Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index, released this week, hold mixed news for SA. Our ranking has improved from 67 in the 2014 survey to 61 out of 168 countries surveyed last year. Our score, at 44, has remained the same, with 100 perceived as very clean and 0 as highly corrupt. It places us in the league of corrupt nations, with nine sub-Saharan African countries scoring better or the same as us.

We are not the most corrupt country on earth, but a short way beneath us the slide becomes extremely slippery. If we hit these treacherous slopes, we won’t be able to extricate ourselves.

Take our Brics partners. With Brazil having declined from a 2014 ranking identical to SA to a 2015 score of 38 and a ranking of 76, and with India also ranked at 76, China at 83 and Russia at 119, we are, relatively speaking, the veritable good guys in this group. But do we want to go there? Does our leadership want to countenance, as in Brazil, hundreds of thousands of citizens on the streets, a credit rating cut to junk and a thoroughly discredited polity and reviled public and private sectors?

But none of this should detract from the glimmer of good news: perceptions of corruption in SA are stable, and this is for the second consecutive year.

On the face of it, these results contrast markedly with those of the Global Corruption Barometer, another well-regarded Transparency report, released in December last year. That survey reported that 83% of South Africans surveyed believe corruption is getting worse (higher than any of the other sub-Saharan African countries surveyed) and that 79% of those surveyed thought the government was doing a poor job of tackling corruption.

How do we reconcile the apparently divergent results of these two important surveys, conducted in the same period? The perceptions index is a composite generated from various surveys conducted over the course of the year by groupings such as the World Bank, the African Development Bank and the Economist Intelligence Unit. Those surveyed are "experts", generally academics and consultants, business people and public officials.

The "experts" perceive that in SA there is, at high levels of government and in the ruling party, a notable surge in concern at escalating corruption. They see important high-level anticorruption reforms being introduced by key institutions such as the Treasury. They also see citizens marching in the streets and civil society organisations litigating, usually successfully, in the courts. This all generates the perception, on the part of the elite who are surveyed, that at last something is being done.

It is a valid perception that squares with our experience — a range of government institutions from the Gauteng education department to the Treasury and other national government departments evince a new willingness to take on corruption, even to work with us in doing so.

While this does not represent our total experience, we too believe "something is being done", that those in power are finally persuaded that their personal credibility and that of the institutions they lead demand that they be seen to be tackling corruption.

The barometer reports the outcome of a survey conducted among a representative sample of "ordinary" citizens. These South Africans see headline-making issues such as Nkandla, they see numerous examples of those with political power and wealth getting away with corruption on a grand scale, not only on the national stage, but also by their representatives in the provinces and in local government and local business interests. In their taxis and housing allocation queues, they experience corruption daily.

Their perceptions are equally valid and also square with our experience. There is great impunity at the top end of the food chain, be it at the top of the country or at the top of a province or town or at the top of a company brazenly bribing its powerful counterparts in these various tiers of government. So-called "petty" corruption is rife and is a form of corruption particularly injurious to poor communities.

The upshot is that the efforts to combat corruption by some in positions of power and influence are not arresting growing levels of distrust in government and politics on the part of those at the bottom, because these efforts are overshadowed by their brazenly corrupt colleagues at the top as well as by those who possess power over the everyday lives of ordinary citizens. This is why it is correct to see a glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel, but to simultaneously insist that we have a long way to go and that a positive outcome is not certain.

The solutions are clear, albeit extremely challenging. If you are an anticorruption reformer at the top — probably a reader of Business Day — look at those on either side of you at your Cabinet and boardroom tables — and indeed, those at the very head of these tables. That is where you are likely to find your most damaging and powerful opponents. If you cannot demonstrate that you have the authority and the courage to tackle those with power who display their brazen impunity daily, don’t expect renewed public trust when you release a new policy paper or arrest a hapless official in a provincial housing department.

Zero in on those causing the greatest pain and suffering to ordinary residents — the teachers who demand sexual favours in exchange for marks, the security guards who abuse refugees at home affairs offices, the housing official who demands a bribe.

Taking on petty corruption in thousands of government offices is daunting. But both tasks — tackling impunity at the top and petty corruption at the bottom — can be short-circuited by targeting the law enforcement officials who condone or participate in corruption. In the criminal justice institutions too, corruption goes to the very top.

This is not surprising — you can bet that when those with political and economic power have reason to fear the actions of an independent policing and prosecutorial power, those will be the institutions that will be the most comprehensively corrupted.

Don’t take refuge in the hoary old canard that insists these surveys measure perceptions rather than "reality". There is no other way to measure a collective aggregate of criminal conspiracies in which both parties face potential criminal liability. In these circumstances, any measure of reported or prosecuted corruption is bound to hugely understate the problem.

Besides which, perceptions are powerful drivers of action. The public (including the elite) perceive public and private sector institutions and leaders to be untrustworthy. This is largely explained by their perceived complicity in corruption. They take their grievances to the streets or withhold investment. The only way to shift these perceptions is to tackle the underlying problem. And that is rampant corruption, not those who bring the bad news.

This article was first published in Business Day. Lewis is executive director of Corruption Watch, a partner organisation of HBS Southern Africa.