In the early 2000's a series of 'targeted measures' were introduced by the EU, US, and later Australia, New Zealand and Canada, against the movement and assets of particular individuals in the Mugabe regime. The measures were introduced as a response to serious electoral irregularities and human rights abuses in the Parliamentary and Presidential elections in 2000 and 2002 respectively. It was also clear that these interventions were a response to the state-led land acquisition process that unfolded for much of the 2000's, which radically transformed the property ownership structure on the land in favour of small scale farming.

The contestation over the meaning of the 'targeted measures' has marked the political discourse in the country from the early years of the new millennium until the present. For the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), the civic movement and Western countries these measures were a just response to the repressive and authoritarian politics of the Mugabe regime and the violence and irregularities that marred most of the plebiscites in the decade of the 2000's. During this period the measures played an important role in keeping a focus on the abuses of the Mugabe state, and provided some measure of accountability for the gross violations of human rights carried out by the state in this period.

For Zanu PF the measures were not targeted but amounted to a broader regime of sanctions that affected not only particular individuals in the ruling party but the economy and the Zimbabwean populace more generally. This argument was based on the fact that these punitive measures from the West not only restricted the supply of military equipment to the Mugabe government but, aside from the provision of humanitarian assistance, prevented any substantive new investments from entering the country. Moreover as the terms of the US Zimbabwe Democracy and Recovery Act 2001 set out, the US opposed any new loan, credit facilities or debt reduction initiatives being carried out by the International Financial Institutions. These measures effectively added to the investment pressures that had built up in Zimbabwe since the Zimbabwean Government's fall out with the International Financial Institutions in the late 1990's.

Throughout the period of the Zimbabwean Crisis in the 2000's the Mugabe regime incorporated the sanctions issue into its anti-imperialist and Pan Africanist discourse, and made it a key component of the 'patriotic history' through which it crafted its political project. This strategy worked effectively in mobilising the support of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the African Union (AU). It was also effective in casting the opposition as part of a Western intervention strategy in Zimbabwe designed to undermine the sovereignty of the country and the goals of the liberation struggle.

Thus, by the time of the signing of the SADC facilitated Global Political Agreement (GPA) between Zanu PF and the two MDC's in 2008, Zanu PF's rhetoric on the sanctions issue had already found considerable resonance in the Southern African region and the African continent, where the deployment of Mugabe's anti-imperialist position gained effective political traction.

Article IV of the GPA committed parties to the lifting of all forms of measures and sanctions against Zimbabwe, and to a re-engagement with the international community. This agreement gave even greater credence to the Zanu PF position on sanctions and forced the MDCs to publically renounce any further commitment to these measures, notwithstanding the ambiguous position that Tsvangirai's MDC in particular was taking on this issue behind closed doors. Moreover once the GPA was signed, with the position on sanctions repeatedly endorsed by SADC at various summits thereafter, the persistence of these measures by the West became increasingly counter-productive and placed the MDCs in a permanently defensive position on this issue.

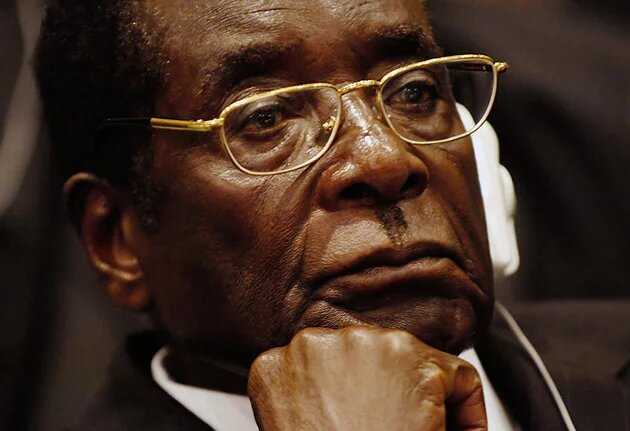

In response to the GPA the EU began a process of gradually moving away from the 'targeted measures' and at different stages removed various Zanu PF figures and entities from the punitive list. This process continued until after the July 2013 elections, when the EU removed all names from the targeted list except Mugabe and his wife, with the restrictions on military cooperation also remaining in place. While the EU maintained that there were serious problems with the elections, a combination of the overwhelming election 'loss' by the MDC, Belgium's interests in Zimbabwe's diamonds, and increasing divisions over the Zimbabwe question, pushed the organisation into a continuing rapprochement with Zimbabwe. It is fair to predict that when the EU meet on the Zimbabwe issue in November 2014, the remainder of the sanctions are likely to be removed, barring any new round of serious human rights abuses by the Zimbabwe government.

The US on the other hand have retained their position on the sanctions maintaining that the serious irregularities in the 2013 elections have provided no incentive to change its stance. In truth the US is able to maintain its tough posture on Zimbabwe because, in the calculation of global US interests, Zimbabwe represents an issue of little significance. Therefore the US loses very little through its current stand.

In the meantime the Mugabe government has continued to use its 'Look East' policy with China in particular to bargain in its re-engagement strategy with the West. As the Zimbabwean economy continues to face serious challenges in the post-election period, the need for new investments, beyond the interventions of the Chinese in selected sectors such as mineral resources and agricultural sub-contracting, remains urgent. This is particularly the case in the massively de-industrialised manufacturing sector. The current 'anti-corruption' drive of the Mugabe government may not only be related to the succession battle within the ruling party, but may also be an indicator of its need to present a reform face to the West. There are still many contradictory signals coming out of the Zimbabwean government, not the least of which is the confusion over its Indigenisation Policy. Nevertheless at the moment the movement towards a more comprehensive re-engagement between the EU and Zimbabwe appears to be on course.

In conclusion it is clear that whatever the merits of the sanctions up to the mid 2000's, once the GPA was signed they became counter-productive. In the face of the agreed GPA position on the removal of sanctions and the SADC and AU opposition to the measures, the continued Western insistence on the latter gave the appearance of yet another example of Western arrogance towards an African initiative. In the new political context of the post 2013 election, continuation of the sanctions serves little purpose besides bolstering continental support for the Mugabe regime and exposing the ambiguity of the MDC-T and the civic movement on this issue. It is time for these measures to be removed.

Brian Raftopoulos is the director of research at Solidarity Peace Trust.