Sometimes, novelist Sonwabiso Ngcowa observes, a narrative form can tell you more. More, he means, than statistics, analysis and the dispassionate gaze that generates even the most accurate impressions of a time or a society.

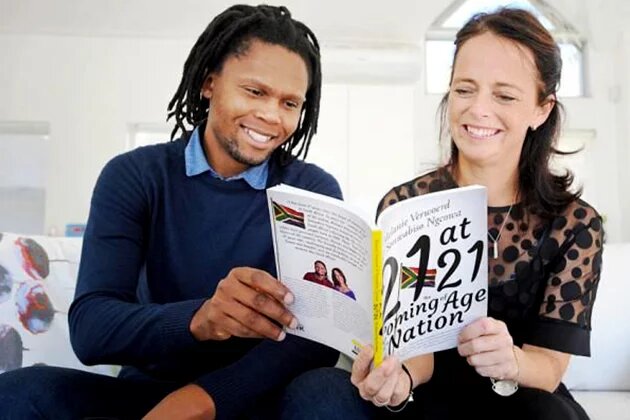

And in this case, he is speaking particularly about his collaboration, at her invitation, with Melanie Verwoerd on the book, 21 at 21, The Coming of Age of a Nation.

Both authors are present in the narratives assembled in the book, based on interviews with 22 subjects born in 1994, but in deliberately slight form so that, as Verwoerd puts it, “we could give young people a voice”.

The result is arresting.

At times harrowing and alarming, yet inspiring, too, (even if, here and there, shot through with often charming instances of naivete or sentimentality), 21 at 21, The Coming of Age of a Nation has the effect of brushing aside the habitual rhetoric of liberation nostalgia, and confronting us with the condition of our future. In this, the hard-nosed realism of its register is conceivably its most redemptive quality.

The book seeks neither to put a “June 16” gloss on life in 2015, as democratic South Africa marks its own 21st, nor to call into question the country’s historical trajectory from apartheid to democracy. Instead, it challenges the complacency and assumed optimism – or, indeed, pessimism – of a society failing to pay enough attention to itself.

The idea of the book was Verwoerd’s. Her engagement with the democratic journey in South Africa began at its inception when, at 27, she became the youngest female MP to enter Parliament by taking her seat in the ANC benches in 1994. Her marriage to her now ex-husband, Wilhelm, the grandson of Hendrik Verwoerd, considered the architect of so-called “Grand Apartheid”, earned her much attention, chiefly as the embodiment of the new non-racial optimism of the Mandela years. After a spell abroad as ambassador in Dublin, and head of Unicef in Ireland, she returned home with undimmed interest in the now 21-year-old project of which she was a part.

What, was the essential question, does the future look like?

After attending the launch of Ngcowa’s first novel, In Search of Happiness, Verwoerd sought him out as a collaborator, and the result, made possible by the support of the Heinrich Böll Foundation, is a book of the stories, thoughts and dreams of young South Africans.

Among its 22 subjects are widely divergent voices; the student from Orania who speaks of “our generation” and means not whites, not Afrikaners, not conservatives, but all young people who have a common if complicated interest; the well-spoken former private school pupil who lives an alienated life as a transgender person in a shelter made of plastic sheets under a city bridge, earning a living of sorts by selling her body, but dreaming of being an ordinary, loved housewife; the Diepsloot twins who play strings in an orchestra and perceive a future of achievable dreams; the young woman who grew up in a home of 18 children, was abandoned by her mother at 3, later fatally stabbed an older woman, and who confesses in a whisper, “happiness does not walk with me”; the brave if constantly frightened Khayelitsha lesbian; the sassy, go-getting fashion designer from Motherwell; and the son of escapees from the Rwandan genocide whose South African story is a bittersweet one.

If it’s a sampling of contrasts and very different lives, the authors were struck by common threads.

In their introduction, they highlight some troubling truths. Among them is the pervasive disruption of family life (with only five of all the young people interviewed having a stable family life) and “either the complete absence or the destructive presence of father figures in the children’s lives”, with most citing domestic violence as unexceptional. Virtually all were victims of the “struggle for education”, incorporating inadequate schooling and lack of support to continue studying. They also found a profound absence of “vision” among most of the young people, in the sense of their not having or knowing how to craft definite plans to reach their dreams.

One of the authors’ objectives was to seek “in some small way (to) break down stereotypes and preconceived ideas about young people”.

And these young people were not, as the stereotype might have it, obsessed with material trappings, but more so with such things as caring for their families or having a stable job.

Though few showed any interest in formal politics (“Many expressed negative opinions about the current leadership, but were vague and often factually inaccurate when asked about the reasoning behind their opinions.”), all had an unhesitating sense of their own, often complex, identity as South Africans.

And, they conclude, “despite the pain and many challenges (they) have faced and continue to endure, they still have faith that their lives will be better in the future”.

“Their strength, resilience and determination had us in awe and gave us a sense of hope for the next 21 years of our democracy.”

That said, when they began their project, “we had sincerely hoped life had become easier for those who were born at the dawn of our democracy”.

“However, for many of the youths we spoke to, this has not been the case.”

Verwoerd said: “That’s not what we wanted in 1994 when we went into Parliament; we should not see 21-year-olds now battling against the system, against the lack of education – not because they did not go to school, but because schools are not good enough.

“Decision-makers must start paying attention, because they aren’t paying attention, they really aren’t. This is the first generation coming of age, the ones who must take over, and they are not doing well, they are coping, but against the odds and that’s just not good enough. It’s not where we were supposed to be 21 years on.”

Ngcowa said – and Verwoerd agreed – that he had not anticipated his own new levels of understanding the country through listening to its young people and recording their stories.

And, for readers, he said, “this is an invitation to feel more South African, being more familiar with who actually lives here and what people go through”.

Verwoerd remembered being “caught unawares” by the reality of the lives of their subjects, and their amazement that, for once, “someone was listening to them”.

“It touches you when you realise that in the battle for survival, there is often just not time for them to be heard. And for me, I hope the book will help people to look on our young people with a more gentle, less judgmental eye. This is a mirror we need to look at, this is our society.

“Even the lack of a father figure, which is true for many on a personal level, is true for all of us on a collective level, where as a country we are looking for leadership in strong male figures which don’t seem to be there.”

The book begins, as this story must end, on an immensely poignant note. The first interview in 21 at 21, The Coming of Age of a Nation is with Jenna Lowe, who turned her own extraordinary battle with a rare and incurable lung disease into a campaign to help others. A brief footnote at the end of the chapter on Lowe reads: “At the time of going to print, Jenna was making a full recovery.” Tragically, Lowe died this week after a complication associated with her otherwise successful lung transplant.

With this knowledge, it is at once heart-breaking and inspiring to read how, when Verwoerd asked her if, looking back on her life, she had any regrets, Lowe “looks across at me and says, ‘I don’t have any real regrets. Well, very few. In retrospect, I wish that I had complained a bit earlier when I started to feel unwell. And maybe I regret a little that I was always so future orientated. Unlike other kids, I did not live in the moment. I would even save my Easter eggs for months. I was so much happier with tomorrows than todays. I wish I could have changed that a little bit.’”

But it wasn’t in her nature, this brave girl who looked forward to her life.

And it could be – just as Verwoerd and Ngcowa brim with an almost unaccountable, celebratory confidence in the sheer resilience of the subjects of their remarkable narrative – that Jenna’s courageous if not unrueful levelling with her fate is a testament to young South Africa’s resolve.

These are not, one comes away feeling, people to be trifled with; they are making a go of it, but deserve, and know they deserve, so much more.

*This article was originally published in the Weekend Argus on the 13th of June 2015 and can be viewed online via:

http://www.iol.co.za/news/trapped-in-a-world-they-never-made-1.1872029#.VYFPuFfYs7k